Paddington, also known as London Paddington, is a London railway station and London Underground station complex, located on Praed Street in the Paddington area. The site has been the London terminus of services provided by the Great Western Railway and its successors since 1838. Much of the main line station dates from 1854 and was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. As of the 2022–23 Office of Rail & Road Statistics, it is the second busiest station in the United Kingdom, after London Liverpool Street, with 59.2 million entries and exits.

The India Gate is a war memorial located near the Kartavya path on the eastern edge of the "ceremonial axis" of New Delhi, formerly called Rajpath in New Delhi. It stands as a memorial to 74,187 soldiers of the Indian Army who died between 1914 and 1921 in the First World War, in France, Flanders, Mesopotamia, Persia, East Africa, Gallipoli and elsewhere in the Near and the Far East, and the Third Anglo-Afghan War. 13,300 servicemen's names, including some soldiers and officers from the United Kingdom, are inscribed on the gate. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, the gate evokes the architectural style of the ancient Roman triumphal arches such as the Arch of Constantine in Rome, and later memorial arches; it is often compared to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and the Gateway of India in Mumbai.

The Royal Artillery Memorial is a First World War memorial located on Hyde Park Corner in London, England. Designed by Charles Sargeant Jagger, with architectural work by Lionel Pearson, and unveiled in 1925, the memorial commemorates the 49,076 soldiers from the Royal Artillery killed in the First World War. The static nature of the conflict, particularly on the Western Front, meant that artillery played a major role in the war, though physical reminders of the fighting were often avoided in the years after the war. The Royal Artillery War Commemoration Fund (RAWCF) was formed in 1918 to preside over the regiment's commemorations, aware of some dissatisfaction with memorials to previous wars. The RAWCF approached several eminent architects but its insistence on a visual representation of artillery meant that none was able to produce a satisfactory design. Thus they approached Jagger, himself an ex-soldier who had been wounded in the war. Jagger produced a design which was accepted in 1922, though he modified it several times before construction.

Charles Sargeant Jagger was a British sculptor who, following active service in the First World War, sculpted many works on the theme of war. He is best known for his war memorials, especially the Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner and the Great Western Railway War Memorial in Paddington Railway Station. He also designed several other monuments around Britain and other parts of the world.

The Cenotaph is a war memorial on Whitehall in London, England. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, it was unveiled in 1920 as the United Kingdom's national memorial to the dead of Britain and the British Empire of the First World War, was rededicated in 1946 to include those of the Second World War, and has since come to represent the Commonwealth casualties from those and subsequent conflicts. The word cenotaph is derived from Greek, meaning 'empty tomb'. Most of the dead were buried close to where they fell; thus, the Cenotaph symbolises their absence and is a focal point for public mourning. The original temporary Cenotaph was erected in 1919 for a parade celebrating the end of the First World War, at which more than 15,000 servicemen, including French and American soldiers, saluted the monument. More than a million people visited the site within a week of the parade.

Rochdale Cenotaph is a First World War memorial on the Esplanade in Rochdale, Greater Manchester, in the north west of England. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, it is one of seven memorials in England based on his Cenotaph in London and one of his more ambitious designs. The memorial was unveiled in 1922 and consists of a raised platform bearing Lutyens' characteristic Stone of Remembrance next to a 10-metre (33 ft) pylon topped by an effigy of a recumbent soldier. A set of painted stone flags surrounds the pylon.

The Midland Railway War Memorial is a First World War memorial in Derby in the East Midlands of England. It was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and unveiled in 1921. The memorial commemorates employees of the Midland Railway who died while serving in the armed forces during the First World War. The Midland was one of the largest railway companies in Britain in the early 20th century, and the largest employer in Derby, where it had its headquarters. Around a third of the company's workforce, some 23,000 men, left to fight, of whom 2,833 were killed.

Macclesfield Cenotaph is a World War I memorial in Park Green, Macclesfield, Cheshire, England. It was unveiled in 1921, and consists of a stone pillar and pedestal and three bronze statues. One statue is that of a mourning female, and the others comprise Britannia laying a wreath over a soldier who had died from gassing, an unusual subject for a war memorial at the time. The memorial is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II* listed building.

Inglis Barracks was a military installation in Mill Hill, London, NW7. It was also referred to as Mill Hill Barracks. The site has been redeveloped and now contains a variety of modern housing.

The London Troops War Memorial, located in front of the Royal Exchange in the City of London, commemorates the men of London who fought in World War I and World War II.

The North Eastern Railway War Memorial is a First World War memorial in York in northern England. It was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens to commemorate employees of the North Eastern Railway (NER) who left to fight in the First World War and were killed while serving. The NER board voted in early 1920 to allocate £20,000 for a memorial and commissioned Lutyens. The committee for the York City War Memorial followed suit and also appointed Lutyens, but both schemes became embroiled in controversy. Concerns were raised from within the community about the effect of the NER memorial on the city walls and its impact on the proposed scheme for the city's war memorial, given that the two memorials were planned to be 100 yards apart and the city's budget was a tenth of the NER's. The controversy was resolved after Lutyens modified his plans for the NER memorial to move it away from the walls and the city opted for a revised scheme on land just outside the walls; coincidentally the land was owned by the NER, whose board donated it to the city.

The London and North Western Railway War Memorial is a First World War memorial located outside Euston station in London, England. The memorial was designed by Reginald Wynn Owen, architect to the London and North Western Railway (LNWR), and commemorates employees of the LNWR who were killed in the First World War. Some 37,000 LNWR employees left to fight in the war—around a third of the company's workforce—of whom over 3,000 were killed. As well as personnel, much of the company's infrastructure was turned over to the war effort. Of the £12,500 cost of the memorial, £4,000 was contributed by the employees and the company paid the remainder.

The equestrian statue of Edward Horner stands inside St Andrew's Church in the village of Mells in Somerset, south-western England. It was designed by the architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, as a memorial to Edward Horner, who died of wounds in the First World War. The sculpture was executed by Sir Alfred Munnings.

The equestrian statue of Ferdinand Foch stands in Lower Grosvenor Gardens, London. The sculptor was Georges Malissard and the statue is a replica of another raised in Cassel, France. Foch, appointed Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces on the Western Front in the Spring of 1918, was widely seen as the architect of Germany's ultimate defeat and surrender in November 1918. Among many other honours, he was made an honorary Field marshal in the British Army, the only French military commander to receive such a distinction. Following Foch's death in March 1929, a campaign was launched to erect a statue in London in his memory. The Foch Memorial Committee chose Malissard as the sculptor, who produced a replica of his 1928 statue of Foch at Cassel. The statue was unveiled by the Prince of Wales on 5 June 1930. Designated a Grade II listed structure in 1958, the statue's status was raised to Grade II* in 2016.

The statue of Paddington Bear at London Paddington station is a bronze sculpture by Marcus Cornish. Erected in 2000, it marks the association between Michael Bond's fictional bear and the station from which his name derives.

The County Fermanagh War Memorial stands in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It was originally constructed to commemorate the men of the town killed during the First World War, particularly those serving with the local regiments, the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons and the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. It was later altered to also commemorate those killed in the Second World War.

The City of Portsmouth War Memorial, also referred to as the Guildhall Square War Memorial, is a First World War memorial in Guildhall Square in the centre of Portsmouth, Hampshire, on the south coast of England. Portsmouth was and remains a port and home to a major naval dockyard. The dockyard and the armed forces provided much of the employment in the area in the early 20th century. As such, the town suffered significant losses in the First World War. Planning for a war memorial began shortly after the end of the conflict and a committee was established for the purpose. It selected a site adjacent to a railway embankment close to the Town Hall and chose the architects James Gibson and Walter Gordon, with sculptural elements by Charles Sargeant Jagger, from an open competition.

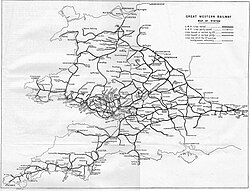

Railway war memorials are memorials dedicated to railway company employees killed in war. Some were commissioned by the railway companies while others were commissioned on behalf of the employees. Such memorials were first erected after the Second Boer War (1899–1902), though the vast majority appeared after the First World War. Over 400 railway war memorials are known to exist in Britain, ranging from paper rolls of honour to imposing stone monuments. Some have been destroyed or lost through multiple changes in ownership or redevelopment of their surroundings. The Railway Heritage Trust and Network Rail maintain a database of the known surviving memorials.

The Gladstone Memorial on the Strand, London is a bronze sculpture of the British statesman, created by Hamo Thornycroft between 1899-1905. The statue was erected as the national memorial to Gladstone and shows him in the robes of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The figure stands on a plinth surrounded by allegorical figures depicting four of the Virtues, Courage, Brotherhood, Education and Aspiration. The memorial is a Grade II listed structure.