The insect order Neuroptera, or net-winged insects, includes the lacewings, mantidflies, antlions, and their relatives. The order consists of some 6,000 species. Neuroptera is grouped together with the Megaloptera and Raphidioptera (snakeflies) in the unranked taxon Neuropterida.

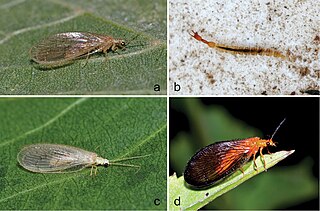

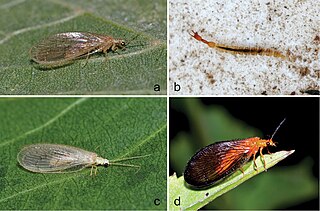

Megaloptera is an order of insects. It contains the alderflies, dobsonflies and fishflies, and there are about 300 known species.

Mantispidae, commonly known as mantidflies, mantispids, mantid lacewings, mantisflies or mantis-flies, is a family of small to moderate-sized insects in the order Neuroptera. There are many genera with around 400 species worldwide, especially in the tropics and subtropics. Only five species of Mantispa occur in Europe. As their names suggest, members of the group possess raptorial forelimbs similar to those of the praying mantis, a case of convergent evolution.

Osmylidae are a small family of winged insects of the net-winged insect order Neuroptera. The osmylids, also called lance lacewings, stream lacewings or giant lacewings, are found all over the world except North and Central America. There are around 225 extant species.

Hemerobiidae is a family of Neuropteran insects commonly known as brown lacewings, comprising about 500 species in 28 genera. Most are yellow to dark brown, but some species are green. They are small; most have forewings 4–10 mm long. These insects differ from the somewhat similar Chrysopidae not only by the usual coloring but also by the wing venation: hemerobiids differ from chrysopids in having numerous long veins and forked costal cross veins. Some genera are widespread, but most are restricted to a single biogeographical realm. Some species have reduced wings to the degree that they are flightless. Imagines (adults) of subfamily Drepanepteryginae mimic dead leaves. Hemerobiid larvae are usually less hairy than chrysopid larvae.

The Neuropterida are a clade, sometimes placed at superorder level, of holometabolous insects with over 5,700 described species, containing the orders Neuroptera, Megaloptera, and Raphidioptera (snakeflies).

The Berothidae are a family of winged insects of the order Neuroptera. They are known commonly as the beaded lacewings. The family was first named by Anton Handlirsch in 1906. The family consists of 24 genera and 110 living species distributed discontinuously worldwide, mostly in tropical and subtropical regions. Numerous extinct species have also been described. Their ecology is poorly known, but in the species where larval stages have been documented, the larvae are predators of termites.

The Nevrorthidae are a small family of lacewings in the order Neuroptera. There are 19 extant species in four genera, with a geographically disjunct distribution: Nevrorthus, comprising 5 species with scattered distributions around the Mediterranean; Austroneurorthus, with two species known from southeastern Australia; Nipponeurorthus, comprising 11 species known from China and Japan; and Sinoneurorthus, known from a single species described from Yunnan Province, China. They are traditionally placed in the Osmyloidea, alongside Osmylidae and the spongillaflies (Sisyridae), but some research has considered them to be the sister group to the rest of Neuroptera. The larvae have unique straight jaws that are curved at the tips, and live as unspecialised predators in the sandy bottom sediments of clear, fast flowing mountain rivers and streams. They pupate underwater on the underside of stones. The adults are likely predators or feed on honeydew and other sugar-rich fluids.

Nymphidae, sometimes called split-footed lacewings, are a family of winged insects of the order Neuroptera. There are 35 extant species native to Australia and New Guinea.

Psychopsidae is a family of winged insects of the order Neuroptera. They are commonly called silky lacewings.

Sisyridae, commonly known as spongeflies or spongillaflies, are a family of winged insects in the order Neuroptera. There are approximately 60 living species described, and several extinct species identified from the fossil record.

The dustywings, Coniopterygidae, are a family of Pterygota of the net-winged insect order (Neuroptera). About 460 living species are known. These tiny insects can usually be determined to genus with a hand lens according to their wing venation, but to distinguish species, examination of the genitals by microscope is usually necessary.

Ithonidae, commonly called moth lacewings and giant lacewings, is a small family of winged insects of the insect order Neuroptera. The family contains a total of ten living genera, and over a dozen extinct genera described from fossils. The modern Ithonids have a notably disjunct distribution, while the extinct genera had a more global range. The family is considered one of the most primitive living neuropteran families. The family has been expanded twice, first to include the genus Rapisma, formerly placed in the monotypic family Rapismatidae, and then in 2010 to include the genera that had been placed into the family Polystoechotidae. Both Rapismatidae and Polystoechotidae have been shown to nest into Ithonidae sensu lato. The larvae of ithonids are grub-like, subterranean and likely phytophagous.

Necroraphidia is an extinct genus of snakefly in the family Mesoraphidiidae. The genus is solely known from Early Cretaceous, Albian age, fossil amber found in Spain. Currently the genus comprises a single species, Necroraphidia arcuata.

Amarantoraphidia is an extinct genus of snakefly in the family Mesoraphidiidae. The genus is solely known from Early Cretaceous, Albian age, fossil amber found in Spain. Currently the genus comprises only a single species Amarantoraphidia ventolina.

Cantabroraphidia is an extinct genus of snakefly in the family Mesoraphidiidae. The genus is solely known from fossil amber found in Cantabria, northern Spain, dating to the Albian age of the Early Cretaceous Period. Currently the genus comprises a single species Cantabroraphidia marcanoi.

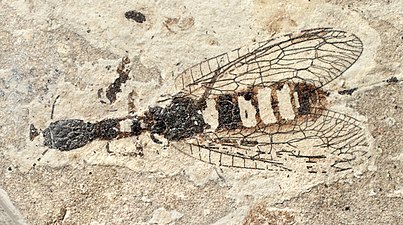

Mesoraphidiidae is an extinct family of snakeflies in the suborder Raphidiomorpha. The family lived from the Late Jurassic through the Late Cretaceous and is known from twenty-five genera. Mesoraphidiids have been found as both compression fossils and as inclusions in amber. The family was first proposed in 1925 by the Russian paleoentomologist Andrey Vasilyevich Martynov based on Upper Jurassic fossils recovered in Kazakhstan. The family was expanded in 2002 by the synonymizing of several other proposed snakefly families. The family was divided into three subfamilies and one tribe in a 2011 paper, further clarifying the relationships of the included genera.

Lebanoraphidia is an extinct genus of snakefly in the family Mesoraphidiidae. The genus is solely known from Cretaceous, Upper Neocomian, fossil amber found in Lebanon. Currently the genus is composed of a single species Lebanoraphidia nana.

Iberoraphidia is an extinct genus of snakefly in the family Mesoraphidiidae. The genus is solely known from a Cretaceous, Lower Barremian, fossil found in Spain. Currently the genus is composed of a single species, Iberoraphidia dividua.

This list of fossil arthropods described in 2011 is a list of new taxa of trilobites, fossil insects, crustaceans, arachnids and other fossil arthropods of every kind that have been described during the year 2011. The list only includes taxa at the level of genus or species.