Animantarx is a genus of nodosaurid ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Early and Late Cretaceous of western North America. Like other nodosaurs, it would have been a slow-moving quadrupedal herbivore covered in heavy armor scutes, but without a tail club. The skull measures approximately 25 cm in length, suggesting the animal as a whole was no more than 3 meters long.

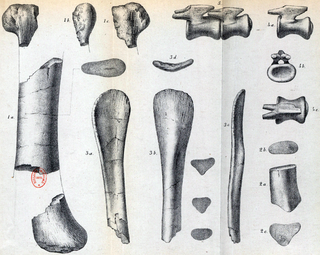

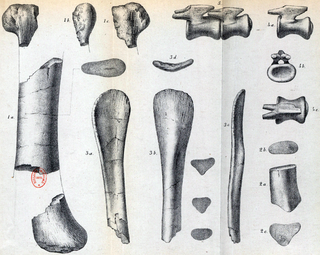

Hypselosaurus is a dubious genus of titanosaurian sauropod that lived in southern France during the Late Cretaceous, approximately 70 million years ago in the early Maastrichtian. Hypselosaurus was first described in 1846, but was not formally named until 1869, when Phillip Matheron named it under the binomial Hypselosaurus priscus. The holotype specimen includes a partial hindlimb and a pair of caudal vertebrae, and two eggshell fragments were found alongside these bones. Because of the proximity of these eggshells to the fossil remains, many later authors, including Matheron and Paul Gervais, have assigned several eggs from the same region of France all to Hypselosaurus, although the variation and differences between these eggs suggest that they do not all belong to the same taxon. Hypselosaurus has been found in the same formation as the dromaeosaurids Variraptor and Pyroraptor, the ornithopod Rhabdodon, and the ankylosaurian Rhodanosaurus, as well as indeterminate bones from other groups.

Ankylosauridae is a family of armored dinosaurs within Ankylosauria, and is the sister group to Nodosauridae. The oldest known ankylosaurids date to around 122 million years ago and went extinct 66 million years ago during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. These animals were mainly herbivorous and were obligate quadrupeds, with leaf-shaped teeth and robust, scute-covered bodies. Ankylosaurids possess a distinctly domed and short snout, wedge-shaped osteoderms on their skull, scutes along their torso, and a tail club.

Andesaurus is a genus of basal titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur which existed during the middle of the Cretaceous Period in South America. Like most sauropods, belonging to one of the largest animals ever to walk the Earth, it would have had a small head on the end of a long neck and an equally long tail.

Sauropelta is a genus of nodosaurid dinosaur that existed in the Early Cretaceous Period of North America. One species has been named. Anatomically, Sauropelta is one of the most well-understood nodosaurids, with fossilized remains recovered in the U.S. states of Wyoming, Montana, and possibly Utah. It is also the earliest known genus of nodosaurinae; most of its remains are found in a section of the Cloverly Formation dated to 108.5 million years ago.

Texasetes is a genus of ankylosaurian dinosaurs from the late Lower Cretaceous of North America. This poorly known genus has been recovered from the Paw Paw Formation near Haslet, Tarrant County, Texas, which has also produced the nodosaurid ankylosaur Pawpawsaurus.

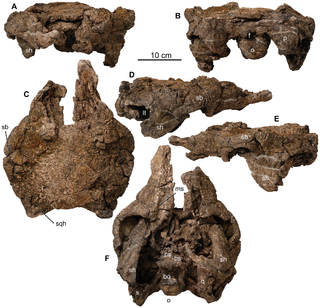

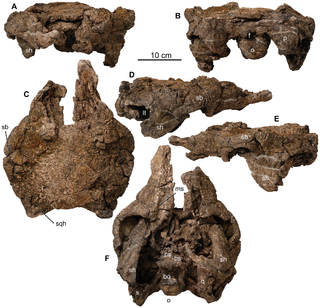

Cedarpelta is an extinct genus of basal ankylosaurid dinosaur from Utah that lived during the Late Cretaceous period in what is now the Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation. The type and only species, Cedarpelta bilbeyhallorum, is known from multiple specimens including partial skulls and postcranial material. It was named in 2001 by Kenneth Carpenter, James Kirkland, Don Burge, and John Bird. Cedarpelta has an estimated length of 7 metres and weight of 5 tonnes (11,023 lbs). The skull of Cedarpelta lacks extensive cranial ornamentation and is one of the only known ankylosaurs with individual skull bones that are not completely fused together.

Huabeisaurus was a genus of dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous. It was a sauropod which lived in what is present-day northern China. The type species, Huabeisaurus allocotus, was first described by Pang Qiqing and Cheng Zhengwu in 2000. Huabeisaurus is known from numerous remains found in the 1990s, which include teeth, partial limbs and vertebrae. Due to its relative completeness, Huabeisaurus represents a significant taxon for understanding sauropod evolution in Asia. Huabeisaurus comes from Kangdailiang and Houyu, Zhaojiagou Town, Tianzhen County, Shanxi province, China. The holotype was found in the unnamed upper member of the Huiquanpu Formation, which is Late Cretaceous (?Cenomanian–?Campanian) in age based on ostracods, charophytes, and fission-track dating.

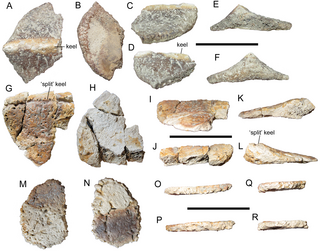

Mymoorapelta is a nodosaurid ankylosaur from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of western Colorado and central Utah, USA. The animal is known from a single species, Mymoorapelta maysi, and few specimens are known. The most complete specimen is the holotype individual from the Mygatt-Moore Quarry, which includes osteoderms, a partial skull, vertebrae, and other bones. It was initially described by James Kirkland and Kenneth Carpenter in 1994. Along with Gargoyleosaurus, it is one of the earliest known nodosaurids.

Tianzhenosaurus is a genus of ankylosaurid dinosaurs known from the Late Cretaceous Huiquanpu Formation of Shanxi Province, China. The genus contains two species, T. youngi and T. chengi. Some researchers have suggested that Tianzhenosaurus may represent a junior synonym of Saichania, an ankylosaurine from the Barun Goyot and Nemegt formations.

Venenosaurus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived in what is now Utah during the Early Cretaceous. Its type and only species is Venenosaurus dicrocei. Fossils of Venenosaurus were first discovered in 1998, by Denver Museum of Natural History volunteer Anthony DiCroce, and described as a new genus and species in 2001 by Virginia Tidwell and colleagues, who named the species for DiCroce. Venenosaurus was a relatively small sauropod, and was similar to Cedarosaurus, another sauropod from the Early Cretaceous of Utah.

Panoplosaurus is a genus of armoured dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada. Few specimens of the genus are known, all from the middle Campanian of the Dinosaur Park Formation, roughly 76 to 75 million years ago. It was first discovered in 1917, and named in 1919 by Lawrence Lambe, named for its extensive armour, meaning "well-armoured lizard". Panoplosaurus has at times been considered the proper name for material otherwise referred to as Edmontonia, complicating its phylogenetic and ecological interpretations, at one point being considered to have existed across Alberta, New Mexico and Texas, with specimens in institutions from Canada and the United States. The skull and skeleton of Panoplosaurus are similar to its relatives, but have a few significant differences, such as the lumpy form of the skull osteoderms, a completely fused shoulder blade, and regularly shaped plates on its neck and body lacking prominent spines. It was a quadrupedal animal, roughly 5 m (16 ft) long and 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) in weight. The skull has a short snout, with a very domed surface, and bony plates directly covering the cheek. The neck had circular groups of plates arranged around the top surface, both the forelimb and hindlimb were about the same length, and the hand may have only included three fingers. Almost the entire surface of the body was covered in plates, osteoderms and scutes of varying sizes, ranging from large elements along the skull and neck, to smaller, round bones underneath the chin and body, to small ossicles that filled in the spaces between other, larger osteoderms.

Antarctopelta is a genus of ankylosaurian dinosaur, a group of large, quadrupedal herbivores, that lived during the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period on what is now James Ross Island, Antarctica. Antarctopelta is the only known ankylosaur from Antarctica and a member of Parankylosauria. The only described specimen was found in 1986, the first dinosaur to be found on the continent, by Argentine geologists Eduardo Olivero and Robert Scasso. The fossils were later described in 2006 by paleontologists Leonardo Salgado and Zulma Gasparini, who named the type species A. oliveroi after Olivero.

Ahshislepelta is a monospecific genus of ankylosaur dinosaur from New Mexico that lived during the Late Cretaceous in what is now the Hunter Wash Member of the Kirtland Formation. The type and only species, Ahshislepelta minor, is known only from an incomplete postcranial skeleton of a small subadult or adult individual. It was named in 2011 by Michael Burns and Robert M. Sullivan. Based on the size of the humerus, Ahshislepelta is larger than Pinacosaurus mephistocephalus but smaller than Talarurus and Pinacosaurus grangeri.

Europelta is a monospecific genus of nodosaurid dinosaur from Spain that lived during the Early Cretaceous in what is now the lower Escucha Formation of the Teruel Province. The type and only species, Europelta carbonensis, is known from two associated partial skeletons, and represents the most complete ankylosaur known from Europe. Europelta was named in 2013 by James I. Kirkland and colleagues. Europelta has an estimated length of 5 metres and weight of 1.3 tonnes, making it the largest member of the clade Struthiosaurini.

Chuanqilong is a monospecific genus of basal ankylosaurid dinosaur from the Liaoning Province, China that lived during the Early Cretaceous in what is now the Jiufotang Formation. The type and only species, Chuanqilong chaoyangensis, is known from a nearly complete skeleton with a skull of a juvenile individual. It was described in 2014 by Fenglu Han, Wenjie Zheng, Dongyu Hu, Xing Xu, and Paul M. Barrett. Chuanqilong shows many similarities with Liaoningosaurus and may represent a later ontogenetic stage of the taxon.

Zhongjianosaurus is a genus of dromaeosaurid belonging to the Microraptoria. Believed to hail from the Yixian Formation, specifically the middle of the Jehol Biota, it is the smallest known microraptorine thus far discovered and one of the smallest non-avian theropod dinosaurs.

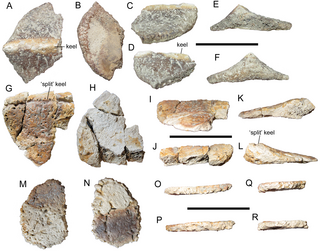

Akainacephalus is a monospecific genus of ankylosaurid dinosaur from southern Utah that lived during the Late Cretaceous in what is now the Horse Mountain Gryposaur Quarry of the Kaiparowits Formation. The type and only species, Akainacephalus johnsoni, is known from the most complete ankylosaur specimen ever discovered from southern Laramidia, including a complete skull, tail club, a number of osteoderms, limb elements and part of its pelvis, among other remains. It was described in 2018 by Jelle P. Wiersma and Randall B. Irmis. It is closely related and shares similar cranial anatomy to Nodocephalosaurus.

Invictarx is a monospecific genus of nodosaurid dinosaur from New Mexico that lived during the Late Cretaceous in what is now the upper Allison Member of the Menefee Formation. The type and only species, Invictarx zephyri, is known from three isolated, incomplete postcranial skeletons. It was named in 2018 by Andrew T. McDonald and Douglas G. Wolfe. Invictarx shares similarities with Glyptodontopelta from the Naashoibito member of the Ojo Alamo Formation, New Mexico.

Dynamoterror is a monospecific genus of tyrannosaurid dinosaur from New Mexico that lived during the Late Cretaceous in what is now the upper Allison Member of the Menefee Formation. The type and only species, Dynamoterror dynastes, is known from a subadult or adult individual about 9 metres long with an incomplete associated skeleton. It was named in 2018 by Andrew T. McDonald, Douglas G. Wolfe and Alton C. Dooley, Jr. Dynamoterror was closely related to Teratophoneus and Lythronax.