Apollo 13 was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the lunar landing was aborted after an oxygen tank in the service module (SM) ruptured two days into the mission, disabling its electrical and life-support system. The crew, supported by backup systems on the lunar module (LM), instead looped around the Moon in a circumlunar trajectory and returned safely to Earth on April 17. The mission was commanded by Jim Lovell, with Jack Swigert as command module (CM) pilot and Fred Haise as lunar module (LM) pilot. Swigert was a late replacement for Ken Mattingly, who was grounded after exposure to rubella.

Apollo 9 was the third human spaceflight in NASA's Apollo program. Flown in low Earth orbit, it was the second crewed Apollo mission that the United States launched via a Saturn V rocket, and was the first flight of the full Apollo spacecraft: the command and service module (CSM) with the Lunar Module (LM). The mission was flown to qualify the LM for lunar orbit operations in preparation for the first Moon landing by demonstrating its descent and ascent propulsion systems, showing that its crew could fly it independently, then rendezvous and dock with the CSM again, as would be required for the first crewed lunar landing. Other objectives of the flight included firing the LM descent engine to propel the spacecraft stack as a backup mode, and use of the portable life support system backpack outside the LM cabin.

Apollo 10 was the fourth human spaceflight in the United States' Apollo program and the second to orbit the Moon. NASA, the mission's operator, described it as a "dress rehearsal" for the first Moon landing. It was designated an "F" mission, intended to test all spacecraft components and procedures short of actual descent and landing.

Apollo 12 was the sixth crewed flight in the United States Apollo program and the second to land on the Moon. It was launched on November 14, 1969, by NASA from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida. Commander Charles "Pete" Conrad and Lunar Module Pilot Alan L. Bean performed just over one day and seven hours of lunar surface activity while Command Module Pilot Richard F. Gordon remained in lunar orbit.

Apollo 17 was the eleventh and final mission of NASA's Apollo program, the sixth and most recent time humans have set foot on the Moon or traveled beyond low Earth orbit. Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt walked on the Moon, while Command Module Pilot Ronald Evans orbited above. Schmitt was the only professional geologist to land on the Moon; he was selected in place of Joe Engle, as NASA had been under pressure to send a scientist to the Moon. The mission's heavy emphasis on science meant the inclusion of a number of new experiments, including a biological experiment containing five mice that was carried in the command module.

Skylab was the United States' first space station, launched by NASA, occupied for about 24 weeks between May 1973 and February 1974. It was operated by three trios of astronaut crews: Skylab 2, Skylab 3, and Skylab 4. Operations included an orbital workshop, a solar observatory, Earth observation and hundreds of experiments. Skylab's orbit eventually decayed and it disintegrated in the atmosphere on July 11, 1979, scattering debris across the Indian Ocean and Western Australia.

Alan LaVern Bean was an American naval officer and aviator, aeronautical engineer, test pilot, NASA astronaut and painter. He was selected to become an astronaut by NASA in 1963 as part of Astronaut Group 3, and was the fourth person to walk on the Moon.

STS-3 was NASA's third Space Shuttle mission, and was the third mission for the Space Shuttle Columbia. It launched on March 22, 1982, and landed eight days later on March 30, 1982. The mission, crewed by Jack R. Lousma and C. Gordon Fullerton, involved extensive orbital endurance testing of Columbia itself, as well as numerous scientific experiments. STS-3 was the first shuttle launch with an unpainted external tank, and the only mission to land at the White Sands Space Harbor near Alamogordo, New Mexico. The orbiter was forced to land at White Sands due to flooding at its originally planned landing site, Edwards Air Force Base.

Skylab 2 was the first crewed mission to Skylab, the first American orbital space station. The mission was launched on an Apollo command and service module by a Saturn IB rocket on May 25, 1973, and carried NASA astronauts Pete Conrad, Joseph P. Kerwin, Paul J. Weitz to the station. The name Skylab 2 also refers to the vehicle used for that mission. The Skylab 2 mission established a twenty-eight-day record for human spaceflight duration. Furthermore, its crew was the first space station occupants ever to return safely to Earth – the only previous space station occupants, the crew of the 1971 Soyuz 11 mission that had crewed the Salyut 1 station for twenty-four days, died upon reentry due to unexpected cabin depressurization.

Jack Robert Lousma is an American astronaut, aeronautical engineer, retired United States Marine Corps officer, former naval aviator, NASA astronaut, and politician. He was a member of the second crew, Skylab-3, on the Skylab space station in 1973. In 1982, he commanded STS-3, the third Space Shuttle mission. Lousma was inducted into the United States Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1997. He is the last living crew member of both of his spaceflights.

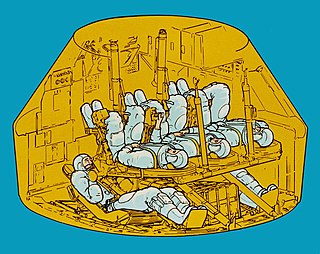

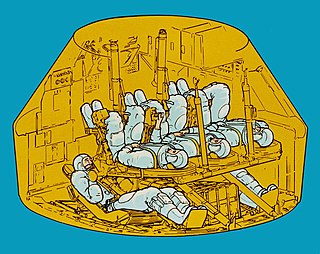

The Skylab Rescue Mission was an unflown rescue mission, planned as a contingency in the event of astronauts being stranded aboard the American Skylab space station. If flown, it would have used a modified Apollo Command Module that could be launched with a crew of two and return a crew of five.

Skylab 4 was the third crewed Skylab mission and placed the third and final crew aboard the first American space station.

The Apollo command and service module (CSM) was one of two principal components of the United States Apollo spacecraft, used for the Apollo program, which landed astronauts on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. The CSM functioned as a mother ship, which carried a crew of three astronauts and the second Apollo spacecraft, the Apollo Lunar Module, to lunar orbit, and brought the astronauts back to Earth. It consisted of two parts: the conical command module, a cabin that housed the crew and carried equipment needed for atmospheric reentry and splashdown; and the cylindrical service module which provided propulsion, electrical power and storage for various consumables required during a mission. An umbilical connection transferred power and consumables between the two modules. Just before reentry of the command module on the return home, the umbilical connection was severed and the service module was cast off and allowed to burn up in the atmosphere.

Several planned missions of the Apollo crewed Moon landing program of the 1960s and 1970s were canceled, for reasons which included changes in technical direction, the Apollo 1 fire, hardware delays, and budget limitations. After the landing by Apollo 12, Apollo 20, which would have been the final crewed mission to the Moon, was canceled to allow Skylab to launch as a "dry workshop". The next two missions, Apollos 18 and 19, were later canceled after the Apollo 13 incident and further budget cuts. Two Skylab missions also ended up being canceled. Two complete Saturn V rockets remained unused and were put on display in the United States.

NASA Astronaut Group 4 was a group of six astronauts selected by NASA in June 1965. While the astronauts of the first two groups were required to have an undergraduate degree or the professional equivalent in engineering or the sciences, they were chosen for their experience as test pilots. Test pilot experience was waived as a requirement for the third group, and military jet fighter aircraft experience could be substituted. Group 4 was the first chosen on the basis of research and academic experience, with NASA providing pilot training as necessary. Initial screening of applicants was conducted by the National Academy of Sciences.

NASA Astronaut Group 5 was a group of nineteen astronauts selected by NASA in April 1966. Of the six Lunar Module Pilots that walked on the Moon, three came from Group 5. The group as a whole is roughly split between the half who flew to the Moon, and the half who flew Skylab and Space Shuttle, providing the core of Shuttle commanders early in that program. This group is also distinctive in being the only time when NASA hired a person into the astronaut corps who had already earned astronaut wings, X-15 pilot Joe Engle. John Young labeled the group the Original Nineteen in parody of the original Mercury Seven astronauts.

Manned Venus Flyby was a 1967–1968 NASA proposal to send three astronauts on a flyby mission to Venus in an Apollo-derived spacecraft in 1973–1974, using a gravity assist to shorten the return journey to Earth.

The Apollo Telescope Mount, or ATM, was a crewed solar observatory that was a part of Skylab, the first American space station. It could observe the Sun in wavelengths ranging from soft X-rays, ultra-violet, and visible light.