Eärendil the Mariner and his wife Elwing are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. They are depicted in The Silmarillion as Half-elven, the children of Men and Elves. He is a great seafarer who, on his brow, carried the morning star, a jewel called a Silmaril, across the sky. The jewel had been saved by Elwing from the destruction of the Havens of Sirion. The morning star and the Silmarils are elements of the symbolism of light, for divine creativity, continually splintered as history progresses. Tolkien took Eärendil's name from the Old English name Earendel, found in the poem Crist A, which hailed him as "brightest of angels"; this was the beginning of Tolkien's Middle-earth mythology. Elwing is the granddaughter of Lúthien and Beren, and is descended from Melian the Maia. Through their progeny, Eärendil and Elwing became the ancestors of the Númenorean, and later Dúnedain, royal bloodline.

A Balrog is a powerful fictional demonic monster in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth. One first appeared in print in his high fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings, where the Fellowship of the Ring encounter a Balrog known as Durin's Bane in the Mines of Moria. Balrogs appear also in Tolkien's The Silmarillion and other posthumously published books. Balrogs are tall and menacing beings who can shroud themselves in fire, darkness, and shadow. They are armed with fiery whips "of many thongs", and occasionally use long swords.

In the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Noldor are a kindred of High Elves who migrated to Valinor from Middle-earth and lived in Eldamar, the coastal region of Aman, a continent that lay west of Middle-earth. The majority of the Noldor returned to Beleriand in the northwest of Middle-earth following the murder of their first leader Finwë by the Dark Lord Morgoth, on the instigation of Finwë's eldest son Fëanor. They were the second clan of the Elves in both order and size, the other clans being the Vanyar and the Teleri.

Fëanor is a fictional character from J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium who plays an important part in The Silmarillion as the creator of the three Silmarils, the skilfully-forged jewels that give the book their name and theme. He was the eldest son of Finwë, the King of the Noldor, and his first wife Míriel Serindë.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional legendarium, Beleriand was a region in northwestern Middle-earth during the First Age. Events in Beleriand are described chiefly in his work The Silmarillion, which tells the story of the early ages of Middle-earth in a style similar to the epic hero tales of Nordic literature. Beleriand also appears in the works The Book of Lost Tales, The Children of Húrin, and in the epic poems of The Lays of Beleriand.

Lúthien and Beren are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world Middle-earth. Lúthien is an elf, daughter of Thingol and Melian. Beren is a mortal man. The complex tale of their love for each other and the quest they are forced to embark upon, triumphing against overwhelming odds but ending in tragedy, appears in The Silmarillion, the epic poem The Lay of Leithian, the Grey Annals section of The War of the Jewels, and in other legendarium texts conflated into the 2017 book Beren and Lúthien, where it plays a central part. Their story is told to Frodo by Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings.

Fingolfin is a character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, appearing in The Silmarillion. He was the son of Finwë, High King of the Noldor. He was threatened by his half-brother Fëanor, who held him in contempt for not being a pure-bred Noldor. Even so, when Fëanor stole ships and left Aman, Fingolfin chose to follow him back to Middle-earth, taking the dangerous route over the ice of the Helcaraxë. On arrival, he challenged the Dark Lord Morgoth at the gates of his fortress, Angband, but Morgoth stayed inside. When his son Fingon rescued Maedhros, son of Fëanor, Maedhros gratefully renounced his claim to kingship, and Fingolfin became High King of the Noldor. He was victorious at the battle of Dagor Aglareb, and there was peace for some 400 years until Morgoth broke out and destroyed Beleriand in the Dagor Bragollach. Fingolfin, receiving false news, rode alone to Angband and challenged Morgoth to single combat. He wounded Morgoth several times, but grew weary and was killed by the immortal Vala.

Maedhros is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, first introduced as a major character in The Silmarillion and later mentioned in Unfinished Tales and The Children of Húrin. In the books, Maedhros was the first son of Fëanor, the creator of the Silmarils that were essential to the plot and the history of Middle-earth. Following his father in swearing to reclaim the Silmarils from anyone who took and kept them, he led his people the Noldor in their war against Morgoth in Middle-earth, and brought eventual ruin upon himself and his brothers. Maedhros has been the subject of artwork by artists such as Jenny Dolfen and Alan Lee.

Túrin Turambar is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. "Turambar and the Foalókë", begun in 1917, is the first appearance of Túrin in the legendarium. J. R. R. Tolkien consciously based the story on the medieval tale of Kullervo in the Finnish mythological poem Kalevala compiled by Elias Lönnrot, saying that it was "an attempt to reorganize...the tale of Kullervo the hapless, into a form of my own". Also called "The Tale of Grief" and "Narn i Chîn Húrin", it tells of the tragic fates of the children of Húrin, namely his son Túrin (Turambar) and his daughter Nienor. Excerpts of the story have been published over the years, in The Silmarillion (prose), Unfinished Tales (prose), The Book of Lost Tales Part II (prose), The Lays of Beleriand and most recently in 1994 in The War of the Jewels (prose), the latter three part of The History of Middle-earth series.

Tuor Eladar and Idril Celebrindal are fictional characters from J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. They are the parents of Eärendil the Mariner and grandparents of Elrond Half-elven: through their progeny, they became the ancestors of the Númenoreans and of the King of the Reunited Kingdom Aragorn Elessar. Both characters play a pivotal role in The Fall of Gondolin, one of Tolkien's earliest stories which formed the basis for a section in his later work, The Silmarillion, and later expanded and released as a standalone publication in 2018.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional universe of Middle-earth, the eagles were immense flying birds that were sapient and could speak. Often emphatically referred to as the Great Eagles, they appear, usually and intentionally serving as agents of eucatastrophe or deus ex machina, in his legendarium, from The Silmarillion and the accounts of Númenor to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Weapons and armour of Middle-earth are those of J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth fantasy writings, such as The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion.

The fictional races and peoples that appear in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world of Middle-earth include the seven listed in Appendix F of The Lord of the Rings: Elves, Men, Dwarves, Hobbits, Ents, Orcs and Trolls, as well as spirits such as the Valar and Maiar. Other beings of Middle-earth are of unclear nature such as Tom Bombadil and his wife Goldberry.

Fáfnismál is an Eddic poem, found in the Codex Regius manuscript. The poem is unnamed in the manuscript, where it follows Reginsmál and precedes Sigrdrífumál, but modern scholars regard it as a separate poem and have assigned it a name for convenience.

The Children of Húrin is an epic fantasy novel which forms the completion of a tale by J. R. R. Tolkien. He wrote the original version of the story in the late 1910s, revised it several times later, but did not complete it before his death in 1973. His son, Christopher Tolkien, edited the manuscripts to form a consistent narrative, and published it in 2007 as an independent work. The book contains 33 illustrations by Alan Lee, eight of which are full-page and in colour. The story is one of three "great tales" set in the First Age of Tolkien's Middle-earth, the other two being Beren and Lúthien and The Fall of Gondolin.

Mirkwood is a name used for a great dark fictional forest in novels by Sir Walter Scott and William Morris in the 19th century, and by J. R. R. Tolkien in the 20th century. The critic Tom Shippey explains that the name evoked the excitement of the wildness of Europe's ancient North.

The Maiar are a fictional class of beings from J. R. R. Tolkien's high fantasy legendarium. Supernatural and angelic, they are "lesser Ainur" who entered the cosmos of Eä in the beginning of time. The name Maiar is in the Quenya tongue from the Elvish root maya- "excellent, admirable".

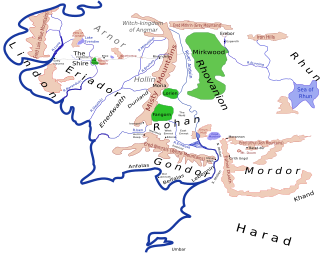

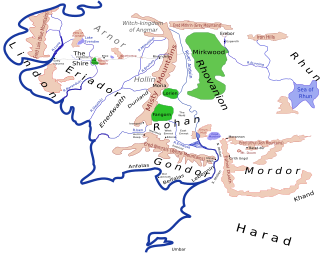

Middle-earth is the fictional setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the Miðgarðr of Norse mythology and Middangeard in Old English works, including Beowulf. Middle-earth is the human-inhabited world, that is, the central continent of the Earth, in Tolkien's imagined mythological past. Tolkien's most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, are set entirely in Middle-earth. "Middle-earth" has also become a short-hand term for Tolkien's legendarium, his large body of fantasy writings, and for the entirety of his fictional world.

Morgoth Bauglir is a character, one of the godlike Valar, from Tolkien's legendarium. He is the main antagonist of The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien and The Fall of Gondolin.

Tolkien's monsters are the evil beings, such as Orcs, Trolls, and giant spiders, who oppose and sometimes fight the protagonists in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. Tolkien was an expert on Old English, especially Beowulf, and several of his monsters share aspects of the Beowulf monsters; his Trolls have been likened to Grendel, the Orcs' name harks back to the poem's orcneas, and the dragon Smaug has multiple attributes of the Beowulf dragon. The European medieval tradition of monsters makes them either humanoid but distorted, or like wild beasts, but very large and malevolent; Tolkien follows both traditions, with monsters like Orcs of the first kind and Wargs of the second. Some scholars add Tolkien's immensely powerful Dark Lords Morgoth and Sauron to the list, as monstrous enemies in spirit as well as in body. Scholars have noted that the monsters' evil nature reflects Tolkien's Roman Catholicism, a religion which has a clear conception of good and evil.