| Language | Cluster | Dialects | Alternate spellings | Own name for language | Endonym(s) | Other names (location-based) | Other names for language | Exonym(s) | Speakers | Location(s) |

|---|

| Damlanci | unclassified | | Damlawa | Damlanci | | | | | 500-1000 ethnic population, but language now spoken by those over 50, although not moribund | Bauchi State, Alkaleri LGA, Maccido village |

| Gwa | unclassified | | | | | | | | Fewer than 1,000 (LA 1971) | Bauchi State, Toro LGA |

| | | | | | | | | | |

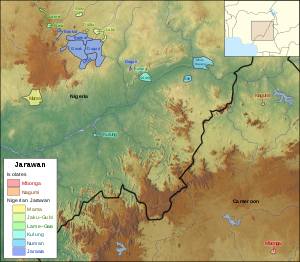

| Jar cluster | | | Dṣ’arawa (Koelle 1854), Jarawa | | | | Jar, Jarawan Kogi, Jarawan Kasa, Jaracin Kogi/Kasa | | | Plateau, Bauchi and Adamawa States |

| Bobar (?) | Jar | | | | | | | | | Bauchi State, precise Location(s) unknown. May not exist as survey in 2007 failed to find such a language |

| Doori | Jar | Previous sources (e.g. Maddieson & Williamson 1975) divided Duguri into a number of regional dialects, but this may not be valid since all Doori essentially speak mutually intelligible lects | | Dõõri | | | Duguranci | Dugurawa | | Bauchi State, Alkaleri, Tafawa Balewa LGAs; Plateau State, Kanam LGA |

| Galamkya | Jar | may be dialect of Mbat | | | | Kanna | Jar, Jarawan Kogi, Garaka | Badawa, Mbadawa | 10,000 (SIL) | North-western Kanam LGA, southwest of Mbat, including Gyangyang 2 and Gidgid |

| Gwak | Jar | | Gingwak | | | | Jaranci | Jarawan Bununu, Jaracin Kasa | 19,000 (LA 1971) | Dass town and southward to Tafawa Balewa, west of the Gongola River, in Dass and Tafawa Balewa LGAs, Bauchi State |

| Kantana | Jar | | | | | | Kantanawa | | | Plateau State, Kanam LGA |

| Ligri | Jar | | | | | | | | 800 speakers (Ayuba est. 2008). | Taraba State, Karim Lamido LGA |

| Mbat | Jar | | Mbada, Bat, Bada, Baɗa | | | Kanna | Jar, Jarawan Kogi, Garaka | Badawa, Mbadawa | 10,000 (SIL) | North-central part of Kanam LGA, Plateau State, centered at Gagdi-Gum |

| Zhar | Jar | Dumbulawa (Sutumi village) may speak a Ɓankal dialect | | Zhar | | Ɓankal, Bankal, Bankala | Bankalanci, Baranci | Bankalawa | 20,000 (LA 1971) | Dass town and northward to Bauchi town, west of the Gongola River, in Dass, Bauchi, and Toro LGAs, Bauchi State |

|

| Jaku-Gubi cluster | | | | | | | | | | |

| Labɨr | | | Lábɨ́r | | | Jaku, Jaaku | Jakanci | | Spoken in about 10 villages, perhaps 5000 speakers (2019 est.) | Bauchi State, south of the Bauchi-Gombe Road, from the Gongola River at Kanyallo, in Bauchi LGA, to Gar in Alkaleri LGA |

| Shɨkɨ | | | | | | Gubi, Guba | | Gubawa | 300 (LA 1971) | Bauchi State, Bauchi LGA |

| Dulbu | | | | | | | | | 80 (LA 1971) | Bauchi State, Bauchi LGA |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| Lame cluster | | | | | | | | | 2,000 (1973 SIL) | Bauchi State, Toro LGA, Lame district |

| Ruhu | Lame | | Rufu, Rùhû | | | | | Rufawa | There were said to be no speakers remaining in 1987 | |

| Mbaru | Lame | | Mbárù, Bambaro, Bamburo, Bambara, Bombaro, Bomboro, Bamboro | | | | | Bomborawa, Bunborawa | 3500-4500 (CAPRO 1995a). Tulu town, Toro LGA, Bauchi State | |

| Gura | Lame | | | Tu–Gura | sg. Ba–Gura, pl. Mo–Gura | | Agari, Agbiri | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| Mbula cluster | | | | | | | | | 7,900 (1952); 25,000 (1972 Barrett); 23,447 (1977) Blench: not clear as to whether for Mbula or both Mbula and Bwazza.) | Adamawa State, Numan, Shelleng and Song LGAs |

| Mbula | Mbula | | | | | | | | | |

| Tambo | Mbula | | | | | | | | | |

| Bwazza | Mbula | No dialects | | Ɓwà Ɓwàzà pl. àɓwàzà | Ɓwázà | Bare, Bere [name of a town] | | | | Adamawa State, Demsa, Numan, Shelleng and Song LGAs. 26 villages. |

| Ɓile | Mbula | Kun–Ɓíilé is said to be mutually intelligible with Mbula | Bille, Bili, Bilanci | Kun–Ɓíilé | ɓa Ɓíilé | | | | 30,000 (CAPRO, 1992); there are 36 villages reported to be entirely Ɓile-speaking, and another 16 where some Ɓile is spoken | Adamawa State, Numan LGA, 25 km south of Numan, east of the Wukari road. |

| | | | | | | | | | |

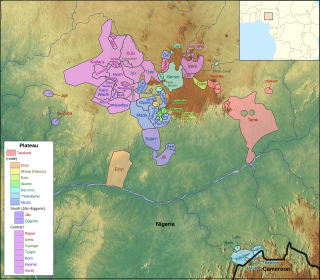

| Mama | n/a | | | | | | Kwarra | | 7,891 (1922 Temple); 6,155 (1934 Ames); 20,000 (1973 SIL) | Nasarawa State, Akwanga LGA |

| | | | | | | | | | |

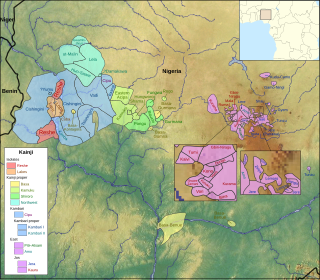

| Kulung | n/a | | | Kúkùlúŋ | Bákùlúng | Bambur, Wurkum | | Wurkunawa (Gowers 1907) | 15,000 (SIL) | Taraba State, Karim Lamido LGA, at Balasa, Bambur and Kirim; Wukari LGA, at Gada Mayo |