A gender role, or sex role, is a set of socially accepted behaviors and attitudes deemed appropriate or desirable for individuals based on their sex. Gender roles are usually centered on conceptions of masculinity and femininity.

Triple oppression, also called double jeopardy, Jane Crow, or triple exploitation, is a theory developed by black socialists in the United States, such as Claudia Jones. The theory states that a connection exists between various types of oppression, specifically classism, racism, and sexism. It hypothesizes that all three types of oppression need to be overcome at once.

Feminist economics is the critical study of economics and economies, with a focus on gender-aware and inclusive economic inquiry and policy analysis. Feminist economic researchers include academics, activists, policy theorists, and practitioners. Much feminist economic research focuses on topics that have been neglected in the field, such as care work, intimate partner violence, or on economic theories which could be improved through better incorporation of gendered effects and interactions, such as between paid and unpaid sectors of economies. Other feminist scholars have engaged in new forms of data collection and measurement such as the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), and more gender-aware theories such as the capabilities approach. Feminist economics is oriented towards the goal of "enhancing the well-being of children, women, and men in local, national, and transnational communities."

A glass ceiling is a metaphor usually applied to people of marginalized genders, used to represent an invisible barrier that prevents an oppressed demographic from rising beyond a certain level in a hierarchy. The metaphor was first used by feminists in reference to barriers in the careers of high-achieving women. It was coined by Marilyn Loden during a speech in 1978.

Emotional labor is the process of managing feelings and expressions to fulfill the emotional requirements of a job. More specifically, workers are expected to regulate their personas during interactions with customers, co-workers, clients, and managers. This includes analysis and decision-making in terms of the expression of emotion, whether actually felt or not, as well as its opposite: the suppression of emotions that are felt but not expressed. This is done so as to produce a certain feeling in the customer or client that will allow the company or organization to succeed.

Feminization of poverty refers to a trend of increasing inequality in living standards between men and women due to the widening gender gap in poverty. This phenomenon largely links to how women and children are disproportionately represented within the lower socioeconomic status community in comparison to men within the same socioeconomic status. Causes of the feminization of poverty include the structure of family and household, employment, sexual violence, education, climate change, "femonomics" and health. The traditional stereotypes of women remain embedded in many cultures restricting income opportunities and community involvement for many women. Matched with a low foundation income, this can manifest to a cycle of poverty and thus an inter-generational issue.

A double burden is the workload of people who work to earn money, but who are also responsible for significant amounts of unpaid domestic labor. This phenomenon is also known as the Second Shift as in Arlie Hochschild's book of the same name. In couples where both partners have paid jobs, women often spend significantly more time than men on household chores and caring work, such as childrearing or caring for sick family members. This outcome is determined in large part by traditional gender roles that have been accepted by society over time. Labor market constraints also play a role in determining who does the bulk of unpaid work.

Emotion work is understood as the art of trying to change in degree or quality an emotion or feeling.

A stay-at-home mother is a mother who is the primary caregiver of the children. The male equivalent is the stay-at-home dad. The gender-neutral term is stay-at-home parent. Stay-at-home mom is distinct from a mother taking paid or unpaid parental leave from her job. The stay-at-home mom is forgoing paid employment in order to care for her children by choice or by circumstance. A stay-at-home mother might stay out of the paid workforce for a few months, a few years, or many years.

Gender inequality is the social phenomenon in which people are not treated equally on the basis of gender. This inequality can be caused by gender discrimination or sexism. The treatment may arise from distinctions regarding biology, psychology, or cultural norms prevalent in the society. Some of these distinctions are empirically grounded, while others appear to be social constructs. While current policies around the world cause inequality among individuals, it is women who are most affected. Gender inequality weakens women in many areas such as health, education, and business life. Studies show the different experiences of genders across many domains including education, life expectancy, personality, interests, family life, careers, and political affiliation. Gender inequality is experienced differently across different cultures.

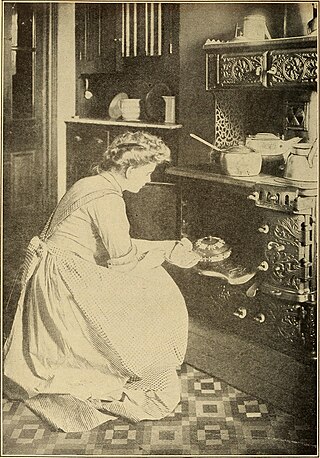

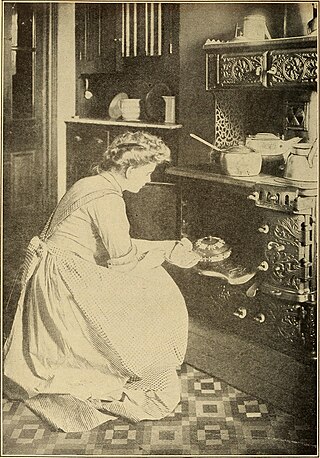

Women's work is a field of labour assumed to be solely the realm of women and associated with specific stereotypical jobs considered as uniquely feminine or domestic duties throughout history. It is most commonly used in reference to the unpaid labor typically performed by that of a mother or wife to upkeep the home and children.

Unpaid labor or unpaid work is defined as labor or work that does not receive any direct remuneration. This is a form of non-market work which can fall into one of two categories: (1) unpaid work that is placed within the production boundary of the System of National Accounts (SNA), such as gross domestic product (GDP); and (2) unpaid work that falls outside of the production boundary, such as domestic labor that occurs inside households for their consumption. Unpaid labor is visible in many forms and is not limited to activities within a household. Other types of unpaid labor activities include volunteering as a form of charity work and interning as a form of unpaid employment. In a lot of countries, unpaid domestic work in the household is typically performed by women, due to gender inequality and gender norms, which can result in high-stress levels in women attempting to balance unpaid work and paid employment. In poorer countries, this work is sometimes performed by children.

Care work includes all tasks directly involving the care of others. The majority of care work is provided without any expectation of immediate pecuniary reward. Instead, it is undertaken out of affection, social norms or a sense of responsibility for others. It can also be a form of paid employment.

Women migrant workers from developing countries engage in paid employment in countries where they are not citizens. While women have traditionally been considered companions to their husbands in the migratory process, most adult migrant women today are employed in their own right. In 2017, of the 168 million migrant workers, over 68 million were women. The increase in proportion of women migrant workers since the early twentieth century is often referred to as the "feminization of migration".

The gender pay gap or gender wage gap is the average difference between the remuneration for men and women who are employed. Women are generally found to be paid less than men. There are two distinct numbers regarding the pay gap: non-adjusted versus adjusted pay gap. The latter typically takes into account differences in hours worked, occupations chosen, education and job experience. In other words, the adjusted values represent how much women and men make for the same work, while the non-adjusted values represent how much the average man and woman make in total. In the United States, for example, the non-adjusted average woman's annual salary is 79–83% of the average man's salary, compared to 95–99% for the adjusted average salary.

Digital labor or digital labour represents an emergent form of labor characterized by the production of value through interaction with information and communication technologies such as digital platforms or artificial intelligence. Examples of digital labor include on-demand platforms, micro-working, and user-generated data for digital platforms such as social media. Digital labor describes work that encompasses a variety of online tasks. If a country has the structure to maintain a digital economy, digital labor can generate income for individuals without the limitations of physical barriers.

Reproductive labor or work is often associated with care giving and domestic housework roles including cleaning, cooking, child care, and the unpaid domestic labor force. The term has taken on a role in feminist philosophy and discourse as a way of calling attention to how women in particular are assigned to the domestic sphere, where the labor is reproductive and thus uncompensated and unrecognized in a capitalist system. These theories have evolved as a parallel of histories focusing on the entrance of women into the labor force in the 1970s, providing an intersectionalist approach that recognizes that women have been a part of the labor force since before their incorporation into mainstream industry if reproductive labor is considered.

Even in the modern era, gender inequality remains an issue in Japan. In 2015, the country had a per-capita income of US$38,883, ranking 22nd of the 188 countries, and No. 18 in the Human Development Index. In the 2019 Gender Inequality Index report, it was ranked 17th out of the participating 162 countries, ahead of Germany, the UK and the US, performing especially well on the reproductive health and higher education attainment indices. Despite this, gender inequality still exists in Japan due to the persistence of gender norms in Japanese society rooted in traditional religious values and government reforms. Gender-based inequality manifests in various aspects from the family, or ie, to political representation, to education, playing particular roles in employment opportunities and income, and occurs largely as a result of defined roles in traditional and modern Japanese society. Inequality also lies within divorce of heterosexual couples and the marriage of same sex couples due to both a lack of protective divorce laws and the presence of restrictive marriage laws. In consequence to these traditional gender roles, self-rated health surveys show variances in reported poor health, population decline, reinforced gendered education and social expectations, and inequalities in the LGBTQ+ community.

Gemma Hartley is an American author and journalist best known for a viral article in Harper's Bazaar on emotional labor and her subsequent book Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way Forward.

Cognitive labor is sociological and feminist concept referring to the invisible mental work many women do in relationships and families. It is related to invisible labor, emotional labor, and unpaid work while emphasizing the cost of planning, organizing, scheduling, managing and worrying, in addition to "executing." The distribution of cognitive labor falls disproportionately on women. Handling the majority of cognitive labor is a burden that prevents women from pursuing opportunities or achieving greater health and happiness. A recommendation for balancing cognitive labor is making it more explicit and visible.