Bitumen is an immensely viscous constituent of petroleum. Depending on its exact composition it can be a sticky, black liquid or an apparently solid mass that behaves as a liquid over very large time scales. In American English, the material is commonly referred to as asphalt. Whether found in natural deposits or refined from petroleum, the substance is classed as a pitch. Prior to the 20th century, the term asphaltum was in general use. The word derives from the Ancient Greek word ἄσφαλτος (ásphaltos), which referred to natural bitumen or pitch. The largest natural deposit of bitumen in the world is the Pitch Lake of southwest Trinidad, which is estimated to contain 10 million tons.

A road is a thoroughfare for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles and pedestrians. Unlike streets, whose primary function is to serve as public spaces, the main function of roads is transportation.

Road transport or road transportation is a type of transport using roads. Transport on roads can be roughly grouped into the transportation of goods and transportation of people. In many countries licensing requirements and safety regulations ensure a separation of the two industries. Movement along roads may be by bike, automobile, bus, truck, or by animal such as horse or oxen. Standard networks of roads were adopted by Romans, Persians, Aztec, and other early empires, and may be regarded as a feature of empires. Cargo may be transported by trucking companies, while passengers may be transported via mass transit. Commonly defined features of modern roads include defined lanes and signage. Various classes of road exist, from two-lane local roads with at-grade intersections to controlled-access highways with all cross traffic grade-separated.

Tarmacadam is a concrete road surfacing material made by combining tar and macadam, patented by Welsh inventor Edgar Purnell Hooley in 1902. It is a more durable and dust-free enhancement of simple compacted stone macadam surfaces invented by Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam in the early 19th century. The terms "tarmacadam" and tarmac are also used for a variety of other materials, including tar-grouted macadam, bituminous surface treatments and modern asphalt concrete.

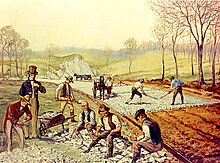

John Loudon McAdam was a Scottish civil engineer and road-builder. He invented a new process, "macadamisation", for building roads with a smooth hard surface, using controlled materials of mixed particle size and predetermined structure, that would be more durable and less muddy than soil-based tracks.

The Shell pavement design method was used in many countries for the design of new pavements made of asphalt. First published in 1963, it was the first mechanistic design method, providing a procedure that was no longer based on codification of historic experience but instead that permitted computation of strain levels at key positions in the pavement. By analyzing different proposed constructions, the procedure allowed a designer to keep the tensile strain at the bottom of the asphalt at a level less than a critical value and to keep the vertical strain at the top of the subgrade less than another critical value. With these two strains kept, respectively, within the design limits, premature fatigue failure in the asphalt and rutting of the pavement would be precluded. Relationships linking strain values to fatigue and rutting permitted a user to design a pavement able to carry almost any desired number of transits of standard wheel loads.

Highway engineering is a professional engineering discipline branching from the civil engineering subdiscipline of transportation engineering that involves the planning, design, construction, operation, and maintenance of roads, highways, streets, bridges, and tunnels to ensure safe and effective transportation of people and goods. Highway engineering became prominent towards the latter half of the 20th century after World War II. Standards of highway engineering are continuously being improved. Highway engineers must take into account future traffic flows, design of highway intersections/interchanges, geometric alignment and design, highway pavement materials and design, structural design of pavement thickness, and pavement maintenance.

A road surface or pavement is the durable surface material laid down on an area intended to sustain vehicular or foot traffic, such as a road or walkway. In the past, gravel road surfaces, macadam, hoggin, cobblestone and granite setts were extensively used, but these have mostly been replaced by asphalt or concrete laid on a compacted base course. Asphalt mixtures have been used in pavement construction since the beginning of the 20th century and are of two types: metalled (hard-surfaced) and unmetalled roads. Metalled roadways are made to sustain vehicular load and so are usually made on frequently used roads. Unmetalled roads, also known as gravel roads or dirt roads, are rough and can sustain less weight. Road surfaces are frequently marked to guide traffic.

Asphalt concrete is a composite material commonly used to surface roads, parking lots, airports, and the core of embankment dams. Asphalt mixtures have been used in pavement construction since the beginning of the twentieth century. It consists of mineral aggregate bound together with bitumen, laid in layers, and compacted.

Permeable paving surfaces are made of either a porous material that enables stormwater to flow through it or nonporous blocks spaced so that water can flow between the gaps. Permeable paving can also include a variety of surfacing techniques for roads, parking lots, and pedestrian walkways. Permeable pavement surfaces may be composed of; pervious concrete, porous asphalt, paving stones, or interlocking pavers. Unlike traditional impervious paving materials such as concrete and asphalt, permeable paving systems allow stormwater to percolate and infiltrate through the pavement and into the aggregate layers and/or soil below. In addition to reducing surface runoff, permeable paving systems can trap suspended solids, thereby filtering pollutants from stormwater.

A pothole is a pot-shaped depression in a road surface, usually asphalt pavement, where traffic has removed broken pieces of the pavement. It is usually the result of water in the underlying soil structure and traffic passing over the affected area. Water first weakens the underlying soil; traffic then fatigues and breaks the poorly supported asphalt surface in the affected area. Continued traffic action ejects both asphalt and the underlying soil material to create a hole in the pavement.

A paver is a paving stone, tile, brick or brick-like piece of concrete commonly used as exterior flooring. They are generally placed on top of a foundation which is made of layers of compacted stone and sand. The pavers are placed in the desired pattern and the space between pavers is then filled with a polymeric sand. No actual adhesive or retaining method is used other than the weight of the paver itself except edging. Pavers can be used to make roads, driveways, patios, walkways and other outdoor platforms.

Pierre-Marie-Jérôme Trésaguet was a French engineer. He is widely credited with establishing the first scientific approach to road building about the year 1764. Among his innovations was the use of a base layer of large stone covered with a thin layer of smaller stone. The advantage of this two-layer configuration was that when rammed or rolled by traffic the stones jammed into one another forming a strong wear resistant surface which offered less obstruction to traffic.

A curb, or kerb, is the edge where a raised sidewalk or road median/central reservation meets a street or other roadway.

Chipseal is a pavement surface treatment that combines one or more layers of asphalt with one or more layers of fine aggregate. In the United States, chipseals are typically used on rural roads carrying lower traffic volumes, and the process is often referred to as asphaltic surface treatment. This type of surface has a variety of other names including tar-seal or tarseal, tar and chip, sprayed sealsurface dressing, or simply seal.

Stone mastic asphalt (SMA), also called stone-matrix asphalt, was developed in Germany in the 1960s with the first SMA pavements being placed in 1968 near Kiel. It provides a deformation-resistant, durable surfacing material, suitable for heavily trafficked roads. SMA has found use in Europe, Australia, the United States, and Canada as a durable asphalt surfacing option for residential streets and highways. SMA has a high coarse aggregate content that interlocks to form a stone skeleton that resists permanent deformation. The stone skeleton is filled with a mastic of bitumen and filler to which fibres are added to provide adequate stability of bitumen and to prevent drainage of binder during transport and placement. Typical SMA composition consists of 70−80% coarse aggregate, 8−12% filler, 6.0−7.0% binder, and 0.3 per cent fibre.

The history of road transport started with the development of tracks by humans and their beasts of burden.

Road slipperiness is a condition of low skid resistance due to insufficient road friction. It is a result of snow, ice, water, loose material and the texture of the road surface on the traction produced by the wheels of a vehicle.

Court Avenue is a small street in downtown Bellefontaine, Ohio, United States, located adjacent to the Logan County Courthouse. First paved in 1893, it is known for being the first street in the United States to be paved with concrete.

R.S. Blome Granitoid Pavement is a historic road surface, as well as the associated cut sandstone curbs in a few sections, found in three of the oldest residential sections of Grand Forks, North Dakota. It is a Portland cement–aggregate combination that was intended to bridge the gap between the needs of Horse-drawn vehicles, which required sure footing, and automobiles, which needed a hard, resilient surface, in the earliest part of the 20th century.