A wide variety of languages are spoken throughout Asia, comprising different language families and some unrelated isolates. The major language families include Altaic, Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Caucasian, Dravidian, Indo-European, Afroasiatic, Siberian, Sino-Tibetan and Kra–Dai. Most, but not all, have a long history as a written language.

Sinhala, also known as Sinhalese, is an Indo-Aryan language primarily spoken by the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka, who make up the largest ethnic group on the island, numbering about 16 million. Sinhala is also spoken as the first language by other ethnic groups in Sri Lanka, totalling about 4 million people as of 2001. Sinhala is written using the Sinhala script, which is one of the Brahmic scripts, a descendant of the ancient Indian Brahmi script closely related to the Kadamba script.

In addition to its classical and literary form, Malay had various regional dialects established after the rise of the Srivijaya empire in Sumatra, Indonesia. Also, Malay spread through interethnic contact and trade across the Malay archipelago as far as the Philippines. That contact resulted in a lingua franca that was called Bazaar Malay or low Malay and in Malay Melayu Pasar. It is generally believed that Bazaar Malay was a pidgin, influenced by contact among Malay, Chinese, Portuguese, and Dutch traders.

Islam is a minority religion in Sri Lanka. 9.7% of the Sri Lankan population practice Islam. 1,967,227 persons adhere to Islam as per the census of 2012. Islam in Sri Lanka existed in communities along the Arab coastal trade routes in Ceylon as soon as the religion originated and had gained early acceptance in the Arabian Peninsula.

Sri Lanka Indo-Portuguese, Ceylonese Portuguese Creole or Sri Lankan Portuguese Creole (SLPC) is a language spoken in Sri Lanka. While the predominant languages of the island are Sinhala and Tamil, the interaction of the Portuguese and the Sri Lankans led to the evolution of a new language, Sri Lanka Portuguese Creole (SLPC), which flourished as a lingua franca on the island for over 350 years. SLPC continues to be spoken by an unknown, extremely small population. All speakers of SLPC are members of the Burgher community: descendants of the Portuguese and Dutch who founded families in Sri Lanka. Europeans, Eurasians and Burghers account for 0.2% of the Sri Lankan population. Though only a small group of people actually continue to speak SLPC, Portuguese cultural traditions are still in wide practice by many Sri Lankans who are neither of Portuguese descent nor Roman Catholics. SLPC is associated with the Sri Lanka Kaffir people, an ethnic minority group. SLPC has been considered the most important creole dialect in Asia because of its vitality and the influence of its vocabulary on the Sinhalese language. Lexical borrowing from Portuguese can be observed in many areas of the Sinhalese language. Portuguese influence has been so deeply absorbed into daily Sri Lankan life and behavior that these traditions will likely continue.

Sri Lankan English or Ceylonese English is the English language as it is used in Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka it is colloquially known as Singlish, a term dating from 1972. Sri Lankan English is principally categorised as the Standard Variety and the Non-standard Variety, which is called as "Not Pot English".The classification of SLE as a separate dialect of English is controversial. English in Sri Lanka is spoken by approximately 23.8% of the population, and widely used for official and commercial purposes. Sri Lankan English being the native language of approximately 5400 people thus challenges Braj Kachru's placement of it in the Outer Circle. Furthermore it is taught as a compulsory second language in local schools from grade one to thirteen and Sri Lankans pay special attention on learning English both as children and adults. It is considered even today that access and exposure to English from one's childhood in Sri Lanka is to be born with a silver spoon in one's mouth.

The Sri Lankan Kaffirs are an ethnic group in Sri Lanka who are partially descended from 16th-century Portuguese traders and Bantu slaves who were brought by them to work as labourers and soldiers to fight against the Sinhala Kings. They are very similar to the Zanj-descended populations in Iraq and Kuwait, and are known in Pakistan as Sheedis and in India as Siddis. The Kaffirs spoke a distinctive creole based on Portuguese, and the "Sri Lankan Kaffir language". Their cultural heritage includes the dance styles Kaffringna and Manja and their popular form of dance music Baila.

Hambantota District is a district in Southern Province, Sri Lanka. It is one of 25 districts of Sri Lanka, the second level administrative division of the country. The district is administered by a District Secretariat headed by a District Secretary appointed by the central government of Sri Lanka.

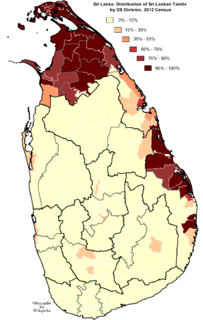

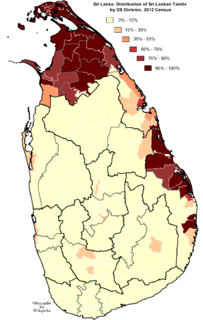

The Sri Lankan Tamil dialects or Ceylon Tamil dialects form a group of Tamil dialects used in the modern country of Sri Lanka by Sri Lankan Tamils and Moors that is distinct from the dialects of modern Tamil spoken in Tamil Nadu. Tamil dialects are differentiated by the phonological changes and sound shifts in their evolution from classical or Old Tamil. It is broadly categorized into four sub groups: Jaffna Tamil, Batticaloa Tamil, up country Indian origin Tamils and Negombo Tamil dialects. These dialects are also used by ethnic groups other than Tamils such as Sinhalese people, Sri Lankan Moors and Veddas, who consider them to be distinct.

Sri Lankan Moors are an ethnic minority group in Sri Lanka, comprising 9.2% of the country's total population. They are mainly native speakers of the Tamil language with influence of Arabic words. They are predominantly followers of Islam. The Sri Lankan Muslim community is divided as Sri Lankan Moors, Indian Moors and Sri Lankan Malays as per their history and traditions.

Negombo Tamil dialect or Negombo Fishermen’s Tamil is a Sri Lankan Tamil language dialect used by the fishers of Negombo, Sri Lanka. This is just one of the many dialects used by the remnant population of formerly Tamil speaking people of the western Puttalam District and Gampaha District of Sri Lanka. Those who still identify them as ethnic Tamils are known as Negombo Tamils or as Puttalam Tamils. Although most residents of these districts identify them as ethnic Sinhalese some are bilingual in both the languages.

Several languages are spoken in Sri Lanka within the Indo-Aryan, Dravidian and Austronesian families. Sri Lanka accords official status to Sinhala and Tamil. The languages spoken on the island nation are deeply influenced by the various languages in India, Europe and Southeast Asia. Arab settlers and the colonial powers of Portugal, the Netherlands and Britain have also influenced the development of modern languages in Sri Lanka. See below for the most-spoken languages of Sri Lanka.

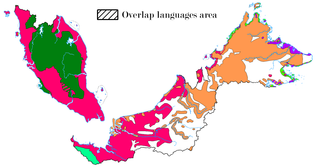

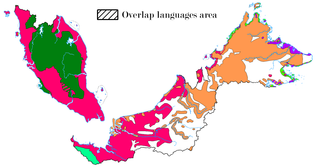

The indigenous languages of Malaysia belong to the Mon-Khmer and Malayo-Polynesian families. The national, or official, language is Malay which is the mother tongue of the majority Malay ethnic group. The main ethnic groups within Malaysia are the Malays, Chinese and Indians, with many other ethnic groups represented in smaller numbers, each with its own languages. The largest native languages spoken in East Malaysia are the Iban, Dusunic, and Kadazan languages. English is widely understood and spoken in service industries and is a compulsory subject in primary and secondary school. It is also the main language spoken in most private colleges and universities. English may take precedence over Malay in certain official contexts as provided for by the National Language Act, especially in the states of Sabah and Sarawak, where it may be the official working language.

Vedda is an endangered language which is used by the indigenous Vedda people of Sri Lanka. Additionally, communities such as Coast Veddas and Anuradhapura Veddas who do not strictly identify as Veddas also use words from the Vedda language in part for communication during hunting and/or for religious chants, throughout the island.

Sri Lankan Malays, also known in Sinhalese as Ja Minissu, are Sri Lankans with full or partial ancestry from the Indonesian/Malay Archipelago. The term is a misnomer as it is used as a historical catch-all term for all native ethnic groups of the Malay Archipelago who reside in Sri Lanka; the term does not apply solely to the ethnic Malays. They number approximately 40,000 and make up 0.2% of the Sri Lankan population, making them the fourth largest of the five main ethnic groups in the country.

Indians in Sri Lanka refer to Indians or people of Indian ancestry living in Sri Lanka, such as the Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka.

The Dutch Burghers are an ethnic group in Sri Lanka, of mixed Dutch, Portuguese Burghers and Sri Lankan descent. However, they are a different community when compared with Portuguese Burghers. Originally an entirely Protestant community, many Burghers today remain Christian but belong to a variety of denominations. The Dutch Burghers of Sri Lanka speak English and the local languages Sinhala and Tamil.

Alamat Lankapuri was a Malay language fortnightly publication in Jawi script, issued from Colombo, Ceylon. Alamat Lankapuri was first published in June 1869. It was the first Jawi script Malay-language newspaper printed worldwide. The newspaper was printed by lithograph.