Christopher Columbus, on his first Spanish-sponsored voyage to the Americas in 1492, sailed south from what is now the Bahamas to explore the northeast coast of Cuba and the northern coast of Hispaniola. Columbus, who was searching for a route to India, believed Cuba to be a peninsula of the Asian mainland. [1] [2] The first sighting of a Spanish ship approaching Cuba was on 28 October 1492, probably at Bariay, Holguín Province, on the eastern point of Cuba. [3]

During a second voyage in 1494, Columbus passed along the south coast of the island, landing at various inlets including what was to become Guantánamo Bay. With the Papal Bull of 1493, Pope Alexander VI commanded Spain to conquer, colonize and convert the pagans of the New World to Catholicism. [4]

In 1992, Cuba declared itself a secular state and permitted Catholics and others to join the Communist Party. However, religious schools have remained closed since the early 1960s.

Historically, the foundations of the Catholic Church in Cuba were considered weaker than in the rest of Latin America. Spanish colonial authorities neglected Cuba and the local church served as "a colonial backwater dumping ground for miscreant clerics". [5] The church also struggled with anti-clericalism in Cuba, further encouraged by the growth of Freemason circles and Protestant churches, many of them of anti-Catholic outlook. [5] The role of the Catholic Church recovered in the late 16th century - the church became the main agency of welfare and education on the island, attempted to mediate conflicts, offered priesthood as a possibility for socioeconomic mobility to poor Cubans, and contributed towards founding Cuban national identity; many Catholic priests played an important role in the Cuban independence movement, such as Félix Varela. [5] The peak of the Cuban Catholic Church as a social force was in the 1920s and 1930s, and many Catholic organisations and movements were established in that period, such as the la Juventud Cubana in 1927, Acciön Catölica in 1928, Caballeros Catölicos in 1929 and Agrupaciön Catölica Universitaria in 1931. As political parties of Marxist outlook and labour unions became common in the Cuban society, the Church established competing parties and trade unions to promote Catholic social doctrine instead. [5]

As Fulgencio Batista came to power in Cuba through his 1952 coup, the response of the Catholic Church was negative, as "many religious leaders had judged the regime of Fulgencio Batista as unconstitutional, and were sick of finding bullet-ridden bodies in the streets". [6] The church focused on evangelizing and assisting the rural population and urban lower classes, while also making humanitarian interventions on behalf of Batista's political opponents. [5] The most famous instance of the church's intervention was the intercession of Enrique Pérez Serantes on behalf of Fidel Castro, following his failed attack on the Moncada barracks in 1953. Serantes made a public appeal to spare Castro and other perpetrators, and to give them as lenient sentences possible. [6] According to Philip Rulon, this "was interpreted to mean that the majority church was sympathetic to the revolutionary movement" by the Cubans. [6]

As the insurrection against Batista's regime escalated, the church attempted to mediate the conflict. [5] Cuban cardinal Manuel Arteaga y Betancourt proposed a peace plan in 1956, ignored by the insurrectionists and the Batista regime alike. Afterwards the church hierarchy assumed an ambiguously pro-rebel stance, urging them to minimize violence while also criticizing Batista for his suppression of democracy. Cuban Catholics vigorously participated in the 26th of July Movement; many clerics and Catholic youth organised strikes and demonstrations, while also raising money for the insurrection. Members of Catholic social movements often joined the rebels, such as Manuel Artime. Already in 1956, as many as eleven chaplains were amongst anti-Batista rebels in the Oriente mountains. Priests who were part of the revolutionary movement wore "fatigue-green clerical apparel and accompanied the revolutionary band on as many of their missions as possible". [6] Many of the revolutionary priests were Basque refugees from Spain, already "accustomed to political turmoil". [6] The presence of Catholic clergy amongst the rebels provided a more moderate image of the rebels to the general population, as Castro countered the allegations of being a communist "by asserting that all the leader's men were good Catholics, and he even had several priests counted his forces". [6] In addition, other Catholic priests indirectly assisted the rebels, requesting their parishioners to donate to the revolutionary movement, while also often serving as "recruiting officers". [6] Both Batista and Castro acknowledged the contribution of the church towards the eventual revolution; Batista commented that he resigned "because of the opposition of the hacendados, colonos, the army and the church". [5] Meanwhile, Castro declared that Cuban Catholics had given the revolution "very substantial assistance". [5]

After the 1959 revolution, Cuba officially embraced atheism. Practicing Catholics and other believers were viewed with suspicion and discriminated against. Fidel Castro succeeded in reducing the Church's ability to work by deporting the archbishop and 150 Spanish priests, discriminating against Catholics in public life and education and refusing to accept them as members of the Communist Party of Cuba. [7] The subsequent flight of 300,000 people from the island also helped to diminish the Church there. [7]

As the revolutionary regime came to power in January 1959, it enjoyed popular support and produced both revolutionary and nationalist sentiment. [8] Following the revolution, the new regime was supported by the clergy, even if the degree varied. Enrique Pérez Serantes , the Archbishop of Santiago, called Castro an "exceptionally gifted man" and welcomed the new regime, while a progressive Franciscan magazine La Quincena celebrated the success of the revolution. [8] At the same time, the church tried to discourage the revolutionary leaders from any affiliation with the Soviet Union. Over twenty letters were written by Cuban bishops between 1959 and 1961, urging the Castro regime to embrace a "Catholic form of socialism". [8] Catholic magazines condemned Soviet communism as 'atheistic' while promoting papal criticism of capitalism, individualism and materialism, portraying Catholic social doctrine as a "third way" between the two opposing factions of the Cold War. A February 1959 issue of La Quincena was critical of the Cuban Communist Party, but praised the "social thought" of Castro and the leaders of the 26th July Movement. [8] The magazine warned that the Communist Party was infiltrating worker unions and syndicates, such as the CTC. Even conservative Catholic newspapers such as Diario de la Marina cautiously embraced the revolution, praising "honest administration, and healthy and appropriate nationalism" of the revolutionary regime and declaring their support for it as long as it respected "Christian values" and acted within the boundaries of the Constitution of 1940. [8]

As Fidel Castro visited the United States in April 1959, he reassured Vice President Richard Nixon that he was not a communist and only wished to pursue moderate reforms. Despite that, the Agrarian Reform Law was very extensive in scope, limiting land ownership to 1000 acres and nationalising larger holdings, which were later reorganised into state cooperatives. [8] Nevertheless, the Bishop of Havana Evelio Díaz-Cía endorsed the reform as aligned with the Catholic teachings of social justice, while bishop Alberto Martín y Villaverde urged the government to "exercise a special preference on behalf of the rural peasants" in the reform, while describing the pre-revolutionary inequality of property and wealth in Cuba as a "grave evil". [8]

Despite the initial support of the revolution, tensions started emerging between the new regime and the Catholic Church in late 1959. As the regime consolidated its power and took control of mass organisations, a break with both the United States and the Catholic Church in favour of a political realignment seemed inevitable. [8] Despite previously supporting the land reform, Enrique Pérez Serantes now expressed concerns that it was going too far and pressured the regime to carry out a reform "in harmony with interested parties" instead. The climax of tensions between Castro and the clergy was marked by the National Catholic Congress on 30 November 1959. [8] [9] During the congress, the attendees carried pictures of Our Lady of Charity, seen as "a quintessential symbol of Cuban identity". [8] [10] Bishops present asked Castro to let Catholicism provide "guiding ethical and moral values for the revolution", while José Ignacio Lazaga, the leader of the Catholic Youth Movement, said: "We believe that Catholic thinking on this subject can be summed up in this phrase: totalitarian states, no: social justice, yes." Fidel Castro denounced the Congress, accusing it of being a facade for attacks on the revolution. [8] [9]

The clergy was emboldened by the large turnout of the congress. Pérez Serantes considered it proof of Cubans being "Catholic people in the immense majority", although the large attendance could have also been caused by popular political anxiety about the direction of the revolution, in addition to support for Catholicism. [8] Castro started harshly criticising the clergy, denouncing the clerical elite as "ambitious, egotistical, retrograde and predatory". The ideological clash between the Catholic Church and the revolutionary regime was particularly visible among the youth, where Catholic and Communist youth organisations strongly competed with each other. First violent confontations between the revolutionary regime and the Catholic Church took place in July 1960, wounding several people, including a priest. In response, Bishop Eduardo Boza-Masvidal publicly attacked the regime for persecution of Catholics. [8] However, Catholic newspapers remained relatively friendly, and La Quincena stated that Catholics of Cuba must upkeep the Christian elements within the revolution, praising it as "the first revolution that was inspired by Christian motives". [8]

In August 1960, Fidel Castro denounced the Catholic Church for "systematic provocations" against the government, and further repressions followed. By September of the same year, all Catholic-aligned radio and televisions programmes had been shut down, and revolutionary militia took over Catholic seminaries, schools and several churches in January 1961. [8] The year of 1961 was marked by harshest suppression, as the Cuban government sought Soviet assistance against a possible attack from the USA. As the relations with the United States deteriorated and Soviet influence steadily increased, Castro's conflict with the Catholic Church happened amongst the sovietization of the Cuban revolution and other concessions to the Soviet Union, such as the legalisation of the Communist Party and expulsion of the American embassy's personnel in January 1961. [8] [11] In March 1961, Castro called the church "the fifth column of counterrevolution" and threatened to expel all Spanish priests from Cuba. Following the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April, the government closed all churches and detained most of the Catholic priests and bishops. Catholic colleges were nationalised, and religious orders were systematically expelled, with Jesuits and Carmelites being expelled in June. [8] Final climax of the conflict took place in September 1961, as the military opened fire on a Catholic ceremony on 10 September, killing a Catholic youth member Arnaldo Socorro Sánchez. [8] [12] On the 1st of December, Fidel Castro declared that the official ideology of Cuba would be Marxism-Leninism, therefore embracing state atheism. [8]

Following the crackdown on the church in 1961, a massive exodus of both the clergy and laymen followed, with as much as 70 percent of Catholic priests and 90 percent of Catholic laypersons eventually emigrating from Cuba. The departure was encouraged by both the international community and the American Catholic Church. The exodus not only greatly diminished the church's presence on the island, but also inflamed tensions between those who emigrated and those who stayed. [5] The remaining Catholics felt abandoned and left alone to deal with an increasingly hostile regime, while the emigrees often accused those who stayed of being collaborators. [5] The remnant of the Catholic Church on Cuba withdrew from many sectors of operation such as education and healthcare, and turned into "a shelter, conserving the familiar, and shutting out the pervasive change". [5] Catholics were discriminated in schools and in the workplace, and continued to be persecuted for "counterrevolutionary authorities", although no explicitly anti-religious campaign was mounted. [5]

The church steered clear of any conflict with the revolutionary government, and advised the remaining Cuban bishops to avoid any possible tensions. In 1961, Pope John XXIII sent Cesare Zacchi as a papal representative to Cuba, and attempted to reestablish relations with the local government. The government allowed Pope's Pacem in terris to be published in Cuba, and in 1963, the clergy was allowed to hold a requiem mass for the deceased pope in the Havana Cathedral. Afterwards, some Cuban priests started returning, while new clerics from countries such as France and Belgium also arrived in Cuba. [5] The government persecution gradually diminished in mid-1960s, and the church focused on internal reforms. The church was to become "the vanguard of the for justice worldwide", and the local clergy promoted positive aspects of the Cuban Revolution. By late 1960s, the relations between the church and the government improved enough to allow for dialogue. The leader of Acciön Catölica, Mateo Jover, observed that now every Catholic who "has a certain cultural level, practices some professional activity, and is scrupulously zealous in performing his work duties... is not only tolerated but respected." [5]

The pastoral letters of Cuban bishops from 1969 condemned the United States embargo against Cuba, urged Catholics to cooperate with the government on the matter of common good, and assured that "cooperation with Marxists for the betterment of Cuban society was legitimate". [5] These letters served to reinsert the church into the Cuban political system, reform the church along the developments of the Second Vatican Council, answer the growing progressive trends, legitimatise Christian socialism and promote ecumenical dialogue. However, the church never reestablished itself beyond its now marginalised position, as the clergy focused on improving relations with the government rather than rebuilding Catholic influence on politics and society. Nevertheless, the advances of progressive Catholics did challenge the Marxist government to reconsider their antireligious outlook, resulting in enhanced liberty of worship and "increasing admission that church people could contribute to the betterment of Cuban society." [5] With this, Cuban Catholics were encouraged to take a more active role in the Cuban society, and examine the revolution. The revolution was praised for contributing to the "new man" that would be committed to common good instead of individual objectives, and socialism was to be accepted as a solution to chronic socioeconomic injustice. [5] According to the interviews of Cuban seminarians in San Carlos and San Ambrosio Seminary throughout 1970s and 1980s, most new clergymen came from irreligious families and sought "a more transcendental explanation of life than that provided by atheistic materialism". Most seminarians also felt a "strong obligation to infuse Cuban society with Christian ideals" and found "evangelization and participation in the Revolution" necessary. [5]

The amendments to the Cuban constitution in 1971 and 1976 reinstated and reaffirmed religious freedom in Cuba. In its 1978 party platform, the Communist Party of Cuba declared that both religious and irreligious were to have equal rights and responsibilities, while also stating opposition to antireligious campaigns and "administrative measures against religion". [5] The platform also celebrated the "increasing support of Christians for liberation movements". [5] The Second Party Congress in 1980 allowed for and voiced the need for strategic alliances between Christians and Marxists. The concept of strategic alliance between Christianity and Marxism in Cuba was also suggested by Fidel Castro, during his 1972 speech to Christians for Socialism in Chile:

When we look to history we see evolution. There was a time when the Christian religion, which used to be the religion of the slaves, became the religion of the emperors, of the court, the religion of patricians. As we go further into history, we see how men have made serious mistakes in the name of religion. I'm not going to talk about how men made even worse mistakes in their role as politicians. It was on the basis of such realities that I said we had to fight together to achieve these aims for, I ask where do the contradictions between Christian teachings and socialist teachings lie? Where? We both wish to struggle on behalf of man for the welfare of man, for the happiness of man. [5]

Castro reaffirmed this stance in his speech to Jamaican Council of Churches in 1977, stating that "are no contradictions between the aims of religion and the aims of socialism". [5] Castro clarified that while public education in Cuba was to have "an orientation that opposes the religious view in the fields of philosophy or history", he does not oppose the import of religious publications to Cuba and would finance individual churches if the local community requested one. He claimed that the Cuban revolution was unique in that it had "few conflicts with religion", which he ascribed to the "astuteness of church leaders, the growing number of progressive Christians, as well as to the desire of the Cuban government not to present the Revolution as an enemy of religion." [5]

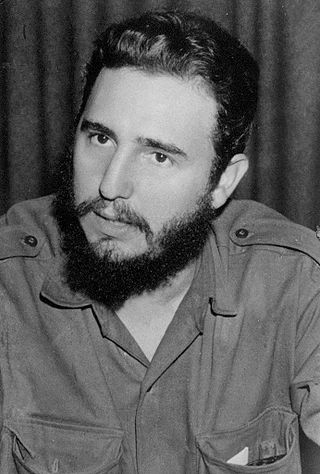

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 2008. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist and Cuban nationalist, he also served as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba from 1965 until 2011. Under his administration, Cuba became a one-party communist state; industry and business were nationalized, and socialist reforms were implemented throughout society.

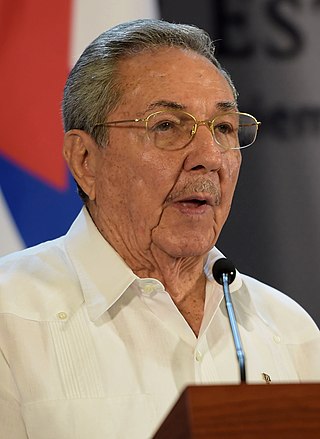

Raúl Modesto Castro Ruz is a Cuban retired politician and general who served as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, the most senior position in the one-party communist state, from 2011 to 2021, and President of Cuba between 2008 and 2018, succeeding his brother Fidel Castro.

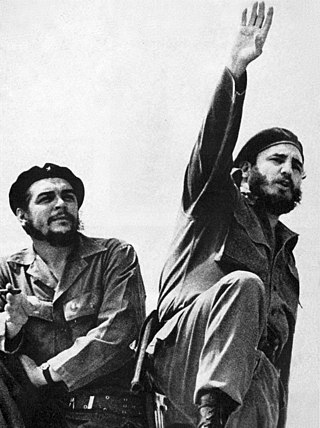

The Cuban Revolution was the military and political overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's dictatorship, which had reigned as the government of Cuba between 1952 and 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, which saw Batista topple the nascent Cuban democracy and consolidate power. Among those opposing the coup was Fidel Castro, then a novice attorney who attempted to contest the coup through Cuba's judiciary. Once these efforts proved fruitless, Fidel Castro and his brother Raúl led an armed attack on the Cuban military's Moncada Barracks on 26 July 1953.

The relations between the Catholic Church and the state have been constantly evolving with various forms of government, some of them controversial in retrospect. In its history, the Church has had to deal with various concepts and systems of governance, from the Roman Empire to the medieval divine right of kings, from nineteenth- and twentieth-century concepts of democracy and pluralism to the appearance of left-wing and right-wing dictatorial regimes. The Second Vatican Council's decree Dignitatis humanae stated that religious freedom is a civil right that should be recognized in constitutional law.

The 26 July Movement was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates the failed 1953 attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba, part of an attempt to overthrow the dictator Fulgencio Batista.

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to separate the church from public and political life.

Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado was a Cuban politician who served as the president of Cuba from 1959 to 1976. He was a close ally of Cuban revolutionary and longtime leader Fidel Castro.

State atheism or atheist state is the incorporation of hard atheism or non-theism into political regimes. It is considered the opposite of theocracy and may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments. To some extent, it is a religion-state relationship that is usually ideologically linked to irreligion and the promotion of irreligion or atheism. State atheism may refer to a government's promotion of anti-clericalism, which opposes religious institutional power and influence in all aspects of public and political life, including the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen. In some instances, religious symbols and public practices that were once held by religions were replaced with secularized versions of them. State atheism in these cases is considered as not being politically neutral toward religion, and therefore it is often considered non-secular.

The Catholic Church in Cuba is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome. Catholics make up approximately half of the population of Cuba.

Christianity is the most widely professed religion in Cuba, with Catholicism being its largest denomination. A significant share of the Cuban population is either non-religious or practices folk religions.

The Cuban Revolution was the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's regime by the 26th of July Movement and the establishment of a new Cuban government led by Fidel Castro in 1959.

Mario Chanes de Armas was a former Cuban revolutionary and ally of Fidel Castro. He was a veteran of the attack on the Moncada barracks in July 1953 and served time in Batista's New Model Prison on the Isle of Pines with fellow revolutionary Fidel Castro. After Castro's rise to power, he was labeled an enemy of the regime and imprisoned for almost 30 years.

While Protestants arrived in the island of Cuba early in its colonial days, most of their churches did not flourish until the 20th century with the assistance of American missionaries. In the early 20th century, Cuban Protestant churches were greatly aided by various American missionaries who assisted in the work in the churches and also provided support from their home churches. When Fidel Castro’s regime overtook the country in 1959, Protestant churches were legally allowed to continue. Nevertheless, certain incidents as detailed below, and religious persecution kept them from prospering. During the Special Period that began in 1991, Protestant churches began to flourish once again and today have become a primary religious group of Cuba. The Protestant population of Cuba is estimated at 11%.

Blas Roca Calderio was a Cuban politician and Marxist theorist who served as President of the National Assembly of People's Power from 1976 to 1981. He was also general secretary of the pre-1959 revolution Communist Party of Cuba for 28 years and editor of the communist newspaper Hoy. He was a signatory of the 1940 Constitution of Cuba, and chaired the committee that wrote the country's first socialist constitution in 1976.

Fidelismo, otherwise known as Castroism, consists of the personal beliefs of Fidel Castro, which were often anti-imperialist, Cuban nationalist, supportive of Hispanidad, and later Marxism–Leninist. Castro described two historical figures as being particular influences on his political viewpoints: the Cuban anti-imperialist revolutionary José Martí, and the German sociologist and theorist Karl Marx. The thought of Che Guevara and Jules Régis Debray have also been important influences on Fidel Castro.

The Communist Party of Cuba is the sole ruling party of Cuba. It was founded on 3 October 1965 as the successor to the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution, which was in turn made up of the 26th of July Movement and Popular Socialist Party that seized power in Cuba after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. The party governs Cuba as an authoritarian one-party state where dissidence and political opposition are prohibited and repressed. The Cuban constitution ascribes the role of the party to be the "leading force of society and of the state".

The Progressive Action Party was a Cuban political party led by Fulgencio Batista. The party was founded on 1 April 1949, in the aftermath of the 1948 general elections, under the name of Unitary Action Party. It presented its first manifesto a few months later, on 1 August. In 1952, certain to lose the election, Batista made a coup d'etat by seizing the Presidency.

The consolidation of the Cuban Revolution is a period in Cuban history typically defined as starting in the aftermath of the revolution in 1959 and ending in 1962, after the total political consolidation of Fidel Castro as the maximum leader of Cuba. The period encompasses early domestic reforms, human rights violations, and the ousting of various political groups. This period of political consolidation climaxed with the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, which then cooled much of the international contestation that arose alongside Castro's bolstering of power.

The slogan "revolution first, elections later" was coined by Fidel Castro in a speech given on April 9, 1959. The speech famously announced the postponement of the elections promised by Fidel Castro, which were scheduled to occur after the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista. The announcement was the beginning of an electoral delay that culminated in the solidification of Fidel Castro's rule over Cuba. On May Day, 1960, Fidel Castro would outright condemn elections as corrupt, and cancel all future elections.

The betrayal thesis is an interpretation of the Cuban Revolution that supposes that the revolution was the culmination of a democratic resistance to the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. After the success of the revolution in 1959, the rebel leader Fidel Castro began to consolidate political power, and associate with communist officials. This political turn is considered a "betrayal" of the original ethos of the revolution, according to proponents of the betrayal thesis.