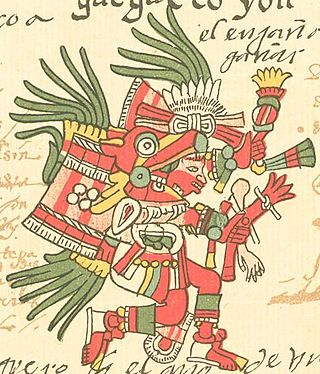

Tezcatlipoca or Tezcatl Ipoca was a central deity in Aztec religion. He is associated with a variety of concepts, including the night sky, hurricanes, obsidian, and conflict. He was considered one of the four sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, the primordial dual deity. His main festival was Toxcatl, which, like most religious festivals of Aztec culture, involved human sacrifice.

Tlāhuizcalpantēcuhtli is a principal member of the pantheon of gods within the Aztec religion, representing the Morning Star Venus. The name comes from the Nahuatl words tlāhuizcalpan "dawn" and tēcuhtli "lord". Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli is one of the thirteen Lords of the Day, representing the 12th day of the Aztec trecena.

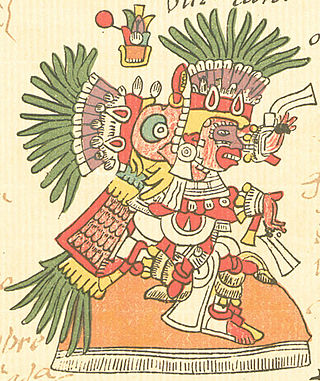

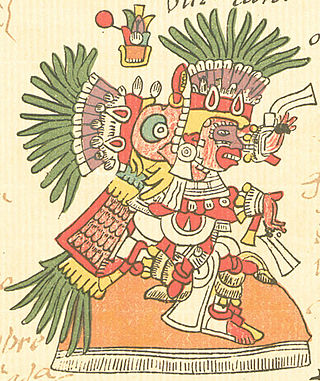

In Aztec mythology, Tonacatecuhtli was a creator and fertility god, worshipped for populating the earth and making it fruitful. Most Colonial-era manuscripts equate him with Ōmetēcuhtli. His consort was Tonacacihuatl.

Cipactli was the first day of the Aztec divinatory count of 13 X 20 days and Cipactonal "Sign of Cipactli" was considered to have been the first diviner. In Aztec cosmology, the crocodile symbolized the earth floating in the primeval waters. According to one Aztec tradition, Teocipactli "Divine Crocodile" was the name of a survivor of the flood who rescued himself in a canoe and again repopulated the earth. In the Mixtec Vienna Codex, Crocodile is a day associated with dynastic beginnings.

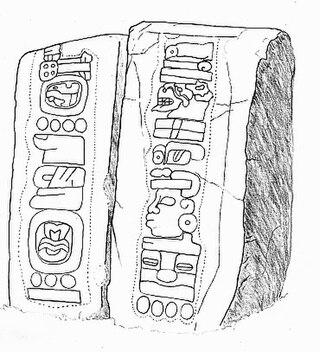

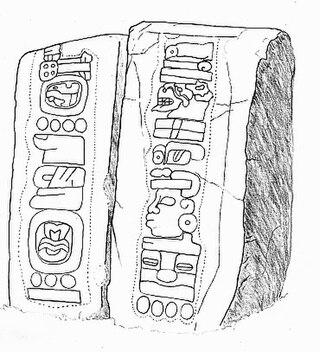

The Maya calendar is a system of calendars used in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and in many modern communities in the Guatemalan highlands, Veracruz, Oaxaca and Chiapas, Mexico.

The Aztec or Mexica calendar is the calendrical system used by the Aztecs as well as other Pre-Columbian peoples of central Mexico. It is one of the Mesoamerican calendars, sharing the basic structure of calendars from throughout the region.

The tzolkʼin is the 260-day Mesoamerican calendar used by the Maya civilization of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

The calendrical systems devised and used by the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica, primarily a 260-day year, were used in religious observances and social rituals, such as divination.

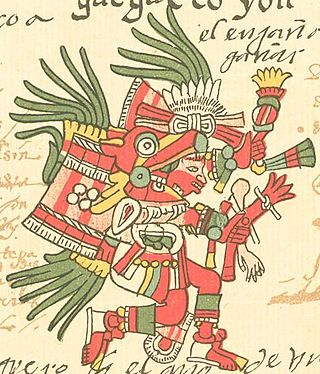

In Aztec mythology, Huēhuehcoyōtl is the auspicious Pre-Columbian god of music, dance, mischief, and song. He is the patron of uninhibited sexuality and rules over the day sign in the Aztec calendar named cuetzpallin (lizard) and the fourth trecena Xochitl.

A trecena is a 13-day period used in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican calendars. The 260-day calendar was divided into 20 trecenas. Trecena is derived from the Spanish chroniclers and translates to "a group of thirteen" in the same way that a dozen relates to the number twelve. It is associated with the Aztecs, but is called different names in the calendars of the Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, and others of the region.

A veintena is the Spanish-derived name for a 20-day period used in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican calendars. The division is often casually referred to as a "month", although it is not coordinated with the lunar cycle. The term is most frequently used with respect to the 365-day Aztec calendar, the xiuhpohualli, although 20-day periods are also used in the 365-day Maya calendar, as well as by other Mesoamerican civilizations such as the Zapotec and Mixtec.

Macuiltochtli is one of the five deities from Aztec and other central Mexican pre-Columbian mythological traditions who, known collectively as the Ahuiateteo, symbolized excess, over-indulgence and the attendant punishments and consequences thereof.

The Codex Magliabechiano is a pictorial Aztec codex created during the mid-16th century, in the early Spanish colonial period. It is representative of a set of codices known collectively as the Magliabechiano Group. The Codex Magliabechiano is based on an earlier unknown codex, which is assumed to have been the prototype for the Magliabechiano Group. It is named after Antonio Magliabechi, a 17th-century Italian manuscript collector, and is held in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, Italy.

The Codex Borbonicus is an Aztec codex written by Aztec priests shortly before or after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. It is named after the Palais Bourbon in France and kept at the Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée Nationale in Paris. The codex is an outstanding example of how Aztec manuscript painting is crucial for the understanding of Mexica calendric constructions, deities, and ritual actions.

The tonalamatl is a divinatory almanac used in central Mexico in the decades, and perhaps centuries, leading up to the Spanish conquest. The word itself is Nahuatl in origin, meaning "pages of days".

The Codex Borgia, also known as Codex Borgianus, Manuscrit de Veletri and Codex Yohualli Ehecatl, is a pre-Columbian Middle American pictorial manuscript from Central Mexico featuring calendrical and ritual content, dating from the 16th century. It is named after the 18th century Italian cardinal, Stefano Borgia, who owned it before it was acquired by the Vatican Library after the cardinal's death in 1804.

The xiuhpōhualli is a 365-day calendar used by the Aztecs and other pre-Columbian Nahua peoples in central Mexico. It is composed of eighteen 20-day "months," which through Spanish usage came to be known as veintenas, with an inauspicious, separate 5-day period at the end of the year called the nēmontēmi. The name given to the 20-day periods in pre-Columbian times is unknown, and though the Nahuatl word for moon or month, mētztli, is sometimes used today to describe them, the sixteenth-century missionary and ethnographer, Diego Durán explained that:

In ancient times the year was composed of eighteen months, and thus it was observed by these Indian people. Since their months were made of no more than twenty days, these were all the days contained in a month, because they were not guided by the moon but by the days; therefore, the year had eighteen months. The days of the year were counted twenty by twenty.

Toxcatl was the name of the fifth twenty-day month or "veintena" of the Aztec calendar which lasted approximately from the 5th to the 22nd May, and of the festival which was held every year in this month. The Festival of Toxcatl was dedicated to the god Tezcatlipoca and featured the sacrifice of a young man who had been impersonating the deity for a full year.

In the Aztec culture, a tecpatl was a flint or obsidian knife with a lanceolate figure and double-edged blade, with elongated ends. Both ends could be rounded or pointed, but other designs were made with a blade attached to a handle. It can be represented with the top half red, reminiscent of the color of blood, in representations of human sacrifice and the rest white, indicating the color of the flint blade.

The Aubin Tonalamatl is a Nahuatl screenfold manuscript painted on native paper. It was made sometime in the early 16th century, but after 1520. The word "tonalamatl" is made up of two Nahuatl words, "tonalli" meaning day, and "amatl" referring to the paper substrate that this codex is written on. While it originally consisted of 20 pages, only 18 remain today as 2 have gone missing. The physical document itself has had an interesting history as it was taken from the original owners in Mexico and since the retrieved from the French. Today, the Aubin Tonalamatl is entrusted in the hands of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). The content held within this codex has been significant to our understanding of Aztec culture and time keeping systems.