Related Research Articles

Pierre Huyghe is a French contemporary artist, who works in a variety of media from films and sculptures to public interventions and living systems. He lives and works in Paris and New York.

Nicolas Bourriaud is a French curator and art critic, who has curated a great number of exhibitions and biennials all over the world.

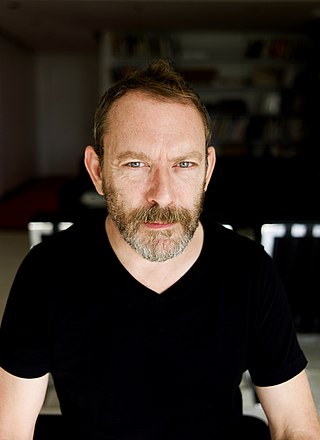

Liam Gillick is a British artist who lives and works in New York City. Gillick deploys multiple forms to make visible the aesthetics of the constructed world and examine the ideological control systems that have emerged along with globalization and neoliberalism. He utilizes materials that resemble everyday built environments, transforming them into minimalist abstractions that deliver commentaries on social constructs, while also exploring notions of modernism.

Christopher Sperandio is an American artist known for his collaborative work with British artist Simon Grennan.

In art, institutional critique is the systematic inquiry into the workings of art institutions, such as galleries and museums, and is most associated with the work of artists like Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, Andrea Fraser, John Knight (artist), Adrian Piper, Fred Wilson, and Hans Haacke and the scholarship of Alexander Alberro, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Birgit Pelzer, and Anne Rorimer.

Rirkrit Tiravanija is a Thai contemporary artist residing in New York City, Berlin, and Chiangmai, Thailand. He was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1961. His installations often take the form of stages or rooms for sharing meals, cooking, reading or playing music; architecture or structures for living and socializing are a core element in his work.

Matthieu Laurette is a media and conceptual contemporary French artist who works in a variety of media, from TV and video to installation and public interventions.

Miltos Manetas is a Greek painter and multimedia artist. He currently lives and works in Bogotá.

Henry Bond, FHEA is an English writer, photographer, and visual artist. In his Lacan at the Scene (2009), Bond made contributions to theoretical psychoanalysis and forensics.

Traffic is the title of a group exhibition of contemporary art that took place at CAPC musée d'art contemporain de Bordeaux, France, through February and March, 1996.

Walead Beshty is a Los Angeles–based artist and writer.

Air de Paris is a contemporary art gallery owned and directed by Florence Bonnefous and Edouard Merino, now located in Romainville, France.

Aperto ’93 is the title of an exhibition of contemporary art conceived by Helena Kontova and Giancarlo Politi, and organized by Helena Kontova for the XLV edition of the Venice Biennale, directed by Achille Bonito Oliva in 1993. It reprised and expanded the concept of the exhibition Aperto, a new section in the Biennale for young artists ideated by Bonito Oliva and Harald Szeemann in 1980.

The term Context art was introduced through the seminal exhibition and an accompanying publication Kontext Kunst. The Art of the 90s curated by Peter Weibel at the Neue Galerie im Künstlerhaus Graz (Austria) in 1993 (02.10.–07.11.1993).

Claire Bishop is a British art historian, critic, and Professor of Art History at CUNY Graduate Center, New York where she has taught since September 2008.

Michael Lin is a Taiwanese artist who lives and works in Brussels, Belgium and Taipei, Taiwan. He was born in Tokyo, Japan, and grew up in Taiwan and the United States. Lin is considered a leading Taiwanese contemporary painter and conceptual artist.

Social practice or socially engaged practice in the arts focuses on community engagement through a range of art media, human interaction and social discourse. While the term social practice has been used in the social sciences to refer to a fundamental property of human interaction, it has also been used to describe community-based arts practices such as relational aesthetics, new genre public art, socially engaged art, dialogical art, participatory art, and ecosocial immersionism.

Joseph Grigely is an American visual artist and scholar. His work is primarily conceptual and engages a variety of media forms including sculpture, video, and installations. Grigely was included in two Whitney Biennials, and is also a Guggenheim Fellow. He lives and works in Chicago, where he is Professor of Visual and Critical Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The CCS Hessel Museum of Art is an art museum located on the campus of Bard College, in Annandale-On-Hudson, New York. The museum was built in 2006. The Hessel Museum is housed in the Center for Curatorial Studies (CCS). The Museum draws from the Marieluise Hessel Collection of Contemporary Art, which comprises more than 1,700 objects on permanent loan to Bard. The Hessel Museum activates the collection for research, teaching and learning for students, faculty and the general public through exhibitions, publications, public programs, and events – on site and through digital resources.

Barbara Steiner is an Austrian art historian, curator, author, and editor. Steiner is the director of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. She served as the director of the Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig from 2001 to 2011, and as the director of Kunsthaus Graz from 2016 to 2021.

References

- ↑ Bourriaud, Nicolas, Relational Aesthetics p.113

- ↑ "PLACE Program". Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ↑ "BOILER - context". Archived from the original on 2008-05-22. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ↑ As a term, "relational art" has become accepted over "relational aesthetics" by the art world and Bourriaud himself as indicated by the 2002 exhibition Touch: Relational Art from the 1990s to Now at San Francisco Art Institute, curated by Bourriaud.

- ↑ "PLACE Program". Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ↑ Simpson, Bennett. "Public Relations: Nicolas Bourriaud Interview."

- ↑ Bishop, Claire. "Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics", pp. 54-55

- ↑ Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics, pp. 46-48

- ↑ Bourriaud, Nicolas. Traffic, Catalogue Capc Bordeaux, 1996

- ↑ "TRAFFIC CONTROL". www.mutualart.com.

- ↑ Bourriaud p. 7

- ↑ Bishop p. 54

- ↑ Bourriaud, Nicolas, Caroline Schneider and Jeanine Herman. Postproduction: Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World, p. 8

- ↑ Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics p. 113

- ↑ Bourriaud p. 13

- ↑ Stam, Robert (2015). Keywords in Subversive Film / Media Aesthetics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 282. ISBN 978-1118340615.

- ↑ Bourriaud pp. 17-18

- ↑ "BBC iPlayer - BBC Four". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ Bishop p.52

- ↑ Bishop p.53

- ↑ Bishop p.53.

- ↑ Bishop p.52

- ↑ Bishop, p.65

- ↑ Bishop p.67

- ↑ "Features | Nicolas Bourriaud and Karen Moss". Stretcher.org. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ Cobb, Chris (2002-12-14). "Features | Touch - Relational Art from the 1990s to Now". Stretcher.org. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ "theanyspacewhatever". web.guggenheim.org.