Related Research Articles

Antisemitism is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against, Jews. This sentiment is a form of racism, and a person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Primarily, antisemitic tendencies may be motivated by negative sentiment towards Jews as a people or by negative sentiment towards Jews with regard to Judaism. In the former case, usually presented as racial antisemitism, a person's hostility is driven by the belief that Jews constitute a distinct race with inherent traits or characteristics that are repulsive or inferior to the preferred traits or characteristics within that person's society. In the latter case, known as religious antisemitism, a person's hostility is driven by their religion's perception of Jews and Judaism, typically encompassing doctrines of supersession that expect or demand Jews to turn away from Judaism and submit to the religion presenting itself as Judaism's successor faith—this is a common theme within the other Abrahamic religions. The development of racial and religious antisemitism has historically been encouraged by the concept of anti-Judaism, which is distinct from antisemitism itself.

Philosemitism, also called Judeophilia, is "defense, love, or admiration of Jews and Judaism". Such attitudes can be found in Western cultures across the centuries. The term originated in the nineteenth century by self-described German antisemites to describe their non-Jewish opponents. American-Jewish historian Daniel Cohen of the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies has asserted that philosemitism "can indeed easily recycle antisemitic themes, recreate Jewish otherness, or strategically compensate for Holocaust guilt."

Religious antisemitism is aversion to or discrimination against Jews as a whole based on religious doctrines of supersession, which expect or demand the disappearance of Judaism and the conversion of Jews to other faiths. This form of antisemitism has frequently served as the basis for false claims and religious antisemitic tropes against Judaism. Sometimes, it is called theological antisemitism.

"Who is a Jew?" is a basic question about Jewish identity and considerations of Jewish self-identification. The question pertains to ideas about Jewish personhood, which have cultural, ethnic, religious, political, genealogical, and personal dimensions. Orthodox Judaism and Conservative Judaism follow Jewish law (halakha), deeming people to be Jewish if their mothers are Jewish or if they underwent a halakhic conversion. Reform Judaism and Reconstructionist Judaism accept both matrilineal and patrilineal descent as well as conversion. Karaite Judaism predominantly follows patrilineal descent as well as conversion.

The history of the Jews in Denmark goes back to the 1600s. At present, the Jewish community of Denmark constitutes a small minority of about 6,000 persons within Danish society. The community's population peaked prior to the Holocaust at which time the Danish resistance movement took part in a collective effort to evacuate about 8,000 Jews and their families from Denmark by sea to nearby neutral Sweden, an act which ensured the safety of almost all the Danish Jews.

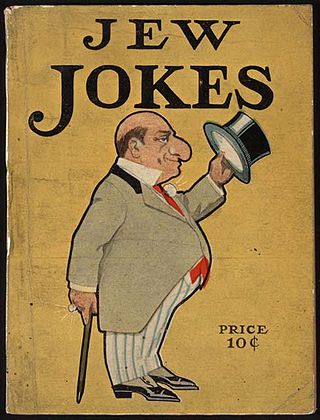

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews based on a belief or assertion that Jews constitute a distinct race that has inherent traits or characteristics that appear in some way abhorrent or inherently inferior or otherwise different from the traits or characteristics of the rest of a society. The abhorrence may find expression in the form of discrimination, stereotypes or caricatures. Racial antisemitism may present Jews, as a group, as a threat in some way to the values or safety of a society. Racial antisemitism can seem deeper-rooted than religious antisemitism, because for religious antisemites conversion of Jews remains an option and once converted the "Jew" is gone. In the context of racial antisemitism Jews cannot get rid of their Jewishness.

The history of the Jews in Belgium goes back to the 1st century CE until today. The Jewish community numbered 66,000 on the eve of the Second World War but after the war and The Holocaust, now is less than half that number.

Antisemitism has long existed in the United States. Most Jewish community relations agencies in the United States draw distinctions between antisemitism, which is measured in terms of attitudes and behaviors, and the security and status of American Jews, which are both measured by the occurrence of specific incidents.

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the modern State of Israel, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the region of Palestine—a region partly coinciding with the biblical Land of Israel—was flawed or unjust in some way.

Stereotypes of Jews are generalized representations of Jews, often caricatured and of a prejudiced and antisemitic nature.

Jews comprise approximately 10% of New York City's population, making the Jewish community the largest in the world outside of Israel. As of 2020, over 960,000 Jews lived in the five boroughs of New York City, and over 1.9 million Jews lived in the New York metropolitan area, approximately 25% of the American Jewish population.

African Americans and Jewish Americans have interacted throughout much of the history of the United States. This relationship has included widely publicized cooperation and conflict, and—since the 1970s—it has been an area of significant academic research. Cooperation during the Civil Rights Movement was strategic and significant, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Stereotypes of Jews in literature have evolved over the centuries. According to Louis Harap, nearly all European writers prior to the twentieth century projected the Jewish stereotypes in their works. Harap cites Gotthold Lessing's Nathan the Wise (1779) as the first time that Jews were portrayed in the arts as "human beings, with human possibilities and characteristics." Harap writes that, the persistence of the Jewish stereotype over the centuries suggests to some that "the treatment of the Jew in literature was completely static and was essentially unaffected by the changes in the Jewish situation in society as that society itself changed." He contrasts the opposing views presented in the two most comprehensive studies of the Jew in English literature, one by Montagu Frank Modder and the other by Edgar Rosenberg. Modder asserts that writers invariably "reflect the attitude of contemporary society in their presentation of the Jewish character, and that the portrayal changes with the economic and social changes of each decade." In opposition to Modder's "historical rationale", Rosenberg warns that such a perspective "is apt to slight the massive durability of a stereotype". Harap suggests that the recurrence of the Jewish stereotype in literature is itself one indicator of the continued presence of anti-Semitism among the readers of that literature.

Ashkenormativity refers to a form of Eurocentrism within Ashkenazi Jewish culture that confers privilege on Ashkenazi Jews relative to Jews of Sephardi, Mizrahi, Ethiopian, and other non-Ashkenazi backgrounds, as well as to the assumption that Ashkenazi culture is the default Jewish culture. The term is most commonly used in the United States, where the majority of Jews are Ashkenazi. Ashkenormativity is also alleged to exist in Israel, where Ashkenazi Jews experience cultural prominence despite no longer constituting a majority.

Jewface is a term that negatively characterizes stereotypical or inauthentic portrayals of Jewish people. The term has existed since the late 1800s, and most generally refers to performative Jewishness, regardless of the performer's identity.

Black Jews in New York City comprise one of the largest communities of Black Jews in the United States. Black Jews have lived in New York City since colonial times, with organized Black-Jewish and Black Hebrew Israelite communities emerging during the early 20th century. Black Jewish and Black Hebrew Israelite communities have historically been centered in Harlem, Brooklyn, The Bronx, and Queens. The Commandment Keepers movement originated in Harlem, while the Black Orthodox Jewish community is centered in Brooklyn. New York City is home to four historically Black synagogues with roots in the Black Hebrew Israelite community. A small Beta Israel (Ethiopian-Jewish) community also exists in New York City, many of whom emigrated from Israel. Black Hebrew Israelites are not considered Jewish by the New York Board of Rabbis, an organization representing mainstream Rabbinic Judaism. However, some Black Hebrew Israelite individuals in New York City are recognized as Jewish due to converting through the Orthodox, Conservative, or other Jewish movements.

Racism in Jewish communities is a source of concern for people of color, particularly for Jews of color. Black Jews, Indigenous Jews, and other Jews of color report that they experience racism from white Jews in many countries, including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Kenya, South Africa, and New Zealand. Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews also report experiences with racism by Ashkenazi Jews. The centering of Ashkenazi Jews is sometimes known as Ashkenormativity. In historically white-dominated countries with a legacy of anti-Black racism, such as the United States and South Africa, racism within the Jewish community often manifests itself as anti-Blackness. In Israel, racism among Israeli Jews often manifests itself as discrimination and prejudice against Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews, Ethiopian Jews, African immigrants, and Palestinians. Some critics describe Zionism as racist or settler colonial in nature.

The Scattered Nation is a philosemitic and racist speech by the U.S. Senator, Confederate officer, and slaveowner Zebulon Baird Vance, written sometime between 1868 and 1870. The speech praises the accomplishments of Jewish people, crediting Jews for much of what Vance considered great in Western civilization. Particular praise in reserved for white Jews of Central and Western European descent, while Black people and Jews of color are disparaged as culturally and racially inferior. Vance was a prominent defender of Jews during a time when antisemitism was common in the American South. While positively remembered for decades by the North Carolina Jewish community, Vance's reputation has declined in recent years due to his racism, support for slavery and the Confederacy, and promotion of Jewish stereotypes.

Jews of color is a neologism, primarily used in North America, that describes Jews from non-white racial and ethnic backgrounds, whether mixed-race, adopted, Jews by conversion, or part of national or geographic populations that are non-white. It is often used to identify Jews who are racially non-white, whose family origins are originally in African, Asian or Latin American countries, and to acknowledge a common experience for Jews who belong to racial, national, or geographic groups beyond white and Ashkenazi.

Zionist antisemitism or antisemitic Zionism refers to a phenomenon in which antisemites express support for Zionism and the State of Israel. In some cases, this support may be promoted for explicitly antisemitic reasons. Historically, this type of antisemitism has been most notable among Christian Zionists, who may perpetrate religious antisemitism while being outspoken in their support for Jewish sovereignty in Israel due to their interpretation of Christian eschatology. Similarly, people who identify with the political far-right, particularly in Europe and the United States, may support the Zionist movement because they seek to expel Jews from their country and see Zionism as the least complicated method of achieving this goal and satisfying their racial antisemitism.

References

- ↑ Stack, Liam (17 February 2020). ""Most Visible Jews" Fear Being Targets as Anti-Semitism Rises". The New York Times . Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "Bay Area Jews ask: Should our buildings be visibly Jewish?". J. The Jewish News of Northern California. 13 October 2021. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "Invisible Jews: Does internalized anti-Semitism play a role in unaddressed Jewish poverty in America?". Smith College . Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- 1 2 "How many Jews of color are there? Fewer than you think". The Forward. 18 May 2020. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "Anti-Jewish Hate Crimes Have Nothing to Do With Our Religion". Jewcy . Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "Revealing Jews: Culture and Visibility in Modern Central Europe" (PDF). Purdue University . Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ "Too Goyish". Canadian Jewish News. 19 December 2022. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ "Rabbi Streiffer: There is no such thing as looking Jewish". Canadian Jewish News. 10 January 2020. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ "Almost Half of Young U.S. Jews Feel No Connection to Religion, New Pew Survey Shows". Haaretz . Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "Our Response to Recent Incidents of Antisemitism in New York". UJA-Federation of New York . Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "HIDDEN CHILDREN: HARDSHIPS". Holocaust Encyclopedia . Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "Jewish visibility". The Jerusalem Post . Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "The Day: The cost of being visibly Jewish in Germany". Deutsche Welle . Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "The Jewish man who was the victim of a gang assault in New York says the level of hatred was troubling". CNN. 22 May 2021. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ "On visible and invisible Jews". Columbus Jewish News. Retrieved 2021-12-17.