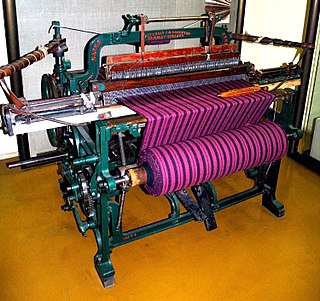

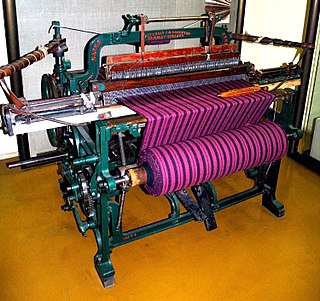

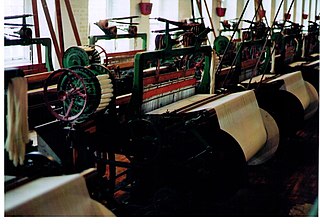

A loom is a device used to weave cloth and tapestry. The basic purpose of any loom is to hold the warp threads under tension to facilitate the interweaving of the weft threads. The precise shape of the loom and its mechanics may vary, but the basic function is the same.

Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft, woof, or filling. The method in which these threads are interwoven affects the characteristics of the cloth. Cloth is usually woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. A fabric band that meets this definition of cloth can also be made using other methods, including tablet weaving, back strap loom, or other techniques that can be done without looms.

The spinning jenny is a multi-spindle spinning frame, and was one of the key developments in the industrialisation of textile manufacturing during the early Industrial Revolution. It was invented in 1764–1765 by James Hargreaves in Stan hill, Oswaldtwistle, Lancashire in England.

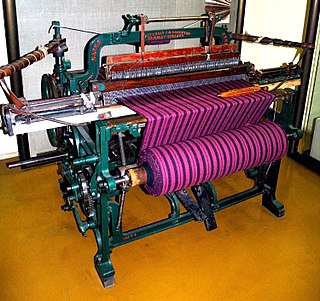

A power loom is a mechanized loom, and was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. The first power loom was designed and patented in 1785 by Edmund Cartwright. It was refined over the next 47 years until a design by the Howard and Bullough company made the operation completely automatic. This device was designed in 1834 by James Bullough and William Kenworthy, and was named the Lancashire loom.

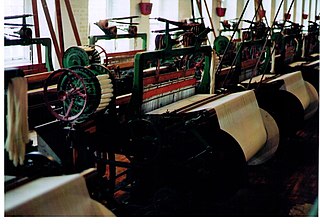

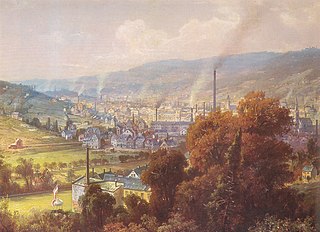

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

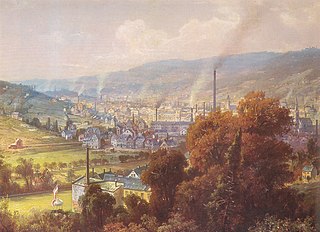

Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution was centred in south Lancashire and the towns on both sides of the Pennines in the United Kingdom. The main drivers of the Industrial Revolution were textile manufacturing, iron founding, steam power, oil drilling, the discovery of electricity and its many industrial applications, the telegraph and many others. Railroads, steamboats, the telegraph and other innovations massively increased worker productivity and raised standards of living by greatly reducing time spent during travel, transportation and communications.

The Lancashire Loom was a semi-automatic power loom invented by James Bullough and William Kenworthy in 1842. Although it is self-acting, it has to be stopped to recharge empty shuttles. It was the mainstay of the Lancashire cotton industry for a century.

Weaving and cloth trading communities of Western India particularly of Gujarat are called Vankar/Wankar/Vaniya. The four major woven fabrics produced by these communities are cotton, silk, khadi and linen. Today majority of these community members are not engaged in their ancestral weaving occupation still some population of these community contribute themselves in traditional handloom weaving of famous Patola of Patan, Kachchh shawl of Bhujodi in Kutch, Gharchola and Crotchet of Jamnagar, Zari of Surat, Mashroo of Patan and Mandvi in Kutch, Bandhani of Jamnagar, Anjar and Bhuj, Motif, Leheria, Dhamakda and Ajrak, Nagri sari, Tangaliya Shawl, Dhurrie, Kediyu, Heer Bharat, Abhala, Phento and art of Gudri. Vankar is described as a caste as well as a community.

Queen Street Mill is a former weaving mill in Harle Syke, a suburb to the north-east of Burnley, Lancashire, that is a Grade I listed building. It now operates as a museum and cafe. Currently open for public tours between April and November. Over winter the café is opened on Wednesdays. It is also viewable with private bookings.

Congleton, Macclesfield, Bollington and Stockport, England, were traditionally silk-weaving towns. Silk was woven in Cheshire from the late 1600s. The handloom weavers worked in the attic workshops in their own homes. Macclesfield was famous for silk buttons manufacture. The supply of silk from Italy was precarious and some hand throwing was done, giving way after 1732 to water-driven mills, which were established in Stockport and Macclesfield.

A weaving shed is a distinctive type of mill developed in the early 1800s in Lancashire, Derbyshire and Yorkshire to accommodate the new power looms weaving cotton, silk, woollen and worsted. A weaving shed can be a stand-alone mill, or a component of a combined mill. Power looms cause severe vibrations requiring them to be located on a solid ground floor. In the case of cotton, the weaving shed needs to remain moist. Maximum daylight is achieved, by the sawtooth "north-facing roof lights".

Bancroft Shed was a weaving shed in Barnoldswick, Lancashire, England, situated on the road to Skipton. Construction was started in 1914 and the shed was commissioned in 1920 for James Nutter & Sons Limited. The mill closed on 22 December 1978 and was demolished. The engine house, chimneys and boilers have been preserved and maintained as a working steam museum. The mill was the last steam-driven weaving shed to be constructed and the last to close.

The more looms system was a productivity strategy introduced in the Lancashire cotton industry, whereby each weaver would manage a greater number of looms. It was an alternative to investing in the more productive Northrop automatic looms in the 1930s. It caused resentment, resulted in industrial action, and failed to achieve any significant cost savings.

"Kissing the shuttle" is the term for a process by which weavers used their mouths to pull thread through the eye of a shuttle when the pirn was replaced. The same shuttles were used by many weavers, and the practice was unpopular. It was outlawed in the U.S. state of Massachusetts in 1911 but continued even after it had been outlawed in Lancashire, England in 1952. The Lancashire cotton industry was loath to invest in hand-threaded shuttles, or in the more productive Northrop automatic looms with self-threading shuttles, which were introduced in 1902.

Piece-rate lists were the ways of assessing a cotton operatives pay in Lancashire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They started as informal agreements made by one cotton master and their operatives then each cotton town developed their own list. Spinners merged all of these into two main lists which were used by all, while weavers used one 'unified' list.

Harle Syke mill is a weaving shed in Briercliffe on the outskirts of Burnley, Lancashire, England. It was built on a green field site in 1856, together with terraced houses for the workers. These formed the nucleus of the community of Harle Syke. The village expanded and six other mills were built, including Queen Street Mill.

William Horrocks, a cotton manufacturer of Stockport built an early power loom in 1803, based on the principles of Cartwright but including some significant improvements to cloth take up and in 1813 battening.

A Dandy loom was a hand loom, that automatically ratcheted the take-up beam. Each time the weaver moved the sley to beat-up the weft, a rachet and pawl mechanism advanced the cloth roller. In 1802 William Ratcliffe of Stockport patented a Dandy loom with a cast-iron frame. It was this type of Dandy loom that was used in the small dandy loom shops.

Handloom saris are a traditional textile art of Bangladesh and India. The production of handloom saris is important for economic development in rural India.

"Narrow cloth" is cloth of a comparatively narrow width, generally less than a human armspan; precise definitions vary.