Pāramitā or pāramī is a Buddhist term often translated as "perfection". It is described in Buddhist commentaries as a noble character quality generally associated with enlightened beings. Pāramī and pāramitā are both terms in Pali but Pali literature makes greater reference to pāramī, while Mahayana texts generally use the Sanskrit pāramitā.

The Aṭṭhakavagga and the Pārāyanavagga are two small collections of suttas within the Pāli Canon of Theravada Buddhism. They are among the earliest existing Buddhist literature, and place considerable emphasis on the rejection of, or non-attachment to, all views.

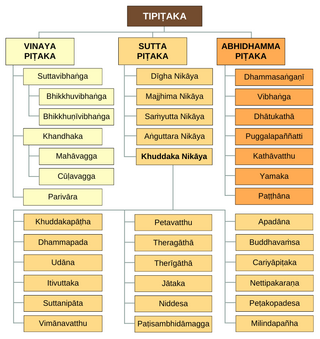

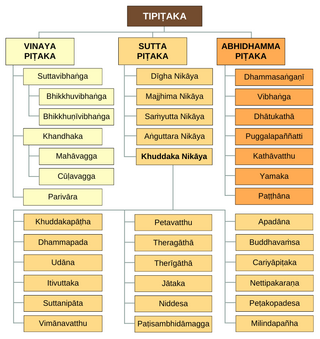

The Sutta Piṭaka is the second of the three division of the Pali Tripitaka, the definitive canonical collection of scripture of Theravada Buddhism. The other two parts of the Tripiṭaka are the Vinaya Piṭaka and the Abhidhamma Piṭaka. The Sutta Pitaka contains more than 10,000 suttas (teachings) attributed to the Buddha or his close companions.

Śrāvaka (Sanskrit) or Sāvaka (Pali) means "hearer" or, more generally, "disciple". This term is used in Buddhism and Jainism. In Jainism, a śrāvaka is any lay Jain so the term śrāvaka has been used for the Jain community itself. Śrāvakācāras are the lay conduct outlined within the treaties by Śvetāmbara or Digambara mendicants. "In parallel to the prescriptive texts, Jain religious teachers have written a number of stories to illustrate vows in practice and produced a rich répertoire of characters.".

In Buddhism, kammaṭṭhāna which literally means place of work. Its original meaning was someone's occupation but this meaning has developed into several distinct but related usages all having to do with Buddhist meditation.

The Dīgha Nikāya is a Buddhist scriptures collection, the first of the five Nikāyas, or collections, in the Sutta Piṭaka, which is one of the "three baskets" that compose the Pali Tipiṭaka of Theravada Buddhism. Some of the most commonly referenced suttas from the Digha Nikaya include the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta, which describes the final days and passing of the Buddha, the Sigālovāda Sutta in which the Buddha discusses ethics and practices for lay followers, and the Samaññaphala Sutta and Brahmajāla Sutta which describe and compare the point of view of the Buddha and other ascetics in India about the universe and time ; and the Poṭṭhapāda Sutta, which describes the benefits and practice of Samatha meditation.

The Khuddaka Nikāya is the last of the five Nikāyas, or collections, in the Sutta Pitaka, which is one of the "three baskets" that compose the Pali Tipitaka, the sacred scriptures of Theravada Buddhism. This nikaya consists of fifteen (Thailand), fifteen, or eighteen books (Burma) in different editions on various topics attributed to Gautama Buddha and his chief disciples.

The Theragāthā is a Buddhist text, a collection of short poems in Pali attributed to members of the early Buddhist sangha. It is classified as part of the Khuddaka Nikaya, the collection of minor books in the Sutta Pitaka. A similar text, the Therigatha, contains verses attributed to early Buddhist nuns.

The Apadāna is a collection of biographical stories found in the Khuddaka Nikaya of the Pāli Canon, the scriptures of Theravada Buddhism. G.P. Malalasekera describes it as 'a Buddhist Vitae Sanctorum' of Buddhist monks and nuns who lived during the lifetime of the Buddha.

Pali literature is concerned mainly with Theravada Buddhism, of which Pali is the traditional language. The earliest and most important Pali literature constitutes the Pāli Canon, the authoritative scriptures of Theravada school.

Aṭṭhakathā refers to Pali-language Theravadin Buddhist commentaries to the canonical Theravadin Tipitaka. These commentaries give the traditional interpretations of the scriptures. The major commentaries were based on earlier ones, now lost, in Prakrit and Sinhala, which were written down at the same time as the Canon, in the last century BCE. Some material in the commentaries is found in canonical texts of other schools of Buddhism, suggesting an early common source.

Utpalavarṇā was a Buddhist bhikkhuni, or nun, who was considered one of the top female disciples of the Buddha. She is considered the second of the Buddha's two chief female disciples, along with Khema. She was given the name Uppalavanna, meaning "color of a blue water lily", at birth due to the bluish color of her skin.

Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī or simply Prajāpatī was the foster-mother, step-mother and maternal aunt of the Buddha. In Buddhist tradition, she was the first woman to seek ordination for women, which she did from Gautama Buddha directly, and she became the first bhikṣuṇī.

The Mettā Sutta is the name used for two Buddhist discourses found in the Pali Canon. The one, more often chanted by Theravadin monks, is also referred to as Karaṇīyamettā Sutta after the opening word, Karaṇīyam, "(This is what) should be done." It is found in the Suttanipāta and Khuddakapāṭha. It is ten verses in length and it extols both the virtuous qualities and the meditative development of mettā (Pali), traditionally translated as "loving kindness" or "friendliness". Additionally, Thanissaro Bhikkhu's translation, "goodwill", underscores that the practice is used to develop wishes for unconditional goodwill towards the object of the wish.

The Nettipakaraṇa is a Buddhist scripture, sometimes included in the Khuddaka Nikaya of Theravada Buddhism's Pali Canon. The main theme of this text is Buddhist Hermeneutics through a systematization of the Buddha's teachings. It is regarded as canonical by the Burmese Theravada tradition, but isn't included in other Theravada canons.

In Buddhism, the bodhipakkhiyā dhammā are qualities conducive or related to awakening/understanding, i.e. the factors and wholesome qualities which are developed when the mind is trained.

Buddhist poetry is a genre of literature that forms a part of Buddhist discourse.

Thero is an honorific term in Pali for senior bhikkhus and bhikkhunis in the Buddhist monastic order. The word literally means "elder". These terms, appearing at the end of a monastic's given name, are used to distinguish those who have at least 10 years since their upasampada. The name of an important collection of very early Buddhist poetry is called the Therigatha, "verses of the therīs".

The Pāḷi Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

A bhikkhunī is a Buddhist nun, fully ordained female in Buddhist monasticism. Bhikkhunīs live by the Vinaya, a set of either 311 Theravada, 348 Dharmaguptaka, or 364 Mulasarvastivada school rules. Until recently, the lineages of female monastics only remained in Mahayana Buddhism and thus were prevalent in countries such as China, Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Vietnam, while a few women have taken the full monastic vows in the Theravada and Vajrayana schools. The official lineage of Tibetan Buddhist bhikkhunīs recommenced on 23 June 2022 in Bhutan when 144 nuns, most of them Bhutanese, were fully ordained.