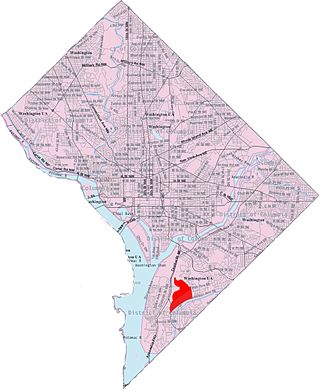

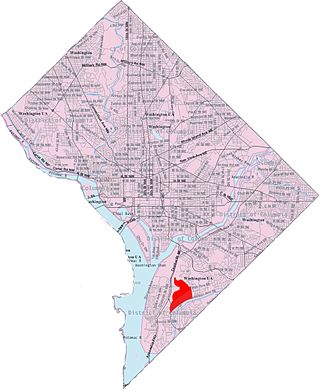

Anacostia is a historic neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C. Its downtown is located at the intersection of Good Hope Road and Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. It is located east of the Anacostia River, after which the neighborhood is named.

Anacostia station is a Washington Metro station in Washington, D.C., on the Green Line. The station is located in the Anacostia neighborhood of Southeast Washington, with entrances at Shannon Place and Howard Road near Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue SE. The station serves as a hub for Metrobus routes in Southeast, Washington, D.C., and Prince George's County, Maryland.

Southeast is the southeastern quadrant of Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States, and is located south of East Capitol Street and east of South Capitol Street. It includes the Capitol Hill and Anacostia neighborhoods, the Navy Yard, the Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling (JBAB), the U.S. Marine Barracks, the Anacostia River waterfront, Eastern Market, the remains of several Civil War-era forts, historic St. Elizabeths Hospital, RFK Stadium, Nationals Park, and the Congressional Cemetery. It also contains a landmark known as "The Big Chair," located on Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. The quadrant is split by the Anacostia River, with the portion that is west of the river sometimes referred to as "Near Southeast". Geographically, it is the second-smallest quadrant of the city.

Benning Road is a major traveled street in Washington, D.C., and Prince George's County, Maryland.

Congress Heights is a residential neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C., in the United States. The irregularly shaped neighborhood is bounded by the St. Elizabeths Hospital campus, Lebaum Street SE, 4th Street SE, and Newcomb Street SE on the northeast; Shepard Parkway and South Capitol Street on the west; Atlantic Street SE and 1st Street SE on the south; Oxon Run Parkway on the southeast; and Wheeler Street SE and Alabama Avenue SE on the east. Commercial development is heavy along Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue and Malcolm X Avenue.

South Capitol Street is a major street dividing the southeast and southwest quadrants of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It runs south from the United States Capitol to the D.C.–Maryland line, intersecting with Southern Avenue. After it enters Maryland, the street becomes Indian Head Highway at the Eastover Shopping Center, a terminal or transfer point of many bus routes.

The 11th Street Bridges are a complex of three bridges across the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., United States. The bridges convey Interstate 695 across the Anacostia to its southern terminus at Interstate 295 and DC 295. The bridges also connect the neighborhood of Anacostia with the rest of the city of Washington.

Barney Circle is a small residential neighborhood located between the west bank of the Anacostia River and the eastern edge of Capitol Hill in southeast Washington, D.C., in the United States. The neighborhood is characterized by its sense of community, activism, walkability, and historic feel. The neighborhood's name derives from the eponymous former traffic circle Pennsylvania Avenue SE just before it crosses the John Philip Sousa Bridge over the Anacostia. The traffic circle is named for Commodore Joshua Barney, Commander of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla in the War of 1812.

Hillcrest is a residential neighborhood in the southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C., United States. Hillcrest is located on the District-Maryland line in Ward 7, east of the Anacostia River.

Good Hope is a residential neighborhood in southeast Washington, D.C., near Anacostia. The neighborhood is generally middle class and is dominated by single-family detached and semi-detached homes. The year-round Fort Dupont Ice Arena skating rink and the Smithsonian Institution's Anacostia Museum are nearby. Good Hope is bounded by Fort Stanton Park to the north, Alabama Avenue SE to the south, Naylor Road SE to the west, and Branch Avenue SE to the east. The proposed Skyland Shopping Center redevelopment project is within the boundaries of the neighborhood.

Greenway is a residential neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C., in the United States. The neighborhood is bounded by East Capitol Street to the north, Pennsylvania Avenue SE to the south, Interstate 295 to the west, and Minnesota Avenue to the east.

The Pennsylvania Avenue Line, designated Routes 32 and 36, is a daily Metrobus route in Washington, D.C., Operating between the Southern Avenue station or Naylor Road station of the Green Line of the Washington Metro and Potomac Park. Until the 1960s, it was a streetcar line, opened in 1862 by the Washington and Georgetown Railroad as the first line in the city.

The Anacostia and Potomac River Railroad Company was the fourth streetcar company to operate in Washington, D.C., and the first to cross the Anacostia River. It was chartered in 1870, authorized by Congress in 1875 and built later that year. The line ran from the Arsenal to Union Town. It expanded, adding lines to Congressional Cemetery, Central Market and to the Government Hospital for the Insane; and in the late 1890s it purchased two other companies and expanded their lines. It was reluctant to change its operations, but in 1900 it relented to pressure and became the last company to switch from horsecars to electric streetcars. It was one of the few companies not to be swept up by the two major streetcar companies at the turn of the 20th century, but it could not hold out forever and on August 31, 1912, it was purchased by the Washington Railway and Electric Company and ceased to operate as a unique entity.

The DC Streetcar is a surface streetcar network in Washington, D.C. As of 2017, it consists of only one line: a 2.2-mile (3.5 km) segment running in mixed traffic along H Street and Benning Road in the city's Northeast quadrant.

The Anacostia Historic District is a historic district in the city of Washington, D.C., comprising approximately 20 squares and about 550 buildings built between 1854 and 1930. The Anacostia Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. "The architectural character of the Anacostia area is unique in Washington. Nowhere else in the District of Columbia does there exist such a collection of late-19th and early-20th century small-scale frame and brick working-class housing."

Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue is a major street in the District of Columbia traversing through both the Southwest and Southeast quadrants.

The Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge was a crossing of the Anacostia River in Washington, DC at the site of the present John Philip Sousa Bridge. It was constructed in 1890 and demolished around 1939.

The Anacostia Line is a partially constructed line of the DC Streetcar, never put into service, intended to connect the Anacostia neighborhood with Joint Base Anacostia–Bolling. Construction occurred in 2009 and 2010, but was terminated before the line was complete.

The Chillum Road Line, designated as Route F1 is a daily bus route operated by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority between Cheverly station of the Orange Line of the Washington Metro and Takoma station of the Red Line. The line operates every 25–38 minutes during peak hours, 60 minutes during weekday off peak hours, and 58–62 minutes on the weekends. Trips roughly take 50–60 minutes.

The U Street–Garfield Line, designated Routes 90 and 92, are daily bus routes operated by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority between Anacostia station (90) or Congress Heights station (92) of the Green Line of the Washington Metro and Duke Ellington Bridge (90) in Adams Morgan or Reeves Center / U Street station (92) of the Green Line of the Washington Metro. Late Night & Early Morning 92 trips are extended to Duke Ellington Bridge. The lines operate every 12 - 24 minutes between 7 AM and 9 PM, and 15 - 30 minutes at all other times. Route 90 and 92 trips are roughly 60 to 70 minutes.