The Boy Who Cried Wolf is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 210 in the Perry Index. From it is derived the English idiom "to cry wolf", defined as "to give a false alarm" in Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable and glossed by the Oxford English Dictionary as meaning to make false claims, with the result that subsequent true claims are disbelieved.

The Farmer and the Stork is one of Aesop's fables which appears in Greek in the collections of both Babrius and Aphthonius and has differed little in the telling over the centuries. The story relates how a farmer plants traps in his field to catch the cranes and geese that are stealing the seeds he has sown. When he checks the traps, he finds among the other birds a stork, who pleads to be spared because it is harmless and has taken no part in the theft. The farmer replies that since it has been caught in the company of thieves, it must suffer the same fate. The moral of the story, which is announced beforehand in the oldest texts, is that associating with bad companions will lead to bad consequences.

The Walnut Tree is one of Aesop's fables and numbered 250 in the Perry Index. It later served as a base for a misogynistic proverb, which encourages the violence against walnut trees, asses and women.

The Hawk and the Nightingale is one of the earliest fables recorded in Greek and there have been many variations on the story since Classical times. The original version is numbered 4 in the Perry Index and the later Aesop version, sometimes going under the title "The Hawk, the Nightingale and the Birdcatcher", is numbered 567. The stories began as a reflection on the arbitrary use of power and eventually shifted to being a lesson in the wise use of resources.

The Fox and the Lion is one of Aesop's Fables and represents a comedy of manners. It is number 10 in the Perry Index.

The Gourd and the Palm-tree is a rare fable of West Asian origin that was first recorded in Europe in the Middle Ages. In the Renaissance a variant appeared in which a pine took the palm-tree's place and the story was occasionally counted as one of Aesop's Fables..

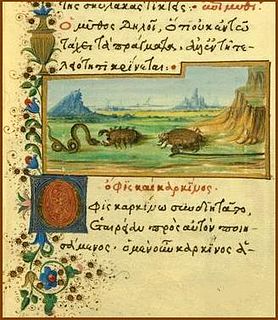

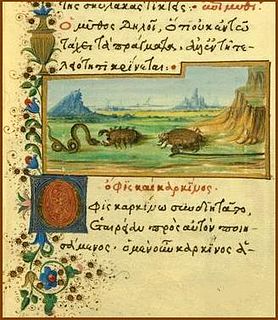

Speaking of The Snake and the Crab in Ancient Greece was the equivalent of the modern idiom, 'Pot calling the kettle black'. A fable attributed to Aesop was eventually created about the two creatures and later still yet another fable concerning a crab and its offspring was developed to make the same point.

The Crow or Raven and the Snake or Serpent is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 128 in the Perry Index. Alternative Greek versions exist and two of these were adopted during the European Renaissance. The fable is not to be confused with the story of this title in the Panchatantra, which is completely different.

The Bird-catcher or Fowler and the Blackbird was one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 193 in the Perry Index. In Greek sources, it featured a lark, but French and English versions have always named the blackbird as the bird involved.

The Elm and the Vine were associated particularly by Latin authors. Because pruned elm trees acted as vine supports, this was taken as a symbol of marriage and imagery connected with their pairing also became common in Renaissance literature. Various fables were created out of their association in both Classical and later times. Although Aesop was not credited with these formerly, later fables hint at his authorship.

"The Astrologer who Fell into a Well" is a fable based on a Greek anecdote concerning the pre-Socratic philosopher Thales of Miletus. It was one of several ancient jokes that were absorbed into Aesop's Fables and is now numbered 40 in the Perry Index. During the scientific attack on astrology in the 16th–17th centuries, the story again became very popular.

The cautionary tale of The Mouse and the Oyster is rarely mentioned in Classical literature but is counted as one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 454 in the Perry Index. It has been variously interpreted, either as a warning against gluttony or as a caution against unwary behaviour.

Developed by authors during Renaissance times, the story of an ass eating thistles was a late addition to collections of Aesop's Fables. Beginning as a condemnation of miserly behaviour, it eventually was taken to demonstrate how preferences differ.

The Dove and the Ant is a story about the reward of compassionate behaviour. Included among Aesop's Fables, it is numbered 235 in the Perry Index.

The Ass Carrying an Image is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 182 in the Perry Index. It is directed against human conceit but at one period was also used to illustrate the argument in Canon Law that the sacramental act is not diminished by the priest's unworthiness.

The Frog and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables and exists in several versions. It is numbered 384 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern versions of uncertain origin which are classified as Aarne-Thompson type 278, concerning unnatural relationships. The stories make the point that the treacherous are destroyed by their own actions.

The Ape and the Fox is a fable credited to Aesop and is numbered 81 in the Perry Index. However, the story goes back before Aesop’s time and an alternative variant may even be of Asian origin.

The Farmer and his Sons is a story of Greek origin that is included among Aesop's Fables and is listed as 42 in the Perry Index. It illustrates both the value of hard work and the need to temper parental advice with practicality.

The lion grown old is counted among Aesop’s Fables and is numbered 481 in the Perry Index. It is used in illustration of the insults given those who have fallen from power and has a similar moral to the fable of The dogs and the lion's skin. Parallel proverbs of similar meaning were later associated with it.

The Kite and the Doves is a political fable ascribed to Aesop that is numbered 486 in the Perry Index. During the Middle Ages the fable was modified by the introduction of a hawk as an additional character, followed by a change in the moral drawn from it.

![Heinrich Wirrich [de]'s broadside satire on human folly showing a fowler, 1588 Ich Lavff Geschwind Mit Der Leimstangen.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/Ich_Lavff_Geschwind_Mit_Der_Leimstangen.jpg/270px-Ich_Lavff_Geschwind_Mit_Der_Leimstangen.jpg)