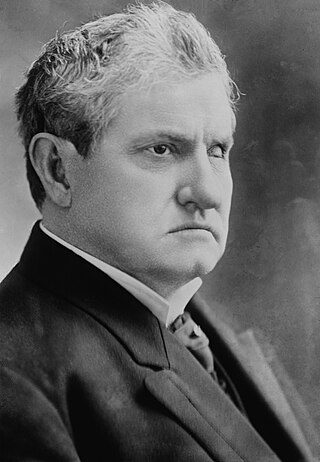

Benjamin Ryan Tillman was a politician of the Democratic Party who served as governor of South Carolina from 1890 to 1894, and as a United States Senator from 1895 until his death in 1918. A white supremacist who opposed civil rights for black Americans, Tillman led a paramilitary group of Red Shirts during South Carolina's violent 1876 election. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, he defended lynching, and frequently ridiculed black Americans in his speeches, boasting of having helped kill them during that campaign.

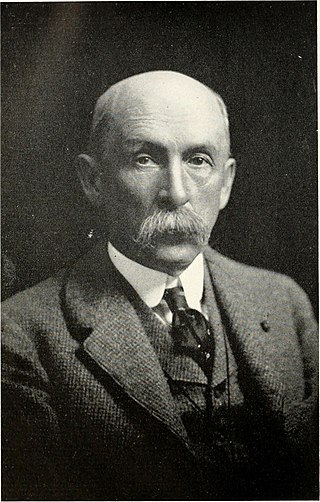

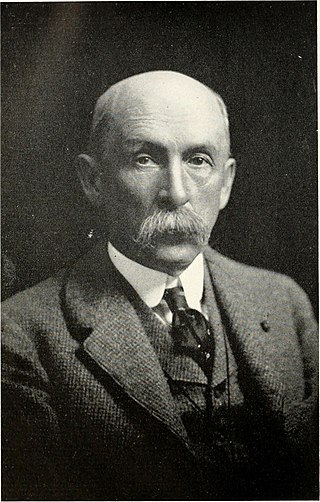

Wade Hampton III was the scion of one of the richest families in the ante-bellum South, owning thousands of acres of cotton land in South Carolina and Mississippi, as well as thousands of slaves. He became a senior general in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during the American Civil War. He also had a career as a leading Democratic politician in state and national affairs.

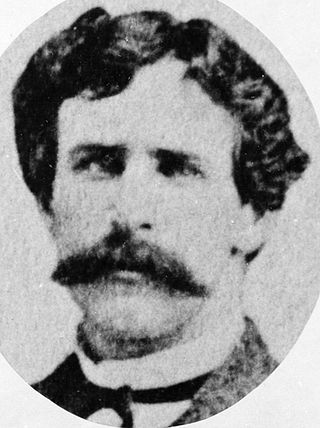

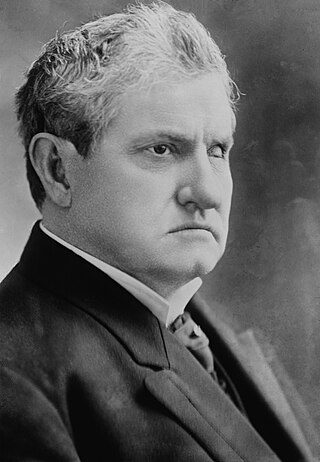

Daniel Lindsay Russell Jr. was an American politician who served as the 49th governor of North Carolina, from 1897 to 1901. An attorney and judge, he had also been elected as state representative and to the United States Congress, serving from 1879 to 1881. Although he fought with the Confederacy during the Civil War, Russell and his father were both Unionists. After the war, Russell joined the Republican Party in North Carolina, which was an unusual affiliation for one of the planter class. In the postwar period he served as a state judge, as well as in the state and national legislatures.

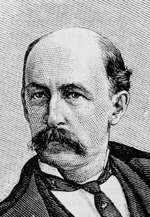

Daniel Henry Chamberlain was an American planter, lawyer, author and the 76th Governor of South Carolina from 1874 until 1876 or 1877. The federal government withdrew troops from the state and ended Reconstruction that year. Chamberlain was the last Republican governor of South Carolina until James B. Edwards was elected in 1974.

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the American Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce white supremacy. Their policy of Redemption was intended to oust the Radical Republicans, a coalition of freedmen, "carpetbaggers", and "scalawags". They were typically led by White yeomen and dominated Southern politics in most areas from the 1870s to 1910.

The Mississippi Plan of 1874–1875 was developed by white Southern Democrats as part of the white insurgency during the Reconstruction era in the Southern United States. It was devised by the Democratic Party in that state to overthrow the Republican Party in Mississippi by means of organized threats of violence and voter suppression against African American citizens and white Republican supporters. Democrats sought to regain political control of the state legislature and governor's office 'peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must.' Their justifications were articulated on a basis of discontent with governor Adelbert Ames' Republican administration, including spurious charges of corruption and high taxes. However, the violence that followed was centred on the desire to return white supremacy to the state. The success of the campaign led to similar plans being adopted by white Democrats in South Carolina and other majority-black states across the South.

Franklin Israel Moses Jr. was a South Carolina lawyer and editor who became active as a Republican politician in the state during the Reconstruction Era. He was elected to the legislature in 1868 and served as Speaker of the South Carolina House of Representatives. He was governor in 1872, serving into 1874. Enemies labelled him the 'Robber Governor'.

The Hamburg massacre was a riot in the United States town of Hamburg, South Carolina, in July 1876, leading up to the last election season of the Reconstruction era. It was the first of a series of civil disturbances planned and carried out by white Democrats in the majority-black Republican Edgefield District, with the goal of suppressing black Americans' civil rights and voting rights and disrupting Republican meetings, through actual and threatened violence.

The Independent Republican Party of South Carolina was a political party of South Carolina during Reconstruction. It was founded in 1872 to oppose the election of Franklin J. Moses Jr. for Governor of South Carolina after he had been nominated by the Republicans on August 21, 1872. Former governor James Lawrence Orr denounced the selection of Moses and led the formation of a new party.

The 1878 South Carolina gubernatorial election was held on November 5, 1878 to select the governor of South Carolina. Wade Hampton III was renominated by the Democrats and ran against no organized opposition in the general election to win reelection for a second two-year term.

The 1870 South Carolina gubernatorial election was held on October 19, 1870, to select the governor of the state of South Carolina. Governor Robert Kingston Scott easily won reelection based entirely on the strength of the black vote in the state. The election was significant because white conservatives of the state claimed it showed that political harmony between the white and black races was impossible and only through a straightout Democratic attempt would they be able to regain control of state government.

The Red Shirts or Redshirts of the Southern United States were white supremacist paramilitary terrorist groups that were active in the late 19th century in the last years of, and after the end of, the Reconstruction era of the United States. Red Shirt groups originated in Mississippi in 1875, when anti-Reconstruction private terror units adopted red shirts to make themselves more visible and threatening to Southern Republicans, both whites and freedmen. Similar groups in the Carolinas also adopted red shirts.

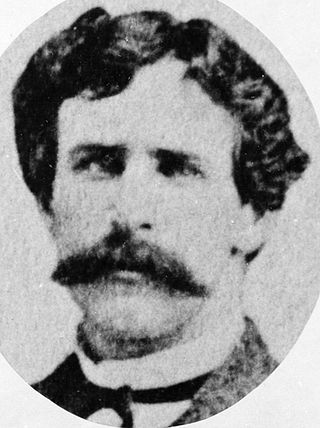

Martin Witherspoon Gary was a Confederate attorney, soldier, and politician from South Carolina. He attained the rank of brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He played a major leadership role in the 1876 Democratic political campaign to elect Wade Hampton III as governor, planning a detailed campaign to disrupt the Republican Party and black voters by violence and intimidation.

The South Carolina civil disturbances of 1876 were a series of race riots and civil unrest related to the Democratic Party's political campaign to take back control from Republicans of the state legislature and governor's office through their paramilitary Red Shirts division. Part of their plan was to disrupt Republican political activity and suppress black voting, particularly in counties where populations of whites and blacks were close to equal. Former Confederate general Martin W. Gary's "Plan of the Campaign of 1876" gives the details of planned actions to accomplish this.

The 1890 South Carolina gubernatorial election was held on Tuesday November 4, to elect the governor of South Carolina. Ben Tillman was nominated by the Democrats and easily won the general election against A.C. Haskell to become the 84th governor of South Carolina.

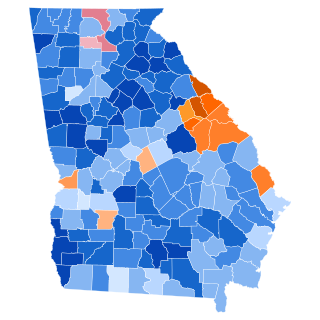

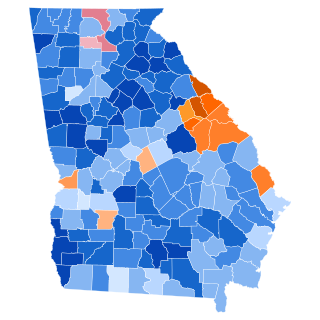

The 1948 United States presidential election in Georgia took place on November 2, 1948, as part of the wider United States presidential election. Voters chose 12 representatives, or electors, to the Electoral College, who voted for president and vice president.

The 1960 United States presidential election in South Carolina took place on November 8, 1960, as part of the 1960 United States presidential election. South Carolina voters chose eight representatives, or electors, to the Electoral College, who voted for president and vice president.

"Straight-Out Democratic Party" is the name used by three minor American political parties between 1872 and 1890.

The Ellenton riot or Ellenton massacre occurred in September 1876 and took place in South Carolina in the United States. The massacre was preceded by a series of civil disturbances earlier that year following tensions between the Democratic Party and the Republicans. Author Mark M. Smith concluded that there was one white and up to 100 blacks killed, with several white people wounded. While John S. Reynolds and Alfred B. Williams cite much lower numbers.

From December 1876 to April 1877, the Republican and Democratic parties in South Carolina each claimed to be the legitimate government. Both parties declared that the other had lost the election and that they controlled the governorship, the state legislature, and most state offices. Each government debated and passed laws, raised militias, collected taxes, and conducted other business as if the other did not exist. After four months of contested government, Daniel Henry Chamberlain, who claimed the governorship as a Republican, conceded to Democrat Wade Hampton III on April 11, 1877. This came after President Rutherford Hayes withdrew federal troops from the South.