Haiku (俳句)listen (help·info) is a very short form of Japanese poetry in three phrases, typically characterized by three qualities:

- The essence of haiku is "cutting" (kiru). This is often represented by the juxtaposition of two images or ideas and a kireji between them, a kind of verbal punctuation mark which signals the moment of separation and colours the manner in which the juxtaposed elements are related.

- Traditional haiku often consist of 17 on, in three phrases of 5, 7, and 5 on, respectively.

- A kigo, usually drawn from a saijiki, an extensive but defined list of such terms.

Natsume Sōseki, born Natsume Kin'nosuke, was a Japanese novelist. He is best known for his novels Kokoro, Botchan, I Am a Cat and his unfinished work Light and Darkness. He was also a scholar of British literature and composer of haiku, kanshi, and fairy tales. From 1984 until 2004, his portrait appeared on the front of the Japanese 1000 yen note. In Japan, he is often considered the greatest writer in modern Japanese history. He has had a profound effect on almost all important Japanese writers since.

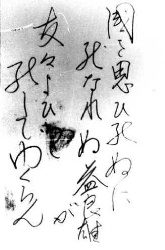

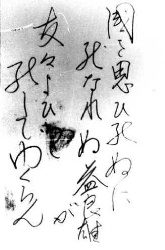

The death poem is a genre of poetry that developed in the literary traditions of East Asian cultures—most prominently in Japan as well as certain periods of Chinese history and Joseon Korea. They tend to offer a reflection on death—both in general and concerning the imminent death of the author—that is often coupled with a meaningful observation on life. The practice of writing a death poem has its origins in Zen Buddhism. It is a concept or worldview derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence, specifically that the material world is transient and impermanent, that attachment to it causes suffering, and ultimately all reality is an emptiness or absence of self-nature. These poems became associated with the literate, spiritual, and ruling segments of society, as they were customarily composed by a poet, warrior, nobleman, or Buddhist monk.

Renku, or haikai no renga, is a Japanese form of popular collaborative linked verse poetry. It is a development of the older Japanese poetic tradition of ushin renga, or orthodox collaborative linked verse. At renku gatherings participating poets take turns providing alternating verses of 17 and 14 morae. Initially haikai no renga distinguished itself through vulgarity and coarseness of wit, before growing into a legitimate artistic tradition, and eventually giving birth to the haiku form of Japanese poetry. The term renku gained currency after 1904, when Kyoshi Takahama started to use it.

Saihō-ji (西芳寺) is a Rinzai Zen Buddhist temple located in Matsuo, Nishikyō Ward, Kyoto, Japan. The temple, which is famed for its moss garden, is commonly referred to as "Koke-dera" (苔寺), meaning "moss temple", while the formal name is "Kōinzan Saihō-ji" (洪隠山西芳寺). The temple, primarily constructed to honor Amitābha, was first founded by Gyōki and was later restored by Musō Soseki. In 1994, Saihō-ji was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as part of the "Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto". Over 120 types of moss are present in the two-tiered garden, resembling a beautiful green carpet with many subtle shades.

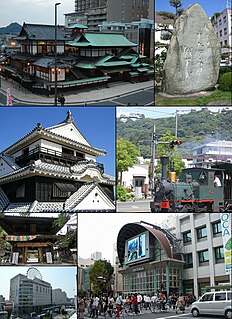

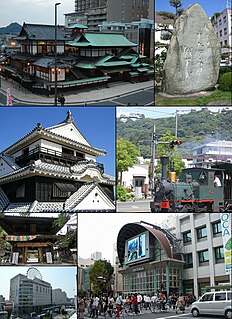

Matsuyama is the capital city of Ehime Prefecture on the island of Shikoku in Japan and also Shikoku's largest city, with a population of 516,459 as of December 1, 2014. It is located on the northeastern portion of the Dōgo Plain. Its name means "pine mountain". The city was founded on December 15, 1889.

Wumen Huikai (1183–1260) was a Chinese Chán master during China´s Song period. He is most famous for having compiled and commentated the 48-koan collection The Gateless Barrier.

Katsu is a shout that is described in Chán and Zen Buddhism encounter-stories, to expose the enlightened state of the Zen-master, and/or to induce initial enlightenment experience in a student. The shout is also sometimes used in the East Asian martial arts for a variety of purposes; in this context, katsu is very similar to the shout kiai.

Gidō Shūshin, 1325–1388), Japanese luminary of the Zen Rinzai sect, was a master of poetry and prose in Chinese. Gidō’s own diary relates how as a child he discovered and treasured the Zen classic Rinzairoku in his father’s library. He was born in Tosa on the island of Shikoku and began formal study of Confucian and Buddhist literature. His religious proclivities were encouraged when he witnessed the violent death of a clan member. Like many others he took his first vows on Mt. Hiei near the capital. Gidō’s life was changed with a visit to the prominent Zen master Musō Soseki (1275–1351) in 1341. He would become the master’s attendant after his own unsuccessful pilgrimage to China. He would become a principal disciple. Gidō was born with eyesight difficulties. His choice of a literary name was Kūgedojin or Holy Man who sees Flowers in the Sky. Kūge was from Sanscrit khpuspa and indicated illusory sense perceptions. Gidō would play a role of conciliator between rival courts in the nation’s civil war. His loyalty was with the northern court and its Ashikaga supporters. After taking residence in the city of Kamakura, Gidō would become the personal advisor to the Ashikaga rulers there. Gidō encouraged Confucian political values such as centralized rule and social stability. Likewise Gidō became an advocate of Sung period Chinese Neo-Confucian humanistic values, both political and literary. In 1380 Gidō was asked by the reigning shōgun, Yoshimitsu (1358–1408), to reside with him in Kyoto. Gidō’s last years were spent personally instructing Yoshimitsu in Confucian and Buddhist subjects.

Hiroaki Sato is a Japanese poet and prolific translator who writes frequently for The Japan Times. He has been called "perhaps the finest translator of contemporary Japanese poetry into American English".

Kyoshi Takahama was a Japanese poet active during the Shōwa period of Japan. His real name was Takahama Kiyoshi (高浜清); Kyoshi was a pen name given to him by his mentor, Masaoka Shiki.

Lanxi Daolong, born in Sichuan Province, China in 1213 A.D., was a famous Chinese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, idealist philosopher, and is the founder of the Kenchō-ji sect, which is a branch of the Rinzai school.

Hototogisu is a Japanese literary magazine focusing primarily on haiku. Founded in 1897, it was responsible for the spread of modern haiku among the Japanese public and is now Japan's most prestigious and long-lived haiku periodical.

Shunmyō Masuno is a Japanese monk and garden designer. He is chief priest of the Sōtō Zen temple Kenkō-ji, professor at Tama Art University, and president of a design firm that has completed numerous projects in Japan and overseas. He has been called "Japan's leading garden designer".

Natsume Sōseki wrote many poems in Classical Chinese (kanshi) during his career. He began writing Chinese in school, and continued throughout his life, but became especially prolific just before his death. His kanshi are well-regarded critically – in fact considered the best of the Meiji period – but are not as popular as his novels.