A knot is an intentional complication in cordage which may be practical or decorative, or both. Practical knots are classified by function, including hitches, bends, loop knots, and splices: a hitch fastens a rope to another object; a bend fastens two ends of a rope to each another; a loop knot is any knot creating a loop; and splice denotes any multi-strand knot, including bends and loops. A knot may also refer, in the strictest sense, to a stopper or knob at the end of a rope to keep that end from slipping through a grommet or eye. Knots have excited interest since ancient times for their practical uses, as well as their topological intricacy, studied in the area of mathematics known as knot theory.

A shank is a type of knot that is used to shorten a rope or take up slack, such as the sheepshank. The sheepshank knot is not stable. It will fall apart under too much load or too little load.

The figure-eight knot or figure-of-eight knot is a type of stopper knot. It is very important in both sailing and rock climbing as a method of stopping ropes from running out of retaining devices. Like the overhand knot, which will jam under strain, often requiring the rope to be cut, the figure-eight will also jam, but is usually more easily undone than the overhand knot.

The figure-eight or figure-of-eight knot is also called the Flemish knot. The name figure-of-eight knot appears in Lever's Sheet Anchor; or, a Key to Rigging. The word "of" is nowadays usually omitted. The knot is the sailor's common single-strand stopper knot and is tied in the ends of tackle falls and running rigging, unless the latter is fitted with monkey's tails. It is used about ship wherever a temporary stopper knot is required. The figure-eight is much easier to untie than the overhand, it does not have the same tendency to jam and so injure the fiber, and is larger, stronger, and equally secure.

Figure-eight loop is a type of knot created by a loop on the bight. It is used in climbing and caving.

The Flemish loop or figure-eight loop is perhaps stronger than the loop knot. Neither of these knots is used at sea, as they are hard to untie. In hooking a tackle to any of the loops, if the loop is long enough it is better to arrange the rope as a cat's paw.

A zeppelin bend is an end-to-end joining knot formed by two symmetrically interlinked overhand knots. It is stable, secure, and highly resistant to jamming. It is also resistant to the effects of slack shaking and cyclic loading.

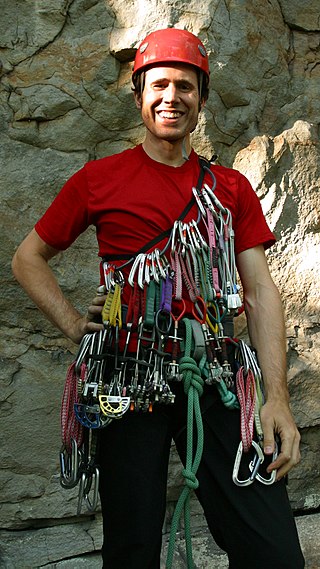

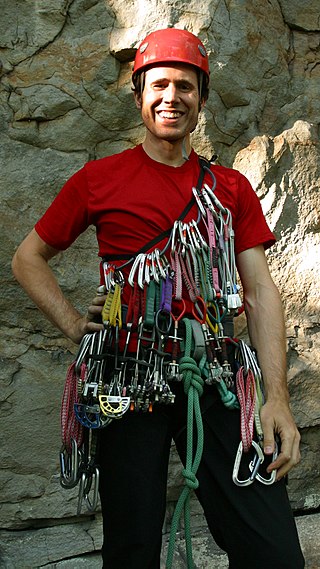

A climbing harness is a device which allows a climber access to the safety of a rope. It is used in rock and ice climbing, abseiling, and lowering; this is in contrast to other activities requiring ropes for access or safety such as industrial rope work, construction, and rescue and recovery, which use safety harnesses instead.

Glossary of climbing terms relates to rock climbing, mountaineering, and to ice climbing.

Rock-climbing equipment requires a range of specialized sports equipment, for training, for aid climbing, and for free climbing. Developments in rock-climbing equipment played an important role in the history of rock climbing, enabling climbers to ascend more difficult climbing routes safely, and materially improving the strength, conditioning, and ability of climbers.

Abseiling, also known as rappelling, is the controlled descent of a steep slope, such as a rock face, by moving down a rope. When abseiling, the person descending controls their own movement down the rope, in contrast to lowering off, in which the rope attached to the person descending is paid out by their belayer.

The sheet bend is a bend. It is practical for joining lines of different diameter or rigidity.

The Munter hitch, also known as the Italian hitch, mezzo barcaiolo or the crossing hitch, is a simple adjustable knot, commonly used by climbers, cavers, and rescuers to control friction in a life-lining or belay system. To climbers, this hitch is also known as HMS, the abbreviation for the German term Halbmastwurfsicherung, meaning half clove hitch belay. This technique can be used with a special "pear-shaped" HMS locking carabiner, or any locking carabiner wide enough to take two turns of the rope.

Kernmantle rope is rope constructed with its interior core protected by a woven exterior sheath designed to optimize strength, durability, and flexibility. The core fibers provide the tensile strength of the rope, while the sheath protects the core from abrasion during use. This is the only construction of rope that is considered to be life safety rope by most fire and rescue services.

The water knot is a knot frequently used in climbing for joining two ends of webbing together, for instance when making a sling.

A Prusik is a friction hitch or knot used to attach a loop of cord around a rope, applied in climbing, canyoneering, mountaineering, caving, rope rescue, ziplining, and by arborists. The term Prusik is a name for both the loops of cord used to tie the hitch and the hitch itself, and the verb is "to prusik". More casually, the term is used for any friction hitch or device that can grab a rope. Due to the pronunciation, the word is often misspelled Prussik, Prussick, or Prussic.

A Yosemite bowline is a loop knot often perceived as having better security than a bowline. If the knot is not dressed correctly, it can potentially collapse into a noose, however testing reveals this alternative configuration to be strong and safe as a climbing tie-in.

A dynamic rope is a specially constructed, somewhat elastic rope used primarily in rock climbing, ice climbing, and mountaineering. This elasticity, or stretch, is the property that makes the rope dynamic—in contrast to a static rope that has only slight elongation under load. Greater elasticity allows a dynamic rope to more slowly absorb the energy of a sudden load, such from arresting a climber's fall, by reducing the peak force on the rope and thus the probability of the rope's catastrophic failure. A kernmantle rope is the most common type of dynamic rope now used. Since 1945, nylon has, because of its superior durability and strength, replaced all natural materials in climbing rope.

The South African Abseil or South African Double Roped Classical Abseil is a modern variation of the non-mechanical classical abseil method used by mountaineers and rock climbers to quickly descend steep terrain by sliding down a rope wrapped around their body to create controlled friction.

The offset figure-eight bend is a poor knot that has been implicated in the deaths of several rock climbers. The knot may capsize (invert) under load, as shown in the figure, and this can happen repeatedly. Each inversion reduces the lengths of the tails. Once the tails are used up completely, the knot comes undone.