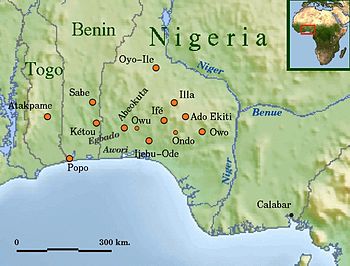

The Kingdom of Dahomey was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. It developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a regional power in the 18th century by expanding south to conquer key cities like Whydah belonging to the Kingdom of Whydah on the Atlantic coast which granted it unhindered access to the tricontinental Atlantic Slave Trade.

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Passage. Europeans established a coastal slave trade in the 15th century and trade to the Americas began in the 16th century, lasting through the 19th century. The vast majority of those who were transported in the transatlantic slave trade were from Central Africa and West Africa and had been sold by West African slave traders to European slave traders, while others had been captured directly by the slave traders in coastal raids. European slave traders gathered and imprisoned the enslaved at forts on the African coast and then brought them to the Americas. Some Portuguese and Europeans participated in slave raids. As the National Museums Liverpool explains: "European traders captured some Africans in raids along the coast, but bought most of them from local African or African-European dealers." Many European slave traders generally did not participate in slave raids because life expectancy for Europeans in sub-Saharan Africa was less than one year during the period of the slave trade because of malaria that was endemic in the African continent. An article from PBS explains: "Malaria, dysentery, yellow fever, and other diseases reduced the few Europeans living and trading along the West African coast to a chronic state of ill health and earned Africa the name 'white man's grave.' In this environment, European merchants were rarely in a position to call the shots." The earliest known use of the phrase began in the 1830s, and the earliest written evidence was found in an 1836 published book by F. H. Rankin. Portuguese coastal raiders found that slave raiding was too costly and often ineffective and opted for established commercial relations.

Agaja was a king of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, who ruled from 1718 until 1740. He came to the throne after his brother King Akaba. During his reign, Dahomey expanded significantly and took control of key trade routes for the Atlantic slave trade by conquering Allada (1724) and Whydah (1727). Wars with the powerful Oyo Empire to the east of Dahomey resulted in Agaja accepting tributary status to that empire and providing yearly gifts. After this, Agaja attempted to control the new territory of the kingdom of Dahomey through militarily suppressing revolts and creating administrative and ceremonial systems. Agaja died in 1740 after another war with the Oyo Empire and his son Tegbessou became the new king. Agaja is credited with creating many of the key government structures of Dahomey, including the Yovogan and the Mehu.

Tegbesu or Bossa Ahadee was a king of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, from 1740 until 1774. While not the oldest son of King Agaja (1718-1740), he became king after Agaja's death following a succession struggle with a brother.

Kpengla was a King of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, from 1774 until 1789. Kpengla followed his father Tegbessou to the throne and much of his administration was defined by the increasing Atlantic slave trade and regional rivalry over the profits from this trade. His attempts to control the slave trade generally failed, and when he died of smallpox in 1789, his son Agonglo came to the throne and ended many of his policies.

Agonglo was a King of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, from 1789 until 1797. Agonglo took over from his father King Kpengla in 1789 and inherited many of the economic problems that developed during Kpengla's reign. Because of the poor economy, Agonglo was often constrained by domestic opposition. As a response, he reformed many of the economic policies and did military expeditions to try to increase the supply for the Atlantic slave trade. Many of these efforts were unsuccessful and European traders became less active in the ports of the kingdom. As a final effort, Agonglo accepted two Portuguese Catholic missionaries which resulted in a large outcry in royal circles and resulted in his assassination on May 1, 1797. Adandozan, his second oldest son, was named the new king.

Adandozan was a king of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, from 1797 until 1818. His rule ended with a coup by his brother Ghezo who then erased Adandozan from the official history resulting in high uncertainty about many aspects of his life. Adandozan took over from his father Agonglo in 1797 but was quite young at the time and so there was a regent in charge of the kingdom until 1804. Dealing with the economic depression that had defined the administrations of his father Agonglo and grandfather Kpengla, Adandozan tried to reduce slavery to decrease European trade, and when these failed reform the economy to focus on agriculture. Unfortunately, these efforts did not end domestic dissent and in 1818 at the Annual Customs of Dahomey, Ghezo and Francisco Félix de Sousa, a powerful Brazilian slave trader, organized a coup d'état and replaced Adandozan. He was left alive and lived until the 1860s hidden in the palaces while he was largely erased from official royal history.

Ghezo, also spelled Gezo, was King of Dahomey from 1818 until 1858. Ghezo replaced his brother Adandozan as king through a coup with the assistance of the Brazilian slave trader Francisco Félix de Sousa. He ruled over the kingdom during a tumultuous period, punctuated by the British blockade of the ports of Dahomey in order to stop the Atlantic slave trade.

The Fon people, also called Dahomeans, Fon nu or Agadja are a Gbe ethnic group. They are the largest ethnic group in Benin, found particularly in its south region; they are also found in southwest Nigeria and Togo. Their total population is estimated to be about 3,500,000 people, and they speak the Fon language, a member of the Gbe languages.

The Royal African Company (RAC) was an English trading company established in 1660 by the House of Stuart and City of London merchants to trade along the West African coast. It was overseen by the Duke of York, the brother of Charles II of England; the RAC was founded after Charles II ascended to the English throne in the 1660 Stuart Restoration, and he granted it a monopoly on all English trade with Africa. While the company's original purpose was to trade for gold in the Gambia River, as Prince Rupert of the Rhine had identified gold deposits in the region during the Interregnum, the RAC quickly began trading in slaves, which became its largest commodity.

Ouidah or Whydah, and known locally as Glexwe, formerly the chief port of the Kingdom of Whydah, is a city on the coast of the Republic of Benin. The commune covers an area of 364 km2 (141 sq mi) and as of 2002 had a population of 76,555 people.

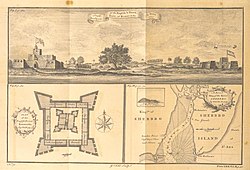

The Forte de São João Baptista de Ajudá is a small restored fort in Ouidah, Benin. Built in 1721, it was the last of three European forts built in that town to tap the slave trade of the Slave Coast. Following the legal abolition of the slave trade early in the 19th century, the Portuguese fort lay abandoned most of the time until it was permanently reoccupied in 1865.

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were once commonplace in parts of Africa, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient and medieval world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Red Sea slave trade, Indian Ocean slave trade and Atlantic slave trade began, many of the pre-existing local African slave systems began supplying captives for slave markets outside Africa. Slavery in contemporary Africa is still practised despite it being illegal.

The Kingdom of Whydah ( known locally as; Glexwe / Glehoue, but also known and spelt in old literature as; Hueda, Whidah,Ajuda, Ouidah, Whidaw,Juida, and Juda was a kingdom on the coast of West Africa in what is now Benin. It was a major slave trading area which exported more than one million Africans to the United States, the Caribbean and Brazil before closing its trade in the 1860s. In 1700, it had a coastline of around 16 kilometres ; under King Haffon, this was expanded to 64 km, and stretching 40 km inland.

Savi is a town in Benin that was the capital of the Kingdom of Whydah prior to its capture by the forces of Dahomey in 1727.

The Dutch Slave Coast refers to the trading posts of the Dutch West India Company on the Slave Coast, which lie in contemporary Ghana, Benin, Togo, and Nigeria. The primary purpose of the trading post was to supply slaves for the Dutch colonies in the Americas. Dutch involvement on the Slave Coast started with the establishment of a trading post in Offra in 1660. Later, trade shifted to Ouidah, where the English and French also had a trading post. Political unrest caused the Dutch to abandon their trading post at Ouidah in 1725, now moving to Jaquim, at which place they built Fort Zeelandia. By 1760, the Dutch had abandoned their last trading post in the region.

The History of the Kingdom of Dahomey spans 400 years from around 1600 until 1904 with the rise of the Kingdom of Dahomey as a major power on the Atlantic coast of modern-day Benin until French conquest. The kingdom became a major regional power in the 1720s when it conquered the coastal kingdoms of Allada and Whydah. With control over these key coastal cities, Dahomey became a major center in the Atlantic Slave Trade until 1852 when the British imposed a naval blockade to stop the trade. War with the French began in 1892 and the French took over the Kingdom of Dahomey in 1894. The throne was vacated by the French in 1900, but the royal families and key administrative positions of the administration continued to have a large impact in the politics of the French administration and the post-independence Republic of Dahomey, renamed Benin in 1975. Historiography of the kingdom has had a significant impact on work far beyond African history and the history of the kingdom forms the backdrop for a number of novels and plays.

The Komenda Wars were a series of wars from 1694 until 1700 largely between the Dutch West India Company and the English Royal African Company in the Eguafo Kingdom in the present day state of Ghana, over trade rights. The Dutch were trying to keep the English out of the region to maintain a trade monopoly, while the English were attempting to re-establish a fort in the city of Komenda. The fighting included forces of the Dutch West India Company, the Royal African Company, the Eguafo Kingdom, a prince of the kingdom attempting to rise to the throne, the forces of a powerful merchant named John Cabess, other Akan tribes and kingdoms like Twifo and Denkyira. There were four separate periods of warfare, including a civil war in the Eguafo Kingdom, and the wars ended with the English placing Takyi Kuma into power in Eguafo. Because of the rapidly shifting alliances between European and African powers, historian John Thornton has found that "there is no finer example of [the] complicated combination of European rivalry merging with African rivalry than the Komenda Wars."

John Cabess was a prominent African trader in the port city of Komenda, part of the Eguafo Kingdom, in modern-day Ghana. He was a major British ally and was a supplier to the British Royal African Company. As a trader, he became a strong economic and political force in the coastal region in the early 1700s, playing an active role in the Komenda Wars, the rise of the Ashanti Empire, the expansion of British involvement in West Africa, and the beginnings of large-scale Atlantic slave trade. Because of his combined economic and political power, historian Kwame Daaku named Cabess one of the "merchant princes" of the Gold Coast in the 1700s. He died in 1722, but his heirs continued to exert economic power in the port for the remainder of the 18th century.

The Kingdom of Ardra, also known as the Kingdom of Allada, was a coastal West African kingdom in southern Benin. While historically a sovereign kingdom, in present times the monarchy continues to exist as a non-sovereign monarchy within the republic of Benin.