Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, was the movement to end slavery. This term can be used both formally and informally. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and set slaves free. King Charles I of Spain, usually known as Emperor Charles V, was following the example of Louis X of France, who had abolished slavery within the Kingdom of France in 1315. He passed a law which would have abolished colonial slavery in 1542, although this law was not passed in the largest colonial states, and it was not enforced as a result. In the late 17th century, the Roman Catholic Church officially condemned the slave trade in response to a plea by Lourenço da Silva de Mendouça, and it was also vehemently condemned by Pope Gregory XVI in 1839. The abolitionist movement only started in the late 18th century, however, when English and American Quakers began to question the morality of slavery. James Oglethorpe was among the first to articulate the Enlightenment case against slavery, banning it in the Province of Georgia on humanitarian grounds, and arguing against it in Parliament, and eventually encouraging his friends Granville Sharp and Hannah More to vigorously pursue the cause. Soon after his death in 1785, Sharp and More united with William Wilberforce and others in forming the Clapham Sect.

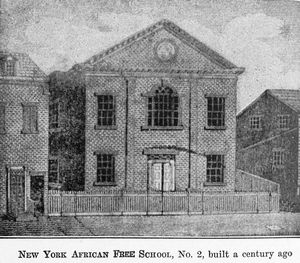

Slavery in the colonial history of the United States, from 1600 to 1776, developed from complex factors, and researchers have proposed several theories to explain the development of the institution of slavery and of the slave trade. Slavery strongly correlated with Europe's American colonies' need for labor, especially for the labor-intensive plantation economies of the sugar colonies in the Caribbean, operated by Great Britain, France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic.

Slavery in the United States was the legal institution of human chattel enslavement, primarily of Africans and African Americans, that existed in the United States of America from the beginning of the nation in 1776 until passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Slavery had been practiced in British America from early colonial days, and was legal in all thirteen colonies at the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property and could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until 1865. As an economic system, slavery was largely replaced by sharecropping and convict leasing.

In United States history, a free Negro or free black was the legal status, in the geographic area of the United States, of blacks who were not slaves. It included both freed slaves (freedmen) and those who had been born free.

African Burial Ground National Monument is a monument at Duane Street and African Burial Ground Way in the Civic Center section of Lower Manhattan, New York City. Its main building is the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway. The site contains the remains of more than 419 Africans buried during the late 17th and 18th centuries in a portion of what was the largest colonial-era cemetery for people of African descent, some free, most enslaved. Historians estimate there may have been as many as 10,000–20,000 burials in what was called the "Negroes Burial Ground" in the 1700s. The five to six acre site's excavation and study was called "the most important historic urban archaeological project in the United States." The Burial Ground site is New York's earliest known African-American "cemetery"; studies show an estimated 15,000 African American people were buried here.

Freedom's Journal was the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States. Founded by Rev. John Wilk and other free black men in New York City, it was published weekly starting with the 16 March 1827 issue. Freedom's Journal was superseded in 1829 by The Rights of All, published between 1829 and 1830 by Samuel Cornish, the former senior editor of the Journal.

The New York Slave Revolt of 1712 was an uprising in New York City, in the British Province of New York, of 23 enslaved Africans. They killed nine whites and injured another six before they were stopped. More than three times that number of blacks, 70, were arrested and jailed. Of these, 27 were put on trial, and 21 convicted and executed.

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was a British abolitionist group, formed on 22 May 1787, by twelve men who gathered together at a printing shop in London. The Society worked to educate the public about the abuses of the slave trade; it achieved abolition of the international slave trade in 1807, enforced by the Royal Navy. The United States also prohibited the African slave trade that year, to take effect in 1808.

Slavery in New Jersey began in the early 17th century, when Dutch colonists imported African slaves for labor to develop their colony of New Netherland. After England took control of the colony in 1664, its colonists continued the importation of slaves from Africa. They also imported "seasoned" slaves from their colonies in the West Indies and enslaved Native Americans from the Carolinas.

The New-York Manumission Society was an American organization founded in 1785 by U.S. Founding Father John Jay, among others, to promote the gradual abolition of slavery and manumission of slaves of African descent within the state of New York. The organization was made up entirely of white men, most of whom were wealthy and held influential positions in society. Throughout its history, which ended in 1849 after the abolition of slavery in New York, the society battled against the slave trade, and for the eventual emancipation of all the slaves in the state. It founded the African Free School for the poor and orphaned children of slaves and free people of color.

The African Free School was a school for children of slaves and free people of color in New York City. It was founded by members of the New York Manumission Society, including Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, on November 2, 1787. Many of its alumni became leaders in the African-American community in New York.

Atlantic Creole is a term used in North America to describe a mixed-race ethnic group of Americans who have ancestral roots in Africa, Europe and sometimes the Caribbean. These people are culturally American and are the descendants of a Charter Generation of slaves and indentured workers during the European colonization of the Americas before 1660. Some had lived and worked in Europe or the Caribbean before coming to North America. Examples of such men included John Punch and Emanuel Driggus.

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed either by manumission or emancipation. A fugitive slave is a person who escaped slavery by fleeing.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported African slaves for workers; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Slavery was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled Pennsylvania tolerated slavery, but the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Slavery in Maryland lasted around 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined here as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as their economy improved at home, fewer made passage to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

Slavery in Virginia dates to 1619, soon after the founding of Virginia as an English colony by the London Virginia Company. The company established a headright system to encourage colonists to transport indentured servants to the colony for labor; they received a certain amount of land for people whose passage they paid to Virginia.

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by enslaved people against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

John Punch was an enslaved African who lived in the Colony of Virginia. Thought to have been an indentured servant, Punch attempted to escape to Maryland and was sentenced in July 1640 by the Virginia Governor's Council to serve as a slave for the remainder of his life. Two European men who ran away with him received a lighter sentence of extended indentured servitude. For this reason, historians consider John Punch the "first official slave in the English colonies," and his case as the "first legal sanctioning of lifelong slavery in the Chesapeake." Historians also consider this to be one of the first legal distinctions between Europeans and Africans made in the colony, and a key milestone in the development of the institution of slavery in the United States.

Dorothy Creole was one of the first black women to arrive in New York. She arrived in 1627. That year, three enslaved African women set foot on the southern shore of Manhattan, arriving in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Property of the Dutch West India Company, these women were brought to the colony to become the wives of enslaved African men who had arrived in 1625. One of these women was named Dorothy Creole, a surname that she acquired in the New World, and likely began as a descriptive term.

Slavery was legally practiced in the Province of North Carolina and the state of North Carolina until January 1, 1863 when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Prior to statehood, there were 41,000 enslaved African-Americans in the Province of North Carolina in 1767. By 1860, the number of slaves in the state of North Carolina was 331,059, about one third of the total population of the state. In 1860, there were nineteen counties in North Carolina where the number of slaves was larger than the free white population. During the antebellum period the state of North Carolina passed several laws to protect the rights of slave owners while disenfranchising the rights of slaves. There was a constant fear amongst white slave owners in North Carolina of slave revolts from the time of the American Revolution. Despite their circumstances, some North Carolina slaves and freed slaves distinguished themselves as artisans, soldiers during the Revolution, religious leaders, and writers.

![Jacob van Meurs, Novum Amsterodamum [New Amsterdam], 1671. In the centre of the picture a man is depicted hanging by his middle, suspended by a hook in his ribs and swung to and fro. AMH-6831-KB View of New Amsterdam.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5f/AMH-6831-KB_View_of_New_Amsterdam.jpg/440px-AMH-6831-KB_View_of_New_Amsterdam.jpg)