Delftware or Delft pottery, also known as Delft Blue or as delf, is a general term now used for Dutch tin-glazed earthenware, a form of faience. Most of it is blue and white pottery, and the city of Delft in the Netherlands was the major centre of production, but the term covers wares with other colours, and made elsewhere. It is also used for similar pottery, English delftware.

Lacquer is a type of hard and usually shiny coating or finish applied to materials such as wood or metal. It is most often made from resin extracted from trees and waxes and has been in use since antiquity.

Decoupage or découpage is the art of decorating an object by gluing colored paper cutouts onto it in combination with special paint effects, gold leaf, and other decorative elements. Commonly, an object like a small box or an item of furniture is covered by cutouts from magazines or from purpose-manufactured papers. Each layer is sealed with varnishes until the "stuck on" appearance disappears and the result looks like painting or inlay work. The traditional technique used 30 to 40 layers of varnish which were then sanded to a polished finish.

Papier-mâché is a versatile craft technique with roots in ancient China, in which waste paper is shredded and mixed with water and a binder to produce a pulp ideal for modelling or moulding, which dries to a hard surface and allows the creation of light, strong and inexpensive objects of any shape, even very complicated ones. There are various recipes, including those using cardboard and some mineral elements such as chalk or clay. Paper-mâché reinforced with textiles or boiled cardboard can be used for durable, sturdy objects. There is even carton-cuir There is also a "laminating process", a method in which strips of paper are glued together in layers. Binding agents include glue, starch or wallpaper paste. "Carton-paille" or strawboard was already described in a book in 1881. Pasteboard is made of whole sheets of paper glued together, or layers of paper pulp pressed together. Millboard is a type of strong pasteboard that contains old rope and other coarse materials in addition to paper.

Lacquerware are objects decoratively covered with lacquer. Lacquerware includes small or large containers, tableware, a variety of small objects carried by people, and larger objects such as furniture and even coffins painted with lacquer. Before lacquering, the surface is sometimes painted with pictures, inlaid with shell and other materials, or carved. The lacquer can be dusted with gold or silver and given further decorative treatments.

Chinoiserie is the European interpretation and imitation of Chinese and other Sinosphere artistic traditions, especially in the decorative arts, garden design, architecture, literature, theatre, and music. The aesthetic of chinoiserie has been expressed in different ways depending on the region. It is related to the broader current of Orientalism, which studied Far East cultures from a historical, philological, anthropological, philosophical, and religious point of view. First appearing in the 17th century, this trend was popularized in the 18th century due to the rise in trade with China and the rest of East Asia.

Plating is a finishing process in which a metal is deposited on a surface. Plating has been done for hundreds of years; it is also critical for modern technology. Plating is used to decorate objects, for corrosion inhibition, to improve solderability, to harden, to improve wearability, to reduce friction, to improve paint adhesion, to alter conductivity, to improve IR reflectivity, for radiation shielding, and for other purposes. Jewelry typically uses plating to give a silver or gold finish.

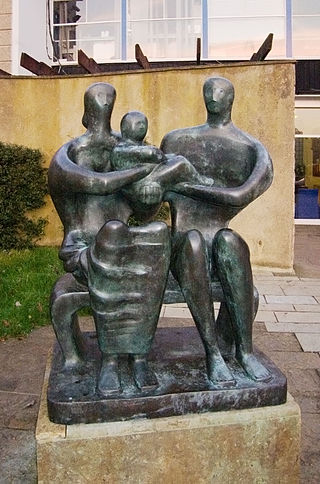

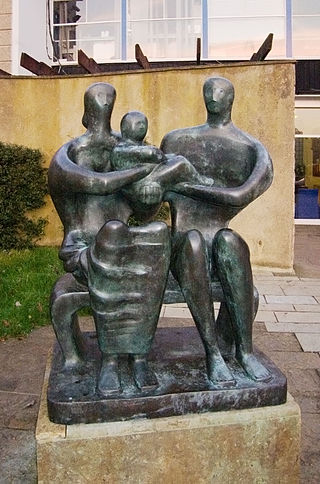

Wolverhampton Art Gallery is located in Wolverhampton, England. The building was funded and constructed by local contractor Philip Horsman (1825–1890), and built on land provided by the municipal authority. It opened in May 1884.

In French interior design, vernis Martin is a type of japanning or imitation lacquer named after the 18th century French Martin brothers: Guillaume, Etienne-Simon, Robert and Julien. They ran a leading factory from between about 1730 and 1770, and were vernisseurs du roi. But they did not invent the process, nor were they the only producers, nor does the term cover a single formula or technique. It imitated Chinese lacquer and European subjects, and was applied to a wide variety of items, from furniture to coaches. It is said to have been made by heating oil and copal and then adding Venetian turpentine.

Lacquerware is a Japanese craft with a wide range of fine and decorative arts, as lacquer has been used in urushi-e, prints, and on a wide variety of objects from Buddha statues to bento boxes for food.

Pontypool japan is a name given to the process of japanning with the use of an oil varnish and heat, which is credited to Thomas Allgood of Pontypool. In the late 17th century, during his search for a corrosion-resistant coating for iron, he developed a recipe that included asphaltum, linseed oil and burnt umber. Once applied to metal and heated the coating turned black and was extremely tough and durable.

Mander Brothers was a major employer in the city of Wolverhampton, in the English Midlands, a progressive company founded in 1773. In the 19th century the firm became the number one manufacturers of varnishes, paints and later printing inks in the British Empire. In the twentieth century it developed its product range in industrial coatings and inks, as well as commercial property.

Coromandel lacquer is a type of Chinese lacquerware, latterly mainly made for export, so called only in the West because it was shipped to European markets via the Coromandel coast of south-east India, where the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) and its rivals from a number of European powers had bases in the 18th century. The most common type of object made in the style, both for Chinese domestic use and exports was the Coromandel screen, a large folding screen with as many as twelve leaves, coated in black lacquer with large pictures using the kuan cai technique, sometimes combined with mother of pearl inlays. Other pieces made include chests and panels.

Lacquer painting is a form of painting with lacquer which was practised in East Asia for decoration on lacquerware, and found its way to Europe and the Western World both via Persia and the Middle East and by direct contact with Continental Asia. The artistic form was revived and developed as a distinct genre of fine art painting by Vietnamese artists in the 1930s; the genre is known in Vietnamese as "sơn mài."

China painting, or porcelain painting, is the decoration of glazed porcelain objects such as plates, bowls, vases or statues. The body of the object may be hard-paste porcelain, developed in China in the 7th or 8th century, or soft-paste porcelain, developed in 18th-century Europe. The broader term ceramic painting includes painted decoration on lead-glazed earthenware such as creamware or tin-glazed pottery such as maiolica or faience.

Chemical coloring of metals is the process of changing the color of metal surfaces with different chemical solutions.

Mexican lacquerware is one of the country's oldest crafts, having independent origins from Asian lacquerware. In the pre-colonial period, a greasy substance from the aje larvae and/or oil from the chia seed were mixed with powdered minerals to create protective coatings and decorative designs. During this period, the process was almost always applied to dried gourds, especially to make the cups that Mesoamerican nobility drank chocolate from. After the Conquest, the Spanish had indigenous craftsmen apply the technique to European style furniture and other items, changing the decorative motifs and color schemes, but the process and materials remained mostly the same. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the craft waned during armed conflicts and returned, both times with changes to the decorative styles and especially in the 20th century, to production techniques. Today, workshops creating these works are limited to Olinalá, Temalacatzingo and Acapetlahuaya in the state of Guerrero, Uruapan and Pátzcuaro in Michoacán and Chiapa de Corzo in Chiapas.

Jalisco handcrafts and folk art are noted among Mexican handcraft traditions. The state is one of the main producers of handcrafts, which are noted for quality. The main handcraft tradition is ceramics, which has produced a number of known ceramicists, including Jorge Wilmot, who introduced high fire work into the state. In addition to ceramics, the state also makes blown glass, textiles, wood furniture including the equipal chair, baskets, metal items, piteado and Huichol art.

The Museum of Lacquer Art is a museum in Münster, Westphalia devoted to the history of lacquer art. It is the only institution of its kind in the world, with a collection of around 1,000 objects from East Asia, Europe, and the Islamic world from more than two thousand years ago. The current director is art historian Gudrun Bühl. It is owned by BASF Coatings.

Mary Verney known also as Molly, & Mall Klenyg was a British noblewoman best known for having the first instance of recorded use of the word Japan as a verb in English in 1683.