The politics of the United Kingdom functions within a constitutional monarchy where executive power is delegated by legislation and social conventions to a unitary parliamentary democracy. From this a hereditary monarch, currently Charles III, serves as head of state while the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, currently Rishi Sunak, serves as the elected head of government.

The West Lothian question, also known as the English question, is a political issue in the United Kingdom. It concerns the question of whether MPs from Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales who sit in the House of Commons should be able to vote on matters that affect only England, while neither they nor MPs from England are able to vote on matters that have been devolved to the Northern Ireland Assembly, the Scottish Parliament and the Senedd. The term West Lothian question was coined by Enoch Powell MP in 1977 after Tam Dalyell, the Labour MP for the Scottish constituency of West Lothian, raised the matter repeatedly in House of Commons debates on devolution.

Scottish independence is the notion of Scotland as a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom, and refers to the political movement that is campaigning to bring it about.

A legislative consent motion is a motion passed by either the Scottish Parliament, Senedd, or Northern Ireland Assembly, in which it consents that the Parliament of the United Kingdom may pass legislation on a devolved issue over which the devolved government has regular legislative authority.

Politics of England forms the major part of the wider politics of the United Kingdom, with England being more populous than all the other countries of the United Kingdom put together. As England is also by far the largest in terms of area and GDP, its relationship to the UK is somewhat different from that of Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. The English capital London is also the capital of the UK, and English is the dominant language of the UK. Dicey and Morris (p26) list the separate states in the British Islands. "England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark.... is a separate country in the sense of the conflict of laws, though not one of them is a State known to public international law." But this may be varied by statute.

Referendums in the United Kingdom are occasionally held at a national, regional or local level. Historically, national referendums are rare due to the long-standing principle of parliamentary sovereignty. There is no constitutional requirement to hold a national referendum for any purpose or on any issue however the UK Parliament is free to legislate through an Act of Parliament for a referendum to be held on any question at any time, but unless it is strictly legislated for these cannot be constitutionally binding on either the Government or Parliament, although they usually have a persuasive political effect.

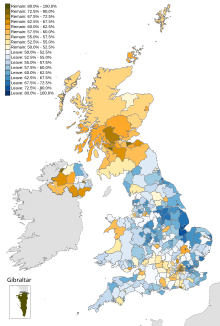

Unionism in Scotland is a political movement which favours the continuation of the political union between Scotland and the other countries of the United Kingdom, and hence is opposed to Scottish independence. Scotland is one of four countries of the United Kingdom which has its own devolved government and Scottish Parliament, as well as representation in the UK Parliament. There are many strands of political Unionism in Scotland, some of which have ties to Unionism and Loyalism in Northern Ireland. The two main political parties in the UK — the Conservatives support Scotland remaining part of the UK.

A devolved English parliament is a proposed institution that would give separate decision-making powers to representatives for voters in England, similar to the representation given by the Senedd, the Scottish Parliament and the Northern Ireland Assembly. A devolved English parliament is an issue in the politics of the United Kingdom.

Politics in Wales forms a distinctive polity in the wider politics of the United Kingdom, with Wales as one of the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom (UK).

English independence is a political stance advocating secession of England from the United Kingdom. Support for secession of England has been influenced by the increasing devolution of political powers to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, where independence from the United Kingdom is a prominent subject of political debate.

Welsh independence is the political movement advocating for Wales to become a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom.

Unionism in the United Kingdom, also referred to as UK unionism or British unionism, is a political stance favouring the continued unity of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland as one sovereign state, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Those who support the union are referred to as "Unionists". Though not all unionists are nationalists, UK or British unionism is associated with British nationalism, which asserts that the British are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of the Britons, which may include people of English, Scottish, Welsh, Irish, Cornish, Jersey, Manx and Guernsey descent.

Since 1922, the United Kingdom comprises three constituent countries: England, Scotland, and Wales, as well as Northern Ireland. The UK Prime Minister's website has used the phrase "countries within a country" to describe the United Kingdom. Some statistical summaries, such as those for the twelve NUTS 1 regions of the UK, refer to Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as "regions". With regard to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales particularly, the descriptive name one uses "can be controversial, with the choice often revealing one's political preferences".

Devolution is the process in which the central British parliament grants administrative powers to the devolved Scottish Parliament. Prior to the advent of devolution, some had argued for a Scottish Parliament within the United Kingdom – while others have since advocated for complete independence. The people of Scotland first got the opportunity to vote in a referendum on proposals for devolution in 1979 and, although a majority of those voting voted 'Yes', the referendum legislation also required 40% of the electorate to vote 'Yes' for the plans to be enacted and this was not achieved. A second referendum opportunity in 1997, this time on a strong proposal, resulted in an overwhelming 'Yes' victory, leading to the Scotland Act 1998 being passed and the Scottish Parliament being established in 1999.

In the United Kingdom, devolution is the Parliament of the United Kingdom's statutory granting of a greater level of self-government to the Scottish Parliament, the Senedd, the Northern Ireland Assembly and the London Assembly and to their associated executive bodies the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government, the Northern Ireland Executive and in England, the Greater London Authority and combined authorities.

Unionism in Wales is the political view that supports a political union between Wales and the other countries of the United Kingdom. As well as the current state of the UK, unionism may also include support for Federalism in the United Kingdom and a United Kingdom Confederation.

Federalism in the United Kingdom aims at constitutional reform to achieve a federal UK or a British federation, where there is a division of legislative powers between two or more levels of government, so that sovereignty is decentralised between a federal government and autonomous governments in a federal system.

The United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed in December 2020. It is concerned with trade within the UK, as the UK is no longer subject to EU law. The act seeks to prevent internal trade barriers among the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom, and to restrict the way that certain legislative powers of the devolved administrations can operate in practice. It introduces principles of mutual recognition and non-discrimination into UK trade law.

Welsh devolution is the transfer of legislative power for self-governance to Wales by the Government of the United Kingdom.

There have been various proposals for constitutional reform in the United Kingdom.