| Hippidion | |

|---|---|

| |

| H. principale skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Subfamily: | Equinae |

| Tribe: | Equini |

| Genus: | † Hippidion Owen, 1869 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

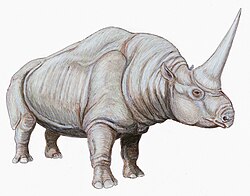

Hippidion (meaning "little horse" in Ancient Greek) is an extinct genus of equine that lived in South America from the Late Pliocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene (Lujanian), between 2.5 million and 11,000 years ago. Hippidion arrived in South America along with many other animals of North American origin as part of the Great American Interchange. They were one of two lineages of equines native to South America during the Pleistocene epoch, alongside Equus (Amerhippus) neogeus . Hippidion ranged widely over South America, extending to the far south of Patagonia. Hippidion differs from living equines of the genus Equus in having a long notch separating the nasal bone from the rest of the skull, which may indicate the presence of a prehensile upper lip.

Contents

- Taxonomy

- Evolution

- Description

- Paleobiology

- Distribution

- Relationship with humans and extinction

- References

Hippidion became extinct as part of the end-Pleistocene extinction event around 12-11,000 years ago, along with most other large animals native to the Americas. Remains of Hippidion dating to shortly before its extinction have been found with cut marks and associated with human artifacts, such as stone Fishtail points, which may suggest that hunting by recently arrived humans may have been a factor in its extinction.