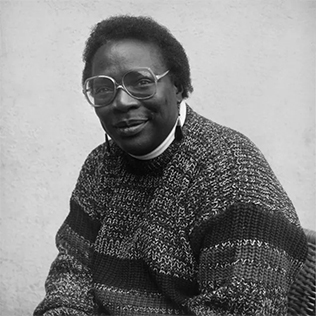

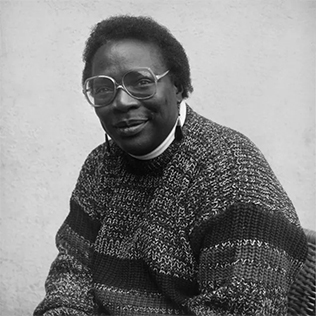

Audre Lorde was an American writer, professor, philosopher, intersectional feminist, poet and civil rights activist. She was a self-described "Black, lesbian, feminist, socialist, mother, warrior, poet" who dedicated her life and talents to confronting different forms of injustice, as she believed there could be "no hierarchy of oppressions" among "those who share the goals of liberation and a workable future for our children."

Lesbian feminism is a cultural movement and critical perspective that encourages women to focus their efforts, attentions, relationships, and activities towards their fellow women rather than men, and often advocates lesbianism as the logical result of feminism. Lesbian feminism was most influential in the 1970s and early 1980s, primarily in North America and Western Europe, but began in the late 1960s and arose out of dissatisfaction with the New Left, the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, sexism within the gay liberation movement, and homophobia within popular women's movements at the time. Many of the supporters of Lesbianism were actually women involved in gay liberation who were tired of the sexism and centering of gay men within the community and lesbian women in the mainstream women's movement who were tired of the homophobia involved in it.

Cherríe Moraga is a Xicana feminist, writer, activist, poet, essayist, and playwright. She is part of the faculty at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the Department of English since 2017, and in 2022 became a distinguished professor. Moraga is also a founding member of the social justice activist group La Red Xicana Indígena, which is network fighting for education, culture rights, and Indigenous Rights. In 2017, she co-founded, with Celia Herrera Rodríguez, Las Maestras Center for Xicana Indigenous Thought, Art, and Social Practice, located on the campus of UC Santa Barbara.

Black feminism is a branch of feminism that focuses on the African-American woman's experiences and recognizes the intersectionality of racism and sexism. Black feminism philosophy centers on the idea that "Black women are inherently valuable, that liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else's but because of our need as human persons for autonomy."

Barbara Smith is an American lesbian feminist and socialist who has played a significant role in Black feminism in the United States. Since the early 1970s, she has been active as a scholar, activist, critic, lecturer, author, and publisher of Black feminist thought. She has also taught at numerous colleges and universities for 25 years. Smith's essays, reviews, articles, short stories and literary criticism have appeared in a range of publications, including The New York Times Book Review, The Black Scholar, Ms., Gay Community News, The Guardian, The Village Voice, Conditions and The Nation. She has a twin sister, Beverly Smith, who is also a lesbian feminist activist and writer.

Chicana feminism is a sociopolitical movement, theory, and praxis that scrutinizes the historical, cultural, spiritual, educational, and economic intersections impacting Chicanas and the Chicana/o community in the United States. Chicana feminism empowers women to challenge institutionalized social norms and regards anyone a feminist who fights for the end of women's oppression in the community.

Founded in Upstate New York in 1978 by Maureen Brady and Judith McDaniel, Spinsters Ink is one of the oldest lesbian feminist publishers in the world. It is currently owned by publisher Linda Hill, who purchased the Spinsters Ink in 2005. Hill also owns Bella Books and Beanpole Books.

Azalea: A Magazine by Third World Lesbians was a quarterly periodical for Black, Asian, Latina, and Native American lesbians published between 1977 and 1983 by the Salsa Soul Sisters, Third World Wimmin Inc Collective. The Collective also published the Salsa Soul Sisters/Third World Women's Gay-zette.

Conditions was a lesbian feminist literary magazine that came out biannually from 1976 to 1980 and annually from 1980 until 1990, and included poetry, prose, essays, book reviews, and interviews. It was founded in Brooklyn, New York, by Elly Bulkin, Jan Clausen, Irena Klepfisz and Rima Shore.

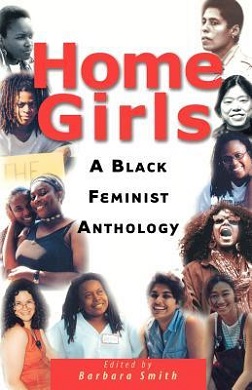

Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (1983) is a collection of Black lesbian and Black feminist essays, edited by Barbara Smith. The anthology includes different accounts from 32 black women of feminist ideology who come from a variety of different areas, cultures, and classes. This collection of writings is intended to showcase the similarities among black women from different walks of life. In the introduction, Smith states her belief that "Black feminism is, on every level, organic to Black experience." Writings within Home Girls support this belief through essays that exemplify black women's struggles and lived experiences within their race, gender, sexual orientation, culture, and home life. Topics and stories discussed in the writings often touch on subjects that in the past have been deemed taboo, provocative, and profound.

The Combahee River Collective (CRC) was a Black feminist lesbian socialist organization active in Boston, Massachusetts, from 1974 to 1980. The Collective argued that both the white feminist movement and the Civil Rights Movement were not addressing their particular needs as Black women and more specifically as Black lesbians. Racism was present in the mainstream feminist movement, while Delaney and Manditch-Prottas argue that much of the Civil Rights Movement had a sexist and homophobic reputation.

Beverly Smith in Cleveland, Ohio, is a Black feminist health advocate, writer, academic, theorist and activist who is also the twin sister of writer, publisher, activist and academic Barbara Smith. Beverly Smith is an instructor of Women's Health at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

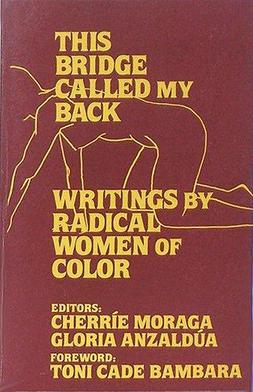

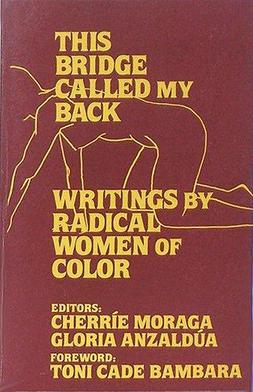

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color is a feminist anthology edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa, first published in 1981 by Persephone Press. The second edition was published in 1983 by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. The book's third edition was published by Third Woman Press until 2008, when it went out of print. In 2015, the fourth edition was published by State University of New York Press, Albany.

Pat Parker was an African American poet and activist. Both her poetry and her activism drew from her experiences as a Black lesbian feminist. Her poetry spoke about her tough childhood growing up in poverty, dealing with sexual assault, and the murder of a sister. At eighteen, Parker was in an abusive relationship and had a miscarriage after being pushed down a flight of stairs. After two divorces, she came out as a lesbian, "embracing her sexuality" and said she was liberated and "knew no limits when it came to expressing the innermost parts of herself".

Third Woman Press (TWP) is a Queer and Feminist of Color publisher forum committed to feminist and queer of color decolonial politics and projects. It was founded in 1979 by Norma Alarcón in Bloomington, Indiana. She aimed to create a new political class surrounding sexuality, race, and gender. Alarcón wrote that "Third Woman is one forum, for the self-definition and the self-invention which is more than reformism, more than revolt. The title Third Woman refers to that pre-ordained reality that we have been born to and continues to live and experience and be a witness to, despite efforts toward change ..."

The Erotic, is a concept of a source of power and resources that are available within all humans, which draw on feminine and spiritual approaches to introspection. The erotic was first conceptualized by Audre Lorde in her 1978 essay in Sister Outsider, "Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power". In the essay, Lorde describes the erotic as "the nurturer or nursemaid of our deepest knowledge" and "a lens through which we scrutinize all aspects of our existence". Audre Lorde focuses on the power of the erotic for women, describing how the erotic offers "a well of replenishing and provocative force to the woman who does not fear its revelation, nor succumb to the belief that sensation is enough".

Queer of color critique is an intersectional framework, grounded in Black feminism, that challenges the single-issue approach to queer theory by analyzing how power dynamics associated race, class, gender expression, sexuality, ability, culture and nationality influence the lived experiences of individuals and groups that hold one or more of these identities. Incorporating the scholarship and writings of Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Barbara Smith, Cathy Cohen, Brittney Cooper and Charlene A. Carruthers, the queer of color critique asks: what is queer about queer theory if we are analyzing sexuality as if it is removed from other identities? The queer of color critique expands queer politics and challenges queer activists to move out of a "single oppression framework" and incorporate the work and perspectives of differently marginalized identities into their politics, practices and organizations. The Combahee River Collective Statement clearly articulates the intersecting forces of power: "The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives." Queer of color critique demands that an intersectional lens be applied queer politics and illustrates the limitations and contradictions of queer theory without it. Exercised by activists, organizers, intellectuals, care workers and community members alike, the queer of color critique imagines and builds a world in which all people can thrive as their most authentic selves- without sacrificing any part of their identity.

Black lesbian literature is a subgenre of lesbian literature and African American literature that focuses on the experiences of black women who identify as lesbians. The genre features poetry and fiction about black lesbian characters as well as non-fiction essays which address issues faced by black lesbians. Prominent figures within the genre include Ann Allen Shockley, Audre Lorde, Cheryl Clarke, and Barbara Smith.

All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave (1982) is a landmark feminist anthology in Black Women's Studies printed in numerous editions, co-edited by Akasha Gloria Hull, Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith.

Persephone Press was a publishing company and communications network run by a lesbian-feminist collective in Watertown, Massachusetts. The company published fourteen books between 1976 and 1983, when the organization was sold to Beacon Press.