Gay-friendly or LGBT-friendly places, policies, people, or institutions are those that are open and welcoming to gay or LGBT people. They typically aim to create an environment that is supportive, respectful, and non-judgmental towards the LGBT community. The term "gay-friendly" originated in the late 20th century in North America, as a byproduct of a gradual implementation of gay rights, greater acceptance of LGBT people in society, and the recognition of LGBT people as a distinct consumer group for businesses.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Fiji have evolved rapidly over the years. In 1997, Fiji became the second country in the world after South Africa to explicitly protect against discrimination based on sexual orientation in its Constitution. In 2009, the Constitution was abolished. The new Constitution, promulgated in September 2013, bans discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity or expression. However, same-sex marriage remains banned in Fiji and reports of societal discrimination and bullying are not uncommon.

The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland have developed significantly over time. Today, lesbian, gay and bisexual rights are considered to be advanced by international standards.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Kenya face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Sodomy is a felony per Section 162 of the Kenyan Penal Code, punishable by 21 years' imprisonment, and any sexual practices are a felony under section 165 of the same statute, punishable by five years' imprisonment. On 24 May 2019, the High Court of Kenya refused an order to declare sections 162 and 165 unconstitutional. The state does not recognise any relationships between persons of the same sex; same-sex marriage is banned under the Kenyan Constitution since 2010. There are no explicit protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Adoption is restricted to heterosexual couples only.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Cyprus have evolved in recent years, but LGBT people still face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female expressions of same-sex sexual activity were decriminalised in 1998, and civil unions which grant several of the rights and benefits of marriage have been legal since December 2015. Conversion therapy was banned in Cyprus in May 2023. However, adoption rights in Cyprus are reserved for heterosexual couples only.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in the British Crown dependency of the Isle of Man have evolved substantially since the early 2000s. Private and consensual acts of male homosexuality on the island were decriminalised in 1992. LGBT rights have been extended and recognised in law since then, such as an equal age of consent (2006), employment protection from discrimination (2006), gender identity recognition (2009), the right to enter into a civil partnership (2011), the right to adopt children (2011) and the right to enter into a civil marriage (2016).

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Angola have seen improvements in the early 21st century. In November 2020, the National Assembly approved a new penal code, which legalised consenting same-sex sexual activity. Additionally, employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has been banned, making Angola one of the few African countries to have such protections for LGBT people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Botswana face legal issues not experienced by non-LGBT citizens. Both female and male same-sex sexual acts have been legal in Botswana since 11 June 2019 after a unanimous ruling by the High Court of Botswana. Despite an appeal by the government, the ruling was upheld by the Botswana Court of Appeal on 29 November 2021.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Dominica face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Homosexuality has been legal since 2024, when the High Court struck down the country's colonial-era sodomy law. Dominica provides no recognition to same-sex unions, whether in the form of marriage or civil unions, and no law prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Uganda face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women in Uganda. It was originally criminalised by British colonial laws introduced when Uganda became a British protectorate, and these laws have been retained since the country gained its independence.

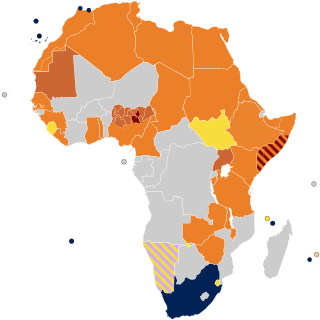

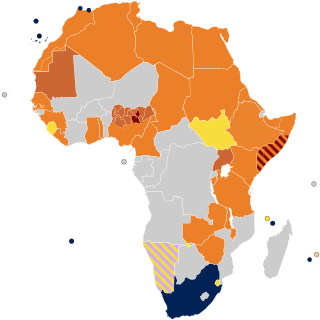

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are generally poor in comparison to the Americas, Western Europe and Oceania.

The Act to Make Provisions for the Prohibition of Relationship Between Persons of the Same Sex, Celebration of Marriage by Them, and for Other Matters Connected Therewith, also known as the Same Sex (Prohibition) Act 2006, was a controversial draft bill that was first put before the both houses of the National Assembly of Nigeria in early 2007. Seven years later, another draft was passed into legislation by president Goodluck Jonathan as the Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act 2013.

Oceania is, like other regions, quite diverse in its laws regarding LGBT rights. This ranges from significant rights, including same-sex marriage – granted to the LGBT+ community in New Zealand, Australia, Guam, Hawaii, Easter Island, Northern Mariana Islands, Wallis and Futuna, New Caledonia, French Polynesia and the Pitcairn Islands – to remaining criminal penalties for homosexual activity in six countries and one territory. Although acceptance is growing across the Pacific, violence and social stigma remain issues for LGBT+ communities. This also leads to problems with healthcare, including access to HIV treatment in countries such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands where homosexuality is criminalised.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Bermuda, a British Overseas Territory, face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Homosexuality is legal in Bermuda, but the territory has long held a reputation for being homophobic and intolerant. Since 2013, the Human Rights Act has prohibited discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Barbados do not possess the same legal rights as non-LGBT people. In December 2022, the courts ruled Barbados' laws against buggery and "gross indecency" were unconstitutional and struck them from the Sexual Offences Act. However, there is no recognition of same-sex relationships and only limited legal protections against discrimination.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Belize face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT citizens, although attitudes have been changing in recent years. Same-sex sexual activity was decriminalized in Belize in 2016, when the Supreme Court declared Belize's anti-sodomy law unconstitutional. Belize's constitution prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, which Belizean courts have interpreted to include sexual orientation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people are generally discriminated against in the Maldives.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people living in Nauru may face legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since May 2016, but there are no legal recognition of same-sex unions, or protections against discrimination in the workplace or the provision of goods and services.

This is a timeline of notable events in the history of non-heterosexual conforming people of African ancestry, who may identify as LGBTIQGNC, men who have sex with men, or related culturally specific identities. This timeline includes events both in Africa, the Americas and Europe and in the global African diaspora, as the histories are very deeply linked.

The history of sexual minorities in Sri Lanka covered in this article dates back to a couple of centuries before the start of the Vikram Samvat era, although it is highly likely that archaeology predating this period exists. There are virtually zero historical records of sexual minorities in the Latin script dating prior to colonialism. The concept of Sri Lanka did not exist prior to colonialism, and the term 'lanka' translates to 'island'.

![.mw-parser-output .hlist dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul{margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt,.mw-parser-output .hlist li{margin:0;display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ul{display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist .mw-empty-li{display:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dt::after{content:": "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li::after{content:" * ";font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li:last-child::after{content:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:first-child::before{content:" (";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:last-child::after{content:")";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol{counter-reset:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li{counter-increment:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li::before{content:" "counter(listitem)"\a0 "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li ol>li:first-child::before{content:" ("counter(listitem)"\a0 "}

.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:inline;font-size:88%;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .navbar-collapse{float:left;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .navbar-boxtext{word-spacing:0}.mw-parser-output .navbar ul{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;line-height:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::before{margin-right:-0.125em;content:"[ "}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::after{margin-left:-0.125em;content:" ]"}.mw-parser-output .navbar li{word-spacing:-0.125em}.mw-parser-output .navbar a>span,.mw-parser-output .navbar a>abbr{text-decoration:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-mini abbr{font-variant:small-caps;border-bottom:none;text-decoration:none;cursor:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-full{font-size:114%;margin:0 7em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-mini{font-size:114%;margin:0 4em}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(--color-base)!important}@media(prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(--color-base)!important}}@media print{.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:none!important}}

v

t

e

Worldwide laws regarding same-sex intercourse, unions and expression

Same-sex intercourse illegal. Penalties:

.mw-parser-output .legend{page-break-inside:avoid;break-inside:avoid-column}.mw-parser-output .legend-color{display:inline-block;min-width:1.25em;height:1.25em;line-height:1.25;margin:1px 0;text-align:center;border:1px solid black;background-color:transparent;color:black}.mw-parser-output .legend-text{}

Death

Prison; death not enforced

Death under militias

Prison, with arrests or detention

Prison, not enforced

Same-sex intercourse legal. Recognition of unions:

Marriage

Extraterritorial marriage

Civil unions

Limited domestic

Limited foreign

Optional certification

None

Restrictions of expression, not enforced

Restrictions of association with arrests or detention

No imprisonment in the past three years or moratorium on law.

Marriage not available locally. Some jurisdictions may perform other types of partnerships. World laws pertaining to homosexual relationships and expression.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d1/World_laws_pertaining_to_homosexual_relationships_and_expression.svg/450px-World_laws_pertaining_to_homosexual_relationships_and_expression.svg.png)