The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), known informally as the Biodiversity Convention, is a multilateral treaty. The Convention has three main goals: the conservation of biological diversity ; the sustainable use of its components; and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from genetic resources. Its objective is to develop national strategies for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, and it is often seen as the key document regarding sustainable development.

A genetically modified organism (GMO) is any organism whose genetic material has been altered using genetic engineering techniques. The exact definition of a genetically modified organism and what constitutes genetic engineering varies, with the most common being an organism altered in a way that "does not occur naturally by mating and/or natural recombination". A wide variety of organisms have been genetically modified (GM), including animals, plants, and microorganisms.

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including the transfer of genes within and across species boundaries to produce improved or novel organisms. New DNA is obtained by either isolating and copying the genetic material of interest using recombinant DNA methods or by artificially synthesising the DNA. A construct is usually created and used to insert this DNA into the host organism. The first recombinant DNA molecule was made by Paul Berg in 1972 by combining DNA from the monkey virus SV40 with the lambda virus. As well as inserting genes, the process can be used to remove, or "knock out", genes. The new DNA can be inserted randomly, or targeted to a specific part of the genome.

Biosafety is the prevention of large-scale loss of biological integrity, focusing both on ecology and human health. These prevention mechanisms include the conduction of regular reviews of biosafety in laboratory settings, as well as strict guidelines to follow. Biosafety is used to protect from harmful incidents. Many laboratories handling biohazards employ an ongoing risk management assessment and enforcement process for biosafety. Failures to follow such protocols can lead to increased risk of exposure to biohazards or pathogens. Human error and poor technique contribute to unnecessary exposure and compromise the best safeguards set into place for protection.

Biosecurity refers to measures aimed at preventing the introduction and/or spread of harmful organisms intentionally or unintentionally outside their native range and/or within new environments. In agriculture, these measures are aimed at protecting food crops and livestock from pests, invasive species, and other organisms not conducive to the welfare of the human population. The term includes biological threats to people, including those from pandemic diseases and bioterrorism. The definition has sometimes been broadened to embrace other concepts, and it is used for different purposes in different contexts.

The precautionary principle is a broad epistemological, philosophical and legal approach to innovations with potential for causing harm when extensive scientific knowledge on the matter is lacking. It emphasizes caution, pausing and review before leaping into new innovations that may prove disastrous. Critics argue that it is vague, self-cancelling, unscientific and an obstacle to progress.

This is an index of conservation topics. It is an alphabetical index of articles relating to conservation biology and conservation of the natural environment.

Genetic use restriction technology (GURT), also known as terminator technology or suicide seeds, is the name given to proposed methods for restricting the use of genetically modified crops by activating some genes only in response to certain stimuli, especially to cause second generation seeds to be infertile. The development and application of GURTs is primarily an attempt by private sector agricultural breeders to increase the extent of protection on their innovations. The technology was originally developed under a cooperative research and development agreement between the Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture and Delta & Pine Land Company in the 1990s and is not yet commercially available.

The Biosafety Clearing-House is an international mechanism that exchanges information about the movement of genetically modified organisms, established under the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety. It assists Parties to implement the protocol’s provisions and to facilitate sharing of information on, and experience with, living modified organisms. It further assists Parties and other stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding the importation or release of GMOs.

Since the advent of genetic engineering in the 1970s, concerns have been raised about the dangers of the technology. Laws, regulations, and treaties were created in the years following to contain genetically modified organisms and prevent their escape. Nevertheless, there are several examples of failure to keep GM crops separate from conventional ones.

The traceability of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) describes a system that ensures the forwarding of the identity of a GMO from its production to its final buyer. Traceability is an essential prerequisite for the co-existence of GM and non-GM foods, and for the freedom of choice for consumers.

The Wingspread Conference on the Precautionary Principle was a three-day academic conference where the precautionary principle was defined. The January 1998 meeting took place at Wingspread, headquarters of the Johnson Foundation in Racine, Wisconsin, and involved 35 scientists, lawyers, policy makers and environmentalists from the United States, Canada and Europe.

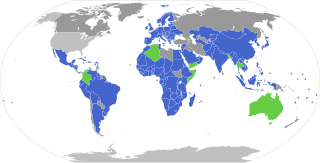

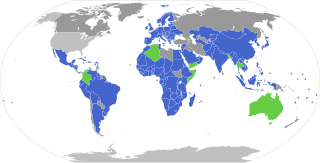

The regulation of genetic engineering varies widely by country. Countries such as the United States, Canada, Lebanon and Egypt use substantial equivalence as the starting point when assessing safety, while many countries such as those in the European Union, Brazil and China authorize GMO cultivation on a case-by-case basis. Many countries allow the import of GM food with authorization, but either do not allow its cultivation or have provisions for cultivation, but no GM products are yet produced. Most countries that do not allow for GMO cultivation do permit research. Most (85%) of the world's GMO crops are grown in the Americas. One of the key issues concerning regulators is whether GM products should be labeled. Labeling of GMO products in the marketplace is required in 64 countries. Labeling can be mandatory up to a threshold GM content level or voluntary. A study investigating voluntary labeling in South Africa found that 31% of products labeled as GMO-free had a GM content above 1.0%. In Canada and the USA labeling of GM food is voluntary, while in Europe all food or feed which contains greater than 0.9% of approved GMOs must be labelled.

The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity, also known as the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) is a 2010 supplementary agreement to the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Its aim is the implementation of one of the three objectives of the CBD: the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources, thereby contributing to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. It sets out obligations for its contracting parties to take measures in relation to access to genetic resources, benefit-sharing and compliance.

This is a list of notable events relating to the environment in 2003. They relate to environmental law, conservation, environmentalism and environmental issues.

The Biotechnology Regulatory Authority of India (BRAI) is a proposed regulatory body in India for uses of biotechnology products including genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The institute was first suggested under the Biotechnology Regulatory Authority of India (BRAI) draft bill prepared by the Department of Biotechnology in 2008. Since then, it has undergone several revisions.

A genetically modified tree is a tree whose DNA has been modified using genetic engineering techniques. In most cases the aim is to introduce a novel trait to the plant which does not occur naturally within the species. Examples include resistance to certain pests, diseases, environmental conditions, and herbicide tolerance, or the alteration of lignin levels in order to reduce pulping costs.

India and China are the two largest producers of genetically modified products in Asia. India currently only grows GM cotton, while China produces GM varieties of cotton, poplar, petunia, tomato, papaya and sweet pepper. Cost of enforcement of regulations in India are generally higher, possibly due to the greater influence farmers and small seed firms have on policy makers, while the enforcement of regulations was more effective in China. Other Asian countries that grew GM crops in 2011 were Pakistan, the Philippines and Myanmar. GM crops were approved for commercialisation in Bangladesh in 2013 and in Vietnam and Indonesia in 2014.

The hazards of synthetic biology include biosafety hazards to workers and the public, biosecurity hazards stemming from deliberate engineering of organisms to cause harm, and hazards to the environment. The biosafety hazards are similar to those for existing fields of biotechnology, mainly exposure to pathogens and toxic chemicals; however, novel synthetic organisms may have novel risks. For biosecurity, there is concern that synthetic or redesigned organisms could theoretically be used for bioterrorism. Potential biosecurity risks include recreating known pathogens from scratch, engineering existing pathogens to be more dangerous, and engineering microbes to produce harmful biochemicals. Lastly, environmental hazards include adverse effects on biodiversity and ecosystem services, including potential changes to land use resulting from agricultural use of synthetic organisms.