Holkham National Nature Reserve is England's largest national nature reserve (NNR). It is on the Norfolk coast between Burnham Overy Staithe and Blakeney, and is managed by Natural England with the cooperation of the Holkham Estate. Its 3,900 hectares comprise a wide range of habitats, including grazing marsh, woodland, salt marsh, sand dunes and foreshore. The reserve is part of the North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest, and the larger area is additionally protected through Natura 2000, Special Protection Area (SPA) and Ramsar listings, and is part of both an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and a World Biosphere Reserve. Holkham NNR is important for its wintering wildfowl, especially pink-footed geese, Eurasian wigeon and brant geese, but it also has breeding waders, and attracts many migrating birds in autumn. Many scarce invertebrates and plants can be found in the dunes, and the reserve is one of the only two sites in the UK to have an antlion colony.

A salt marsh, saltmarsh or salting, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the tides. It is dominated by dense stands of salt-tolerant plants such as herbs, grasses, or low shrubs. These plants are terrestrial in origin and are essential to the stability of the salt marsh in trapping and binding sediments. Salt marshes play a large role in the aquatic food web and the delivery of nutrients to coastal waters. They also support terrestrial animals and provide coastal protection.

The Tantramar Marshes, also known as the Tintamarre National Wildlife Area, is a tidal saltmarsh around the Bay of Fundy on the Isthmus of Chignecto. The area borders between Route 940, Route 16 and Route 2 near Sackville, New Brunswick. The government of Canada proposed the boundaries of the Tantramar Marshes in 1966 and was declared a National Wildlife Area in 1978.

A tidal marsh is a marsh found along rivers, coasts and estuaries which floods and drains by the tidal movement of the adjacent estuary, sea or ocean. Tidal marshes experience many overlapping persistent cycles, including diurnal and semi-diurnal tides, day-night temperature fluctuations, spring-neap tides, seasonal vegetation growth and decay, upland runoff, decadal climate variations, and centennial to millennial trends in sea level and climate.

Coastal management is defence against flooding and erosion, and techniques that stop erosion to claim lands. Protection against rising sea levels in the 21st century is crucial, as sea level rise accelerates due to climate change. Changes in sea level damage beaches and coastal systems are expected to rise at an increasing rate, causing coastal sediments to be disturbed by tidal energy.

Climate change adaptation is the process of adjusting to the effects of climate change. These can be both current or expected impacts. Adaptation aims to moderate or avoid harm for people, and is usually done alongside climate change mitigation. It also aims to exploit opportunities. Humans may also intervene to help adjust for natural systems. There are many adaptation strategies or options. For instance, building hospitals that can withstand natural disasters, roads that don't get washed away in the face of rains and floods. They can help manage impacts and risks to people and nature. The four types of adaptation actions are infrastructural, institutional, behavioural and nature-based options. Some examples of these are building seawalls or inland flood defenses, providing new insurance schemes, changing crop planting times or varieties, and installing green roofs or green spaces. Adaptation can be reactive or proactive.

Marine ecosystems are the largest of Earth's aquatic ecosystems and exist in waters that have a high salt content. These systems contrast with freshwater ecosystems, which have a lower salt content. Marine waters cover more than 70% of the surface of the Earth and account for more than 97% of Earth's water supply and 90% of habitable space on Earth. Seawater has an average salinity of 35 parts per thousand of water. Actual salinity varies among different marine ecosystems. Marine ecosystems can be divided into many zones depending upon water depth and shoreline features. The oceanic zone is the vast open part of the ocean where animals such as whales, sharks, and tuna live. The benthic zone consists of substrates below water where many invertebrates live. The intertidal zone is the area between high and low tides. Other near-shore (neritic) zones can include mudflats, seagrass meadows, mangroves, rocky intertidal systems, salt marshes, coral reefs, lagoons. In the deep water, hydrothermal vents may occur where chemosynthetic sulfur bacteria form the base of the food web.

Flood management describes methods used to reduce or prevent the detrimental effects of flood waters. Flooding can be caused by a mix of both natural processes, such as extreme weather upstream, and human changes to waterbodies and runoff. Flood management methods can be either of the structural type and of the non-structural type. Structural methods hold back floodwaters physically, while non-structural methods do not. Building hard infrastructure to prevent flooding, such as flood walls, is effective at managing flooding. However, it is best practice within landscape engineering to rely more on soft infrastructure and natural systems, such as marshes and flood plains, for handling the increase in water.

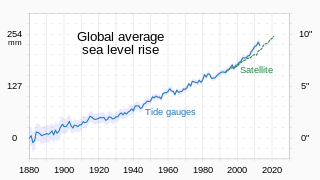

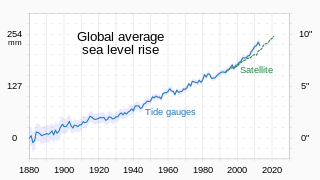

Between 1901 and 2018, the average sea level rose by 15–25 cm (6–10 in), with an increase of 2.3 mm (0.091 in) per year since the 1970s. This was faster than the sea level had ever risen over at least the past 3,000 years. The rate accelerated to 4.62 mm (0.182 in)/yr for the decade 2013–2022. Climate change due to human activities is the main cause. Between 1993 and 2018, melting ice sheets and glaciers accounted for 44% of sea level rise, with another 42% resulting from thermal expansion of water.

Low marsh is a tidal marsh zone located below the Mean Highwater Mark (MHM). Based on elevation, frequency of submersion, soil characteristics, vegetation, microbial community, and other metrics, salt marshes can be divided to into three distinct areas: low marsh, middle marsh/high marsh, and the upland zone. Low marsh is characterized as being flooded daily with each high tide, while remaining exposed during low tides.

Mangrove ecosystems represent natural capital capable of producing a wide range of goods and services for coastal environments and communities and society as a whole. Some of these outputs, such as timber, are freely exchanged in formal markets. Value is determined in these markets through exchange and quantified in terms of price. Mangroves are important for aquatic life and home for many species of fish.

Coastal flooding occurs when dry and low-lying land is submerged (flooded) by seawater. The range of a coastal flooding is a result of the elevation of floodwater that penetrates the inland which is controlled by the topography of the coastal land exposed to flooding. The seawater can flood the land via several different paths: direct flooding, overtopping or breaching of a barrier. Coastal flooding is largely a natural event. Due to the effects of climate change and an increase in the population living in coastal areas, the damage caused by coastal flood events has intensified and more people are being affected.

Coastal hazards are physical phenomena that expose a coastal area to the risk of property damage, loss of life, and environmental degradation. Rapid-onset hazards last a few minutes to several days and encompass significant cyclones accompanied by high-speed winds, waves, and surges or tsunamis created by submarine (undersea) earthquakes and landslides. Slow-onset hazards, such as erosion and gradual inundation, develop incrementally over extended periods.

Blue carbon is a concept within climate change mitigation that refers to "biologically driven carbon fluxes and storage in marine systems that are amenable to management". Most commonly, it refers to the role that tidal marshes, mangroves and seagrass meadows can play in carbon sequestration. These ecosystems can play an important role for climate change mitigation and ecosystem-based adaptation. However, when blue carbon ecosystems are degraded or lost, they release carbon back to the atmosphere, thereby adding to greenhouse gas emissions.

Coastal erosion in Louisiana is the process of steady depletion of wetlands along the state's coastline in marshes, swamps, and barrier islands, particularly affecting the alluvial basin surrounding the mouth of the Mississippi River. In the last century, coastal Louisiana has lost an estimated 4,833 square kilometers (1,866 sq mi) of land, approximately the size of Delaware's land area. Coast wide rates of wetland change have varied from −83.5 square kilometers (−32.2 sq mi) to −28.01 square kilometers (−10.81 sq mi) annually, with peak loss rates occurring during the 1970's. One consequence of coastal erosion is an increased vulnerability to hurricane storm surges, which affects the New Orleans metropolitan area and other communities in the region. The state has outlined a comprehensive master plan for coastal restoration and has begun to implement various restoration projects such as fresh water diversions, but certain zones will have to be prioritized and targeted for restoration efforts, as it is unlikely that all depleted wetlands can be rehabilitated.

Climate change in Delaware encompasses the effects of climate change, attributed to man-made increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, in the U.S. state of Delaware.

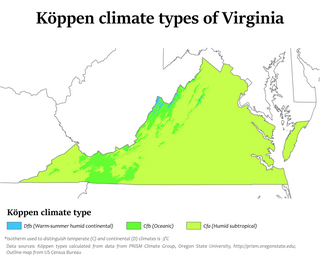

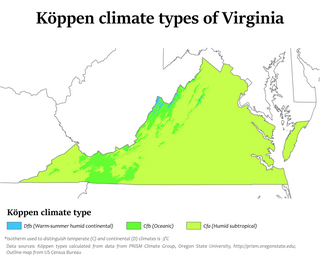

Climate change in Virginia encompasses the effects of climate change, attributed to man-made increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, in the U.S. state of Virginia.

Climate migration is a subset of climate-related mobility that refers to movement driven by the impact of sudden or gradual climate-exacerbated disasters, such as "abnormally heavy rainfalls, prolonged droughts, desertification, environmental degradation, or sea-level rise and cyclones". Gradual shifts in the environment tend to impact more people than sudden disasters. The majority of climate migrants move internally within their own countries, though a smaller number of climate-displaced people also move across national borders.

Sea level rise in New Zealand poses a significant threat to many communities, including New Zealand's larger population centres, and has major implications for infrastructure in coastal areas. In 2016, the Royal Society of New Zealand stated that a one-metre rise would cause coastal erosion and flooding, especially when combined with storm surges. Climate scientist Jim Salinger commented that New Zealand will have to abandon some coastal areas when the weather gets uncontrollable. Twelve of the fifteen largest towns and cities in New Zealand are coastal with 65% of communities and major infrastructure lying within five kilometres of the sea. The value of local government infrastructure that is vulnerable to sea level rise has been estimated at $5 billion. As flooding becomes more frequent, coastal homeowners will experience significant losses and displacement. Some may be forced to abandon their properties after a single, sudden disaster like a storm surge or flash flood or move away after a series of smaller flooding events that eventually become intolerable. Local and central government will face high costs from adaptive measures and continued provision of infrastructure when abandoning housing may be more efficient.