Antiviral drugs are a class of medication used for treating viral infections. Most antivirals target specific viruses, while a broad-spectrum antiviral is effective against a wide range of viruses. Antiviral drugs are a class of antimicrobials, a larger group which also includes antibiotic, antifungal and antiparasitic drugs, or antiviral drugs based on monoclonal antibodies. Most antivirals are considered relatively harmless to the host, and therefore can be used to treat infections. They should be distinguished from virucides, which are not medication but deactivate or destroy virus particles, either inside or outside the body. Natural virucides are produced by some plants such as eucalyptus and Australian tea trees.

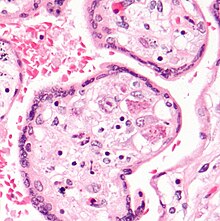

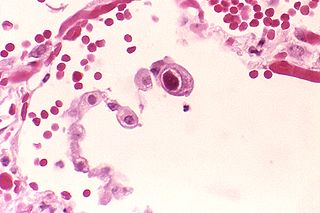

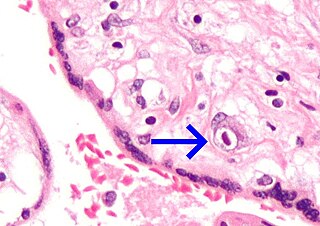

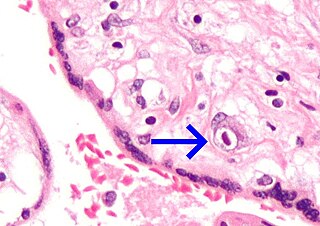

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a genus of viruses in the order Herpesvirales, in the family Herpesviridae, in the subfamily Betaherpesvirinae. Humans and other primates serve as natural hosts. The 11 species in this genus include human betaherpesvirus 5, which is the species that infects humans. Diseases associated with HHV-5 include mononucleosis and pneumonia, and congenital CMV in infants can lead to deafness and ambulatory problems.

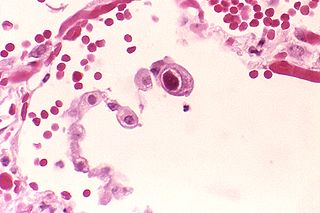

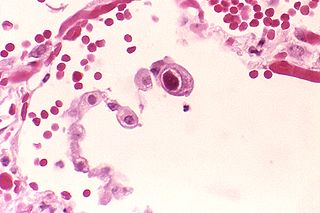

Infectious mononucleosis, also known as glandular fever, is an infection usually caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). Most people are infected by the virus as children, when the disease produces few or no symptoms. In young adults, the disease often results in fever, sore throat, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, and fatigue. Most people recover in two to four weeks; however, feeling tired may last for months. The liver or spleen may also become swollen, and in less than one percent of cases splenic rupture may occur.

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is one of the nine known human herpesvirus types in the herpes family, and is one of the most common viruses in humans. EBV is a double-stranded DNA virus. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is the first identified oncogenic virus, or a virus that can cause cancer. EBV establishes permanent infection in humans. It causes infectious mononucleosis and is also tightly linked to many malignant diseases (cancers). Various vaccine formulations underwent testing in different animals or in humans. However, none of them were able to prevent EBV infection and no vaccine has been approved to date.

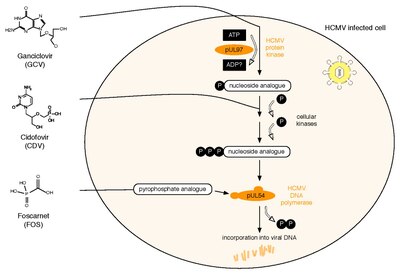

Ganciclovir, sold under the brand name Cytovene among others, is an antiviral medication used to treat cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections.

Valganciclovir, sold under the brand name Valcyte among others, is an antiviral medication used to treat cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in those with HIV/AIDS or following organ transplant. It is often used long term as it only suppresses rather than cures the infection. Valganciclovir is taken by mouth.

Cytomegalovirus retinitis, also known as CMV retinitis, is an inflammation of the retina of the eye that can lead to blindness. Caused by human cytomegalovirus, it occurs predominantly in people whose immune system has been compromised, including 15-40% of those with AIDS.

Herpesviridae is a large family of DNA viruses that cause infections and certain diseases in animals, including humans. The members of this family are also known as herpesviruses. The family name is derived from the Greek word ἕρπειν, referring to spreading cutaneous lesions, usually involving blisters, seen in flares of herpes simplex 1, herpes simplex 2 and herpes zoster (shingles). In 1971, the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) established Herpesvirus as a genus with 23 viruses among four groups. As of 2020, 115 species are recognized, all but one of which are in one of the three subfamilies. Herpesviruses can cause both latent and lytic infections.

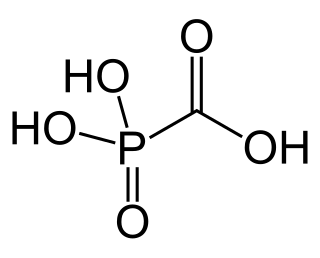

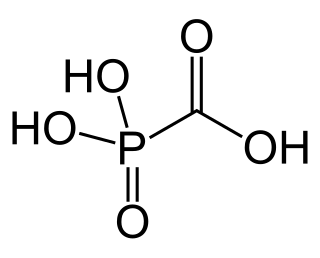

Foscarnet (phosphonomethanoic acid), known by its brand name Foscavir, is an antiviral medication which is primarily used to treat viral infections involving the Herpesviridae family. It is classified as a pyrophosphate analog DNA polymerase inhibitor. Foscarnet is the conjugate base of a chemical compound with the formula HO2CPO3H2 (Trisodium phosphonoformate).

Betaherpesvirinae is a subfamily of viruses in the order Herpesvirales and in the family Herpesviridae. Mammals serve as natural hosts. There are 26 species in this subfamily, divided among 5 genera. Diseases associated with this subfamily include: human cytomegalovirus (HHV-5): congenital CMV infection; HHV-6: 'sixth disease' ; HHV-7: symptoms analogous to the 'sixth disease'.

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms begin one to four days after exposure to the virus and last for about two to eight days. Diarrhea and vomiting can occur, particularly in children. Influenza may progress to pneumonia from the virus or a subsequent bacterial infection. Other complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome, meningitis, encephalitis, and worsening of pre-existing health problems such as asthma and cardiovascular disease.

A Cytomegalovirus vaccine is a vaccine to prevent cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection or curb virus re-activation in persons already infected. Challenges in developing a vaccine include adeptness of CMV in evading the immune system and limited animal models. As of 2018 no such vaccine exists, although a number of vaccine candidates are under investigation. They include recombinant protein, live attenuated, DNA and other vaccines.

As of 2024, a vaccine against Epstein–Barr virus was not yet available. The virus establishes latent infection and causes infectious mononucleosis. There is also increasingly more evidence that EBV may be a trigger of multiple sclerosis. It is a dual-tropic virus, meaning that it infects two different host cell types — in this case, both B cells and epithelial cells. One challenge is that the Epstein–Barr virus expresses very different proteins during its lytic and its latent phases. Antiviral agents act by inhibiting viral DNA replication, but as of 2016, there was little evidence that they are effective against Epstein–Barr virus. They are also expensive, risk causing resistance to antiviral agents, and can cause unpleasant side effects.

Maribavir, sold under the brand name Livtencity, is an antiviral medication that is used to treat post-transplant cytomegalovirus (CMV). Maribavir is a cytomegalovirus pUL97 kinase inhibitor that works by preventing the activity of human cytomegalovirus enzyme pUL97, thus blocking virus replication.

Human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7) is one of nine known members of the Herpesviridae family that infects humans. HHV-7 is a member of Betaherpesvirinae, a subfamily of the Herpesviridae that also includes HHV-6 and Cytomegalovirus. HHV-7 often acts together with HHV-6, and the viruses together are sometimes referred to by their genus, Roseolovirus. HHV-7 was first isolated in 1990 from CD4+ T cells taken from peripheral blood lymphocytes.

A neutralizing antibody (NAb) is an antibody that defends a cell from a pathogen or infectious particle by neutralizing any effect it has biologically. Neutralization renders the particle no longer infectious or pathogenic. Neutralizing antibodies are part of the humoral response of the adaptive immune system against viruses, bacteria and microbial toxin. By binding specifically to surface structures (antigen) on an infectious particle, neutralizing antibodies prevent the particle from interacting with its host cells it might infect and destroy.

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in a newborn baby. Most have no symptoms. Some affected babies are small. Other signs and symptoms include a rash, jaundice, hepatomegaly, retinitis, and seizures. It may lead to loss of hearing or vision, developmental disability, or a small head.

Cytomegalovirus colitis is an inflammation of the colon.

Letermovir is an antiviral drug for the treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections. It has been tested in CMV infected patients with allogeneic stem cell transplants and may also be useful for other patients with a compromised immune system such as those with organ transplants or HIV infections. The drug was initially developed by the anti-infective division at Bayer, which became AiCuris Anti-infective Cures AG through a spin-out and progressed the development to end of Phase 2 before the project was sold to Merck & Co for Phase 3 development and approval.

Amos Panet is a distinguished Professor of Virology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research has focused on virology and biotechnology.