In behavioral economics

In the context of behavioral economics, time inconsistency is related to how each different self of a decision-maker may have different preferences over current and future choices.

Consider, for example, the following question:

- (a) Which do you prefer, to be given 500 dollars today or 505 dollars tomorrow?

- (b) Which do you prefer, to be given 500 dollars 365 days from now or 505 dollars 366 days from now?

When this question is asked, to be time-consistent, one must make the same choice for (b) as for (a). According to George Loewenstein and Drazen Prelec, however, people are not always consistent. [1] People tend to choose "500 dollars today" and "505 dollars 366 days later", which is different from the time-consistent answer.

One common way in which selves may differ in their preferences is they may be modeled as all holding the view that "now" has especially high value compared to any future time. This is sometimes called the "immediacy effect" or "temporal discounting". As a result, the present self will care too much about itself and not enough about its future selves. The self control literature relies heavily on this type of time inconsistency, and it relates to a variety of topics including procrastination, addiction, efforts at weight loss, and saving for retirement.

Time inconsistency basically means that there is disagreement between a decision-maker's different selves about what actions should be taken. Formally, consider an economic model with different mathematical weightings placed on the utilities of each self. Consider the possibility that for any given self, the weightings that self places on all the utilities could differ from the weightings that another given self places on all the utilities. The important consideration now is the relative weighting between two particular utilities. Will this relative weighting be the same for one given self as it is for a different given self? If it is, then we have a case of time consistency. If the relative weightings of all pairs of utilities are all the same for all given selves, then the decision-maker has time-consistent preferences. If there exists a case of one relative weighting of utilities where one self has a different relative weighting of those utilities than another self has, then we have a case of time inconsistency and the decision-maker will be said to have time-inconsistent preferences.

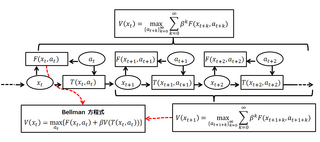

It is common in economic models that involve decision-making over time to assume that decision-makers are exponential discounters. Exponential discounting posits that the decision maker assigns future utility of any good according to the formula

where  is the present,

is the present,  is the utility assigned to the good if it were consumed immediately, and

is the utility assigned to the good if it were consumed immediately, and  is the "discount factor", which is the same for all goods and constant over time. Mathematically, it is the unique continuous function that satisfies the equation

is the "discount factor", which is the same for all goods and constant over time. Mathematically, it is the unique continuous function that satisfies the equation

that is, the ratio of utility values for a good at two different moments of time only depends on the interval between these times, but not on their choice. (If you're willing to pay 10% over list price to buy a new phone today instead of paying list price and having it delivered in a week, you'd also be willing to pay extra 10% to get it one week sooner if you were ordering it six months in advance.)

If  is the same for all goods, then it is also the case that

is the same for all goods, then it is also the case that

that is, if good A is assigned higher utility than good B at time  , that relationship also holds at all other times. (If you'd rather eat broccoli than cake tomorrow for lunch, you'll also pick broccoli over cake if you're hungry right now.)

, that relationship also holds at all other times. (If you'd rather eat broccoli than cake tomorrow for lunch, you'll also pick broccoli over cake if you're hungry right now.)

Exponential discounting yields time-consistent preferences. Exponential discounting and, more generally, time-consistent preferences are often assumed in rational choice theory, since they imply that all of a decision-maker's selves will agree with the choices made by each self. Any decision that the individual makes for himself in advance will remain valid (i.e., an optimal choice) as time advances, unless utilities themselves change.

However, empirical research makes a strong case that time inconsistency is, in fact, standard in human preferences. This would imply disagreement by people's different selves on decisions made and a rejection of the time consistency aspect of rational choice theory.

For example, consider having the choice between getting the day off work tomorrow or getting a day and a half off work one month from now. Suppose you would choose one day off tomorrow. Now suppose that you were asked to make that same choice ten years ago. That is, you were asked then whether you would prefer getting one day off in ten years or getting one and a half days off in ten years and one month. Suppose that then you would have taken the day and a half off. This would be a case of time inconsistency because your relative preferences for tomorrow versus one month from now would be different at two different points in time—namely now versus ten years ago. The decision made ten years ago indicates a preference for delayed gratification, but the decision made just before the fact indicates a preference for immediate pleasure.

More generally, humans have a systematic tendency to switch towards "vices" (products or activities which are pleasant in the short term) from "virtues" (products or activities which are seen as valuable in the long term) as the moment of consumption approaches, even if this involves changing decisions made in advance.

One way that time-inconsistent preferences have been formally introduced into economic models is by first giving the decision-maker standard exponentially discounted preferences, and then adding another term that heavily discounts any time that is not now. Preferences of this sort have been called "present-biased preferences". The hyperbolic discounting model is another commonly used model that allows one to obtain more realistic results with regard to human decision-making.

A different form of dynamic inconsistency arises as a consequence of "projection bias" (not to be confused with a defense mechanism of the same name). Humans have a tendency to mispredict their future marginal utilities by assuming that they will remain at present levels. This leads to inconsistency as marginal utilities (for example, tastes) change over time in a way that the individual did not expect. For example, when individuals are asked to choose between a piece of fruit and an unhealthy snack (such as a candy bar) for a future meal, the choice is strongly affected by their "current" level of hunger. Individuals may become addicted to smoking or drugs because they underestimate future marginal utilities of these habits (such as craving for cigarettes) once they become addicted. [2]