Microorganisms

Obligate endosymbiotic bacteria

The genome of Nasuia deltocephalinicola , a symbiont of the European pest leafhopper, Macrosteles quadripunctulatus , consists of a circular chromosome of 112,031 base pairs. [1]

The genome of Nanoarchaeum equitans is 491 Kbp long. [2]

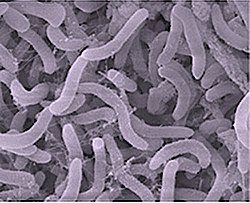

Pelagibacter ubique

Pelagibacter ubique is one of the smallest known free-living bacteria, with a length of 370 to 890 nm (0.00037 to 0.00089 mm) and an average cell diameter of 120 to 200 nm (0.00012 to 0.00020 mm). They also have the smallest free-living bacterium genome: 1.3 Mbp, 1354 protein genes, 35 RNA genes. They are one of the most common and smallest organisms in the ocean, with their total weight exceeding that of all fish in the sea. [3]

Mycoplasma genitalium

Mycoplasma genitalium , a parasitic bacterium which lives in the primate bladder, waste disposal organs, genital, and respiratory tracts, is thought to be the smallest known organism capable of independent growth and reproduction. With a size of approximately 200 to 300 nm, M. genitalium is an ultramicrobacterium, smaller than other small bacteria, including rickettsia and chlamydia. However, the vast majority of bacterial strains have not been studied, and the marine ultramicrobacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain RB2256 is reported to have passed through a 220 nm (0.00022 mm) ultrafilter. A complicating factor is nutrient-downsized bacteria, bacteria that become much smaller due to a lack of available nutrients. [4]

Nanoarchaeum

Nanoarchaeum equitans is a species of microbe 200 to 500 nm (0.00020 to 0.00050 mm) in diameter. It was discovered in 2002 in a hydrothermal vent off the coast of Iceland by Karl Stetter. A thermophile that grows in near-boiling temperatures, Nanoarchaeum appears to be an obligatory symbiont on the archaeon Ignicoccus ; it must be in contact with the host organism to survive. Guinness World Records recognizes Nanoarchaeum equitans as the smallest living organism. [5]

Single-celled eukaryotes (protists)

Prasinophyte algae of the genus Ostreococcus are the smallest free-living eukaryote. The single cell of an Ostreococcus measures 800 nm (0.00080 mm) across. [6]

Heliozoa

The Erebor lineage of Microheliella maris is the smallest known heliozoan with an average cell body diameter of 2.56 μm. [7]

Diatoms

The smallest diatoms with diameters as small as 1.9 μm can be found in the genera Mediolabrus and Minidiscus. [8] [9] Mediolabrus comicus is the smallest known marine diatom. [10]

Viruses

Some biologists consider viruses to be non-living because they lack a cellular structure and cannot metabolize or reproduce by themselves, requiring a host cell to replicate and synthesize new products. Some hold that, because viruses do have genetic material and can employ the metabolism of their host, they can be considered organisms. Also, an emerging concept that is gaining traction among some virologists is that of the virocell, in which the actual phenotype of a virus is the infected cell, and the virus particle (or virion) is merely a reproductive or dispersal stage, much like pollen or a spore. [11]

The smallest viruses in terms of genome size are single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses. Perhaps the most famous is the bacteriophage Phi-X174 with a genome size of 5,386 nucleotides. [12] However, some ssDNA viruses can be even smaller. For example, Porcine circovirus type 1 has a genome of 1,759 nucleotides [13] and a capsid diameter of 17 nm (1.7×10−5 mm). [14] As a whole, the viral family geminiviridae is about 30 nm (3.0×10−5 mm) in length. However, the two capsids making up the virus are fused; divided, the capsids would be 15 nm (1.5×10−5 mm) in length. Other environmentally characterized ssDNA viruses such as CRESS DNA viruses, among others, can have genomes that are considerably less than 2,000 nucleotides. [15] [16]

The smallest RNA virus in terms of genome size is phage BZ13 strain T72 at 3,393 nucleotides length. [17] Viruses using both DNA and RNA in their replication (retroviruses) range in size from 7,040 to 12,195 nucleotides. [18] The smallest double-stranded DNA viruses are the hepadnaviruses such as hepatitis B, at 3.2 kb and 42 nm (4.2×10−5 mm); parvoviruses have smaller capsids, at 18–26 nm (1.8×10−5–2.6×10−5 mm), but larger genomes, at 5 kb. It is important to consider other self-replicating genetic elements, such as obelisks, ribozymes, satelliviruses and viroids.[ citation needed ]