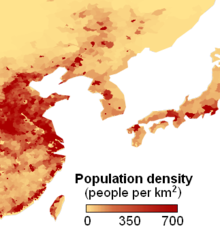

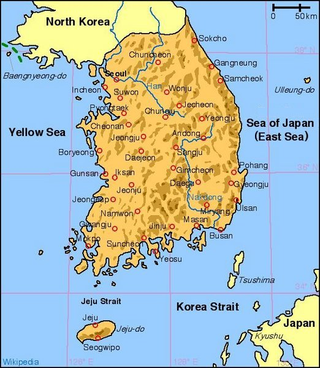

South Korea is located in East Asia, on the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula located out from the far east of the Asian landmass. The only country that shares a land border with South Korea is North Korea, lying to the north with 238 kilometres (148 mi) of the border running along the Korean Demilitarized Zone. South Korea is mostly surrounded by water and has 2,413 kilometres (1,499 mi) of coast line along three seas; to the west is the Yellow Sea, to the south is the East China Sea, and to the east is the Sea of Japan. Geographically, South Korea's landmass is approximately 100,364 square kilometres (38,751 sq mi). 290 square kilometres (110 sq mi) of South Korea are occupied by water. The approximate coordinates are 37° North, 128° East.

The Yellow River is the second-longest river in China and the sixth-longest river system on Earth, with an estimated length of 5,464 km (3,395 mi) and a watershed of 795,000 km2 (307,000 sq mi). Beginning in the Bayan Har Mountains, the river flows generally eastwards before entering the 1,500 km (930 mi) long Ordos Loop, which runs northeast at Gansu through the Ordos Plateau and turns east in Inner Mongolia. The river then turns sharply southwards to form the border between Shanxi and Shaanxi, turns eastwards at its confluence with the Wei River, and flows across the North China Plain before emptying into the Bohai Sea. The river is named for the yellow color of its water, which comes from the large amount of sediment discharged into the water as the river flows through the Loess Plateau.

The Sea of Japan(see below for other names) is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it has almost no tides due to its nearly complete enclosure from the Pacific Ocean. This isolation also affects faunal diversity and salinity, both of which are lower than in the open ocean. The sea has no large islands, bays or capes. Its water balance is mostly determined by the inflow and outflow through the straits connecting it to the neighboring seas and the Pacific Ocean. Few rivers discharge into the sea and their total contribution to the water exchange is within 1%.

The Bay of Fundy is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its tidal range is the highest in the world. The name is probably a corruption of the French word fendu, meaning 'split'.

Bohai Bay is one of the three major bays of the Bohai Sea, the northwestern and innermost gulf of the Yellow Sea. It is bounded by the coastlines of eastern Hebei province, Tianjin municipality and northern Shandong province south of the Daqing River estuary and north of the Yellow River estuary. It is the most southerly water in the northern hemisphere where sea ice can form.

Mudflats or mud flats, also known as tidal flats or, in Ireland, slob or slobs, are coastal wetlands that form in intertidal areas where sediments have been deposited by tides or rivers. A global analysis published in 2019 suggested that tidal flat ecosystems are as extensive globally as mangroves, covering at least 127,921 km2 (49,391 sq mi) of the Earth's surface. They are found in sheltered areas such as bays, bayous, lagoons, and estuaries; they are also seen in freshwater lakes and salty lakes alike, wherein many rivers and creeks end. Mudflats may be viewed geologically as exposed layers of bay mud, resulting from deposition of estuarine silts, clays and aquatic animal detritus. Most of the sediment within a mudflat is within the intertidal zone, and thus the flat is submerged and exposed approximately twice daily.

The Leizhou Peninsula, alternately romanized as the Luichow Peninsula, is a peninsula in the southernmost part of Guangdong province in South China. As of 2015, the population of the peninsula was 5,694,245. The largest city by population and area on the peninsula is Zhanjiang.

Pulicat Lake is the second largest brackish water lagoon in India,, measuring 759 square kilometres (293 sq mi). A major part of the lagoon lies in the Tirupati district of Andhra Pradesh. The lagoon is one of three important wetlands that attracts northeast monsoon rain clouds during the October to December season. The lagoon comprises the following regions: Pulicat Lake, Marshy/Wetland Land Region (AP), Venadu Reserve Forest (AP), and Pernadu Reserve Forest (AP). The lagoon was cut across in the middle by the Sriharikota Link Road, which divided the water body into lagoon and marshy land. The lagoon encompasses the Pulicat Lake Bird Sanctuary. The barrier island of Sriharikota separates the lagoon from the Bay of Bengal and is home to the Indian Space Research Organisation's Satish Dhawan Space Centre.

Foxe Basin is a shallow oceanic basin north of Hudson Bay, in Nunavut, Canada, located between Baffin Island and the Melville Peninsula. For most of the year, it is blocked by sea ice and drift ice made up of multiple ice floes.

The spoon-billed sandpiper is a small wader which breeds on the coasts of the Bering Sea and winters in Southeast Asia. This species is highly threatened, and it is said that since the 1970s the breeding population has decreased significantly. By 2000, the estimated breeding population of the species was 350–500.

Saemangeum is an estuarine tidal flat on the coast of the Yellow Sea in South Korea. It was dammed by the government of South Korea's Saemangeum Seawall Project, completed in 2006, after a long fight between the government and environmental activists, and is scheduled to be converted into either agricultural or industrial land. Prior to 2010, it had played an important role as a habitat for migratory birds.

The Saemangeum Seawall, on the south-west coast of the Korean peninsula, is the world's longest man-made dyke, measuring 33 kilometres (21 mi). It runs between two headlands, and separates the Yellow Sea and the former Saemangeum estuary.

The Salish Sea is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean located in the Canadian province of British Columbia and the U.S. state of Washington. It includes the Strait of Georgia, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Puget Sound, and an intricate network of connecting channels and adjoining waterways.

The East Asian–Australasian Flyway is one of the world's great flyways of migratory birds. At its northernmost it stretches eastwards from the Taimyr Peninsula in Russia to Alaska. Its southern end encompasses Australia and New Zealand. Between these extremes the flyway covers much of eastern Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, South-East Asia and the western Pacific. The EAAF is home to over 50 million migratory water birds from over 250 different populations, including 32 globally threatened species and 19 near threatened species. It is especially important for the millions of migratory waders or shorebirds that breed in northern Asia and Alaska and spend the non-breeding season in South-East Asia and Australasia.

China's vast and diverse landscape is home to a profound variety and abundance of wildlife. As of one of 17 megadiverse countries in the world, China has, according to one measure, 7,516 species of vertebrates including 4,936 fish, 1,269 bird, 562 mammal, 403 reptile and 346 amphibian species. In terms of the number of species, China ranks third in the world in mammals, eighth in birds, seventh in reptiles and seventh in amphibians.

China’s coastline covers approximately 14,500 km from the Bohai gulf in the north to the Gulf of Tonkin in the south. Most of the northern half is low lying, although some of the mountains and hills of Northeast China and the Shandong Peninsula extend to the coast. The southern half is more irregular. In Zhejiang and Fujian provinces, for example, much of the coast is rocky and steep. South of this area the coast becomes less rugged: Low mountains and hills extend more gradually to the coast, and small river deltas are common.

China has one-fifth of the world's population and accounts for one-third of the world's reported fish production as well as two-thirds of the world's reported aquaculture production. It is also a major importer of seafood and the country's seafood market is estimated to grow to a market size worth US$53.5 Billion by 2027.

The Iceland Sea, a relatively small body of water, is bounded by Iceland. It is characterized by its proximity to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which transforms into the Kolbeinsey Ridge, and the Greenland-Scotland Ridge, and it lies just south of the Arctic Circle. This region is typically delineated by Greenland to the west, the Denmark Strait, and the continental shelf break south of Iceland to the south. Next in the boundary line are Jan Mayen, being a small Norwegian volcanic island, and the Jan Mayen Fracture Zone to the north, with the Jan Mayen Ridge to the east of the sea. This ridge serves as the northern boundary of the Iceland Sea, acting as the dividing line from the Greenland Sea. To the immediate south of Jan Mayen, the Iceland-Jan Mayen Ridge stretches towards the Iceland-Faroe Ridge, creating a boundary between the Iceland Sea and the Norwegian Sea to the east.

The Bohai Sea saline meadow ecoregion covers the coastal deltas of the Yellow River and the Luan River where they enter the Bohai Sea in China. The saline meadows and intertidal mudflats provide an important stopping-over point for birds migrating on the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. The region is under heavy ecological pressure from human development.

The Yellow River Delta National Nature Reserve (YRDNNR) is a protected area in the city of Dongying, China, which covers wetland habitats on the shore of the Bohai Sea. These wetlands are formed through the deposition of silt by the Yellow River, forming a large and growing delta. The reserve is split geographically into two portions, one covering the current mouth of the Yellow River and one covering wetlands that remain near a former river mouth. In management terms, it is divided into a core area with a high level of protection, and buffer and experimental zones which allow for greater human activity.