Sextus Julius Frontinus was a Roman civil engineer, author, soldier and senator of the late 1st century AD. He was a successful general under Domitian, commanding forces in Roman Britain, and on the Rhine and Danube frontiers. A novus homo, he was consul three times. Frontinus ably discharged several important administrative duties for Nerva and Trajan. However, he is best known to the post-Classical world as an author of technical treatises, especially De aquaeductu, dealing with the aqueducts of Rome.

The ancient Romans were the first civilization to build large, permanent bridges. Early Roman bridges used techniques introduced by Etruscan immigrants, but the Romans improved those skills, developing and enhancing methods such as arches and keystones. There were three major types of Roman bridge: wooden, pontoon, and stone. Early Roman bridges were wooden, but by the 2nd century BC stone was being used. Stone bridges used the arch as their basic structure, and most used concrete, the first use of this material in bridge-building.

The Aniene, formerly known as the Teverone, is a 99-kilometer (62 mi) river in Lazio, Italy. It originates in the Apennines at Trevi nel Lazio and flows westward past Subiaco, Vicovaro, and Tivoli to join the Tiber in northern Rome. It formed the principal valley east of ancient Rome and became an important water source as the city's population expanded. The falls at Tivoli were noted for their beauty. Historic bridges across the river include the Ponte Nomentano, Ponte Mammolo, Ponte Salario, and Ponte di San Francesco, all of which were originally fortified with towers.

The Aqua Appia was the first Roman aqueduct, and its construction was begun in 312 BC by the censor Appius Claudius Caecus, who also built the important Via Appia. By the end of the 1st century BC it had fallen out of use as an aqueduct, and was used as a sewer instead.

The Aqua Augusta, or Serino Aqueduct, was one of the largest, most complex and costliest aqueduct systems in the Roman world; it supplied water to at least eight ancient cities in the Bay of Naples including Pompeii and Herculaneum. This aqueduct was unlike any other of its time, being a regional network rather than being focused on one urban centre.

The Romans constructed aqueducts throughout their Republic and later Empire, to bring water from outside sources into cities and towns. Aqueduct water supplied public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households; it also supported mining operations, milling, farms, and gardens.

Aqua Anio Novus was an ancient Roman aqueduct supplying the city of Rome. Like the Aqua Claudia, it was begun by emperor Caligula in 38 AD and completed in 52 AD by Claudius, who dedicated them both on August 1.

Aqua Claudia was an ancient Roman aqueduct that, like the Aqua Anio Novus, was begun by Emperor Caligula in 38 AD and finished by Emperor Claudius in 52 AD.

The Aqua Julia is a Roman aqueduct built in 33 BC by Agrippa under Augustus to supply the city of Rome. It was repaired and expanded by Augustus from 11–4 BC.

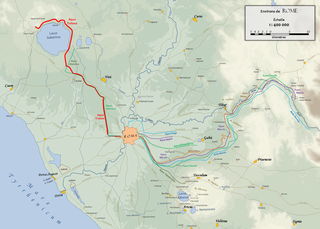

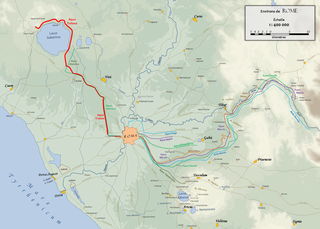

The Aqua Traiana was a 1st-century Roman aqueduct built by Emperor Trajan and inaugurated in 109 AD. It channelled water from sources around Lake Bracciano, 40 km (25 mi) north-west of Rome, to ancient Rome. It joined the earlier Aqua Alsietina to share a common lower route into Rome.

The Aqua Tepula is an ancient Roman aqueduct completed in 125 BC by censors Gnaeus Servilius Caepio, who had served as consul in 141 BC, and Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla.

In Ancient Rome, the Aqua Alsietina was the earlier of the two western Roman aqueducts, erected sometime around 2 BC, during the reign of emperor Augustus. It was the only water supply for the Transtiberine region, on the right bank of the river Tiber until the Aqua Traiana was built.

The Via Sublacensis was a Roman road constructed to connect Nero's palace in present-day Subiaco to Rome, splitting off from the Via Valeria near Varia, about 10 km northeast of Tivoli.

De aquaeductu is a two-book official report given to the emperor Nerva or Trajan on the state of the aqueducts of Rome, and was written by Sextus Julius Frontinus at the end of the 1st century AD. It is also known as De Aquis or De Aqueductibus Urbis Romae. It is the earliest official report of an investigation made by a distinguished citizen on Roman engineering works to have survived. Frontinus had been appointed Water Commissioner by the emperor Nerva in AD 96.

The Aqua Marcia is one of the longest of the eleven aqueducts that supplied the city of Rome. The aqueduct was built between 144–140 BC, during the Roman Republic. The still-functioning Acqua Felice from 1586 runs on long stretches along the route of the Aqua Marcia.

The Aqueduct of the Gier is an ancient Roman aqueduct probably constructed in the 1st century AD to provide water for Lugdunum (Lyon), in what is now eastern France. It is the longest and best preserved of four Roman aqueducts that served the growing capital of the Roman province of Gallia Lugdunensis. It drew its water from the source of the Gier, a small tributary of the Rhone, on the slopes of Mont Pilat, 42 km (26 mi) south-west of Lyon.

Aqueducts are bridges constructed to convey watercourses across gaps such as valleys or ravines. The term aqueduct may also be used to refer to the entire watercourse, as well as the bridge. Large navigable aqueducts are used as transport links for boats or ships. Aqueducts must span a crossing at the same level as the watercourses on each end. The word is derived from the Latin aqua ("water") and ducere, therefore meaning "to lead water". A modern version of an aqueduct is a pipeline bridge. They may take the form of tunnels, networks of surface channels and canals, covered clay pipes or monumental bridges.

Quintus Marcius Rex was a Roman politician of the Marcii Reges, a patrician family of gens Marcia, who claimed royal descent from the Roman King Ancus Marcius. He was a maternal great-grandfather of Julius Caesar.

Municipio Roma VII is the seventh administrative subdivision of the Municipality of Rome (Italy).