Quetzalcoatlus is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur known from the Late Cretaceous Maastrichtian age of North America. Its name comes from the Aztec feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl. The type species is Q. northropi, named by Douglas Lawson in 1975. The genus also includes the smaller species Q. lawsoni, which was known for many years as an unnamed species, before being named by Brian Andres and Wann Langston Jr. (posthumously) in 2021. Q. northropi has gained fame as a candidate for the largest flying animal ever discovered.

Magyarosaurus is a genus of dwarf sauropod dinosaur from late Cretaceous Period in Romania. It is one of the smallest-known adult sauropods, measuring only 6 m (20 ft) in length and 750–1,000 kg (1,650–2,200 lb) in body mass. The type and only certain species is Magyarosaurus dacus. It has been found to be a close relative of Rapetosaurus in the family Saltasauridae in the sauropod clade Titanosauria in a 2005 study.

Azhdarchidae is a family of pterosaurs known primarily from the Late Cretaceous Period, though an isolated vertebra apparently from an azhdarchid is known from the Early Cretaceous as well. Azhdarchids are mainly known for including some of the largest flying animals discovered, but smaller cat-size members have also been found. Originally considered a sub-family of Pteranodontidae, Nesov (1984) named the Azhdarchinae to include the pterosaurs Azhdarcho, Quetzalcoatlus, and Titanopteryx. They were among the last known surviving members of the pterosaurs, and were a rather successful group with a worldwide distribution. Previously it was thought that by the end of the Cretaceous, most pterosaur families except for the Azhdarchidae disappeared from the fossil record, but recent studies indicate a wealth of pterosaurian fauna, including pteranodontids, nyctosaurids, tapejarids and several indeterminate forms. In several analyses, some taxa such as Navajodactylus, Bakonydraco and Montanazhdarcho were moved from Azhdarchidae to other clades.

Arambourgiania is an extinct genus of azhdarchid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of Jordan, and possibly the United States. Arambourgiania was among the largest members of its family, the Azhdarchidae, and it is also one of the largest flying animals ever known. The incomplete left ulna of the "Sidi Chennane azhdarchid" from Morocco may have also belonged to Arambourgiania.

Hațeg Island was a large offshore island in the Tethys Sea which existed during the Late Cretaceous period, probably from the Cenomanian to the Maastrichtian ages. It was situated in an area corresponding to the region around modern-day Hațeg, Hunedoara County, Romania. Maastrichtian fossils of small-sized dinosaurs have been found in the island's rocks. It was formed mainly by tectonic uplift during the early Alpine orogeny, caused by the collision of the African and Eurasian plates towards the end of the Cretaceous. There is no real present-day analog, but overall, the island of Hainan is perhaps closest as regards climate, geology and topography, though still not a particularly good match. The vegetation, for example, was of course entirely distinct from today, as was the fauna.

Hatzegopteryx is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur found in the late Maastrichtian deposits of the Densuş Ciula Formation, an outcropping in Transylvania, Romania. It is known only from the type species, Hatzegopteryx thambema, named by Buffetaut et al. in 2002 based on parts of the skull and humerus. Additional specimens, including a neck vertebra, were later placed in the genus, representing a range of sizes. The largest of these remains indicate it was among the biggest pterosaurs, with an estimated wingspan of 10 to 12 metres.

Montanazhdarcho is a genus of azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of what is now the state of Montana, United States. Montanazhdarcho is known from only one species, M. minor.

Eoazhdarcho is a genus of azhdarchoid pterodactyloid pterosaur named in 2005 by Chinese paleontologists Lü Junchang and Ji Qiang. The type and only known species is Eoazhdarcho liaoxiensis. The fossil was found in the Aptian-age Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Chaoyang, Liaoning, China.

Phosphatodraco is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous of what is now Morocco. In 2000, a pterosaur specimen consisting of five cervical (neck) vertebrae was discovered in the Ouled Abdoun Phosphatic Basin. The specimen was made the holotype of the new genus and species Phosphatodraco mauritanicus in 2003; the genus name means "dragon from the phosphates", and the specific name refers to the region of Mauretania. Phosphatodraco was the first Late Cretaceous pterosaur known from North Africa, and the second pterosaur genus described from Morocco. It is one of the only known azhdarchids preserving a relatively complete neck, and was one of the last known pterosaurs. Additional cervical vertebrae have since been assigned to the genus, and it has been suggested that fossils of the pterosaur Tethydraco represent wing elements of Phosphatodraco.

Aralazhdarcho is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur from the Santonian to the early Campanian stages of the Late Cretaceous period of Bostobe Svita in Kazakhstan. The type and only known species is Aralazhdarcho bostobensis.

Elanodactylus is a genus of ctenochasmatid pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous period of what is now the Yixian Formation of Liaoning, China.

Volgadraco is a genus of pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of European Russia. Volgadraco was originally classified as an azhdarchid. However, recent studies have concluded that it may belong to either the family Nyctosauridae, or the family Pteranodontidae.

Alanqa is a genus of pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of what is now the Kem Kem Beds of southeastern Morocco. The name Alanqa comes from the Arabic word العنقاءal-‘Anqā’, for a mythical bird of Arabian culture.

Paludititan is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur which lived in the area of present Romania during the Late Cretaceous. It existed in the island ecosystem known as Hațeg Island.

Aerotitan is a genus of large azhdarchid pterosaur known from the Late Cretaceous period of what is now the Allen Formation of the Neuquén Basin in northern Patagonia, Argentina.

Mistralazhdarcho is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of France. The type and only species is Mistralazhdarcho maggii.

Cryodrakon is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period in what is now Canada. It contains a single species, Cryodrakon boreas, recovered from the Dinosaur Park Formation.

The Sebeș Formation is a geological formation in Romania. It is of Maastrichtian age. It is laterally equivalent to the Sard Formation. The base of the formation consists of claystones interbedded with sandstones and conglomerates. It is well known for its fossils which form a component of the Hațeg Island fauna.

Albadraco is an azhdarchid pterosaur genus that during the Late Cretaceous lived in the area of modern Romania. The type species is Albadraco tharmisensis.

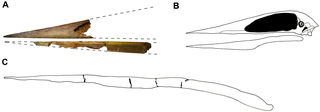

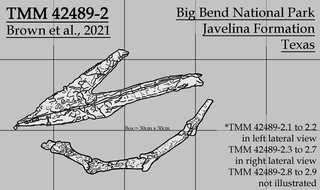

Wellnhopterus is an azhdarchid pterosaur recovered from the Late Cretaceous Javelina Formation in Texas that was previously identified as a thalassodromine. It consists of a set of upper and lower jaws, as well as some cervical vertebrae and a fragmentary long bone. In July 2021, the jaws were given the genus name "Javelinadactylus", with the type and only species as "J. sagebieli"; however, this article has now been retracted. In a paper published in December 2021, the complete holotype was independently named Wellnhopterus, with the only species being W. brevirostris. As of 2022, this is the formal name of this pterosaur.