Internet censorship in Tunisia decreased in January 2011 following the ousting of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The successor acting government removed filters on social networking sites such as YouTube.

Internet censorship in Australia is enforced by both the country's criminal law as well as voluntarily enacted by internet service providers. The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) has the power to enforce content restrictions on Internet content hosted within Australia, and maintain a blocklist of overseas websites which is then provided for use in filtering software. The restrictions focus primarily on child pornography, sexual violence, and other illegal activities, compiled as a result of a consumer complaints process.

Censorship in South Asia can apply to books, movies, the Internet and other media. Censorship occurs on religious, moral and political grounds, which is controversial in itself as the latter especially is seen as contrary to the tenets of democracy, in terms of freedom of speech and the right to freely criticise the government.

The OpenNet Initiative (ONI) was a joint project whose goal was to monitor and report on internet filtering and surveillance practices by nations. Started in 2002, the project employed a number of technical means, as well as an international network of investigators, to determine the extent and nature of government-run internet filtering programs. Participating academic institutions included the Citizen Lab at the Munk Centre for International Studies, University of Toronto; Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard Law School; the Oxford Internet Institute (OII) at University of Oxford; and, The SecDev Group, which took over from the Advanced Network Research Group at the Cambridge Security Programme, University of Cambridge.

Use of the Internet in Yemen began in 1996 through the ISPs TeleYemen and the Public Telecommunications Corporation. The country has 8,243,772 internet users, 15,000,000 mobile cellular telephone subscriptions, more than 1,160 .ye domains, and around 3,631,200 Facebook users. By July 2016, 6,732,928 people were Internet users.

Internet censorship is the legal control or suppression of what can be accessed, published, or viewed on the Internet. Censorship is most often applied to specific internet domains but exceptionally may extend to all Internet resources located outside the jurisdiction of the censoring state. Internet censorship may also put restrictions on what information can be made internet accessible. Organizations providing internet access – such as schools and libraries – may choose to preclude access to material that they consider undesirable, offensive, age-inappropriate or even illegal, and regard this as ethical behavior rather than censorship. Individuals and organizations may engage in self-censorship of material they publish, for moral, religious, or business reasons, to conform to societal norms, political views, due to intimidation, or out of fear of legal or other consequences.

Internet censorship in Morocco was listed as selective in the social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas and as no evidence in the political area by the OpenNet Initiative (ONI) in August 2009. Freedom House listed Morocco's "Internet Freedom Status" as "Partly Free" in its 2018 Freedom on the Net report.

Sweden's internet usage in 2022 was 96%, higher than the European Union (EU) average of 89%. This contributes to Sweden's digital skills development, with 67% of Swedes possessing basic digital skills, compared to the EU's 54%. Additionally, 36% of Swedes have above-basic digital skills and 77% have basic digital content creation skills, exceeding the EU averages of 26% and 66%, respectively. Codeweek 2022 in Sweden also demonstrated gender inclusivity, with a female participation rate of 51%.

Censorship in Denmark has been prohibited since 1849 by the Constitution:

§ 77: Any person shall be at liberty to publish his ideas in print, in writing, and in speech, subject to his being held responsible in a court of law. Censorship and other preventive measures shall never again be introduced.

Use of the Internet in Qatar has grown rapidly and is now widespread, but Internet access is also heavily filtered.

In Ethiopia, the Internet penetration rate is 25% as of January 2022, and it is currently attempting a broad expansion of access throughout the country. These efforts have been hampered by the largely rural makeup of the Ethiopian population and the government's refusal to permit any privatization of the telecommunications market. Only 360,000 people had Internet access in 2008, a penetration rate of 0.4%. The state-owned Ethio Telecom is the sole Internet service provider (ISP) in the country. Ethio Telecom comes in at very high prices which makes it difficult for private users to purchase it.

The Internet in Kazakhstan is growing rapidly. Between 2001 and 2005, the number of Internet users increased from 200,000 to 1 million. By 2007, Kazakhstan reported Internet penetration levels of 8.5 percent, rising to 12.4 percent in 2008 and 34.3% in 2010. By 2013, Kazakhstani officials reported Internet penetration levels of 62.2 percent, with about 10 million users. There are five first-tier ISPs with international Internet connections and approximately 100 second-tier ISPs that are purchasing Internet traffic from the first-tier ISPs. As of 2019, more than 75% of Kazakhstan's population have access to the internet, a figure well ahead of any other country in Central Asia. The Internet consumption in the country rose from 356 PB in 2018 to 1,000 PB in 2022.

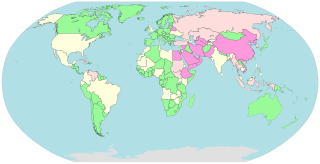

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance by country provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries around the world.

There is medium internet censorship in France, including limited filtering of child pornography, laws against websites that promote terrorism or racial hatred, and attempts to protect copyright. The "Freedom on the Net" report by Freedom House has consistently listed France as a country with Internet freedom. Its global ranking was 6 in 2013 and 12 in 2017. A sharp decline in its score, second only to Libya was noted in 2015 and attributed to "problematic policies adopted in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack, such as restrictions on content that could be seen as 'apology for terrorism,' prosecutions of users, and significantly increased surveillance."

The State Security Service is the national intelligence agency of the government of Uzbekistan. It was formerly known as the National Security Service.

In Russia, internet censorship is enforced on the basis of several laws and through several mechanisms. Since 2012, Russia maintains a centralized internet blacklist maintained by the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor).

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Europe provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Europe.

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Asia provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Asia

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in the Americas provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in the Americas.

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Africa provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Africa.