The Circle line is a spiral-shaped London Underground line, running from Hammersmith in the west to Edgware Road and then looping around central London back to Edgware Road. The railway is below ground in the central section and on the loop east of Paddington. Unlike London's deep-level lines, the Circle line tunnels are just below the surface and are of similar size to those on British main lines. Printed in yellow on the Tube map, the 17-mile (27 km) line serves 36 stations, including most of London's main line termini. Almost all of the route, and all the stations, are shared with one or more of the three other sub-surface lines, namely the District, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan lines. On the Circle and Hammersmith & City lines combined, over 141 million passenger journeys were recorded in 2019.

Charing Cross is a London Underground station at Charing Cross in the City of Westminster. The station is served by the Bakerloo and Northern lines and provides an interchange with Charing Cross mainline station. On the Bakerloo line it is between Piccadilly Circus and Embankment stations, and on the Charing Cross branch of the Northern line it is between Leicester Square and Embankment stations. The station is in fare zone 1.

Aldwych is a closed station on the London Underground, located in the City of Westminster in Central London. It was opened in 1907 with the name Strand, after the street on which it is located. It was the terminus of the short Piccadilly line branch from Holborn that was a relic of the merger of two railway schemes. The station building is close to the Strand's junction with Surrey Street, near Aldwych. During its lifetime, the branch was the subject of a number of unrealised extension proposals that would have seen the tunnels through the station extended southwards, usually to Waterloo.

Highgate is a London Underground station and former railway station in Archway Road, in the London Borough of Haringey in north London. The station takes its name from nearby Highgate Village. It is on the High Barnet branch of the Northern line, between East Finchley and Archway stations, and is in Travelcard Zone 3.

The Metropolitan Railway was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex suburbs. Its first line connected the main-line railway termini at Paddington, Euston, and King's Cross to the City. The first section was built beneath the New Road using cut-and-cover between Paddington and King's Cross and in tunnel and cuttings beside Farringdon Road from King's Cross to near Smithfield, near the City. It opened to the public on 10 January 1863 with gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives, the world's first passenger-carrying designated underground railway.

The City and South London Railway (C&SLR) was the first successful deep-level underground "tube" railway in the world, and the first major railway to use electric traction. The railway was originally intended for cable-hauled trains, but owing to the bankruptcy of the cable contractor during construction, a system of electric traction using electric locomotives—an experimental technology at the time—was chosen instead.

The Metropolitan District Railway, also known as the District Railway, was a passenger railway that served London, England, from 1868 to 1933. Established in 1864 to complete an "inner circle" of lines connecting railway termini in London, the first part of the line opened using gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives. The Metropolitan Railway operated all services until the District Railway introduced its own trains in 1871. The railway was soon extended westwards through Earl's Court to Fulham, Richmond, Ealing and Hounslow. After completing the inner circle and reaching Whitechapel in 1884, it was extended to Upminster in Essex in 1902.

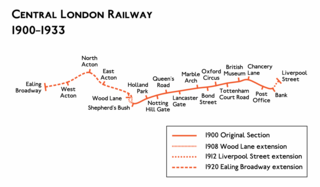

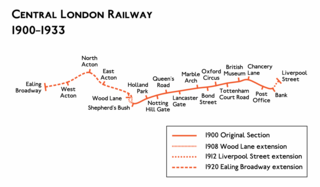

The Central London Railway (CLR), also known as the Twopenny Tube, was a deep-level, underground "tube" railway that opened in London in 1900. The CLR's tunnels and stations form the central section of the London Underground's Central line.

The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR), also known as the Hampstead Tube, was a railway company established in 1891 that constructed a deep-level underground "tube" railway in London. Construction of the CCE&HR was delayed for more than a decade while funding was sought. In 1900 it became a subsidiary of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), controlled by American financier Charles Yerkes. The UERL quickly raised the funds, mainly from foreign investors. Various routes were planned, but a number of these were rejected by Parliament. Plans for tunnels under Hampstead Heath were authorised, despite opposition by many local residents who believed they would damage the ecology of the Heath.

The County of London Plan was prepared for the London County Council in 1943 by John Henry Forshaw (1895–1973) and Sir Leslie Patrick Abercrombie (1879–1957).

The Sydney tramway network served the inner suburbs of Sydney, Australia, from 1879 until 1961. In its heyday, it was the largest in Australia, the second largest in the Commonwealth of Nations, and one of the largest in the world. The network was heavily worked, with about 1,600 cars in service at any one time at its peak during the 1930s . Patronage peaked in 1945 at 405 million passenger journeys. Its maximum street trackage totalled 291 km in 1923.

Nottingham and District Tramways Company Limited was a tramway operator from 1875 to 1897 based in Nottingham in the United Kingdom.

Edgware Road is a London Underground station on the Bakerloo line, located in the City of Westminster. It is between Paddington and Marylebone stations on the line and falls within Travelcard zone 1. The station is located on the north-east corner of the junction of Edgware Road, Harrow Road and Marylebone Road. It is adjacent to the Marylebone flyover.

The Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (GNP&BR), also known as the Piccadilly tube, was a railway company established in 1902 that constructed a deep-level underground "tube" railway in London, England. The GNP&BR was formed through a merger of two older companies, the Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway (B&PCR) and the Great Northern and Strand Railway (GN&SR). It also incorporated part of a tube route planned by a third company, the District Railway (DR). The combined company was a subsidiary of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL).

The Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (BS&WR), also known as the Bakerloo tube, was a railway company established in 1893 that built a deep-level underground "tube" railway in London. The company struggled to fund the work, and construction did not begin until 1898. In 1900, work was hit by the financial collapse of its parent company, the London & Globe Finance Corporation, through the fraud of Whitaker Wright, its main shareholder. In 1902, the BS&WR became a subsidiary of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) controlled by American financier Charles Yerkes. The UERL quickly raised the funds, mainly from foreign investors.

Edgware Road Tube schemes covers a number of proposals to build an underground railway in London, UK at the end of the 19th century. Each scheme envisaged building some form of rail tunnel along the Edgware Road in north-west London towards Victoria railway station.

The transport system now known as the London Underground began in 1863 with the Metropolitan Railway, the world's first underground railway. Over the next forty years, the early sub-surface lines reached out from the urban centre of the capital into the surrounding rural margins, leading to the development of new commuter suburbs. At the turn of the nineteenth century, new technology—including electric locomotives and improvements to the tunnelling shield—enabled new companies to construct a series of "tube" lines deeper underground. Initially rivals, the tube railway companies began to co-operate in advertising and through shared branding, eventually consolidating under the single ownership of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), with lines stretching across London.

Christchurch tramway routes have developed from lines that were first established by a troika of private tramway companies in the latter part of the 19th century, through to a significantly expanded system under the municipal Christchurch Tramway Board, to the City Council-built heritage circuit. These routes have been worked by all three main forms of tramway motive power and have significantly contributed to the development of Christchurch City in New Zealand's South Island.

Tramways in Exeter were operated between 1882 and 1931. The first horse-drawn trams were operated by the Exeter Tramway Company but in 1904 the Exeter Corporation took over. They closed the old network and replaced it with a new one powered by electricity.

The Royal Commission to Investigate the Various Projects for Establishing Railway Termini Within or in the Immediate Vicinity of the Metropolis was a royal commission established in 1846 with a remit to review and report on railway termini in London.