European versions

It was the Adagia (1508), the proverb collection of Erasmus, that brought the fables to the notice of Renaissance Europe. He recorded the Greek proverb Κόραξ τὸν ὄφιν (translated as corvus serpentem [rapuit]), commenting that it came from Aesop's fable, as well as citing the Greek poem in which it figures and giving a translation. [5] He also compared the proverb with Κορώνη τὸν σκορπίον (Cornix scorpium), noticed earlier in his collection. [6]

The latter fable of the Raven and the Scorpion recommended itself as a moral device to the compilers of Emblem books. The earliest of these was Andrea Alciato, whose influential Emblemata was published in many formats and in several countries from 1531 onwards. [7] There it figures as Emblem 173 and is accompanied by a poem in Latin. The device's title is Iusta ultio, which may be translated as 'just revenge' or what is now understood by the English phrase 'poetic justice'. This was further emphasised in the French translation of 1536, where the French proverb Les preneurs sont prins (the hunters are caught in their own wiles) is punned upon in an accompanying poem by Jean Lefevre. [8] There were also German translations from 1536 onwards. [9] The 1615 Spanish edition with commentary, Declaracion magistral sobre las Emblemas de Andres Alciato, references the Adagia and gives Erasmus' Latin translation of the poem by Archias; [10] the even fuller Italian edition of 1621 quotes the Greek as well. [11]

The emblem was illustrated independently by Marcus Gheeraerts in the Bruges edition of Warachtige Fabulen de Dieren (1567) with verses in Flemish by Edewaerd de Dene signifying that God will avenge his people. A French translation was published as Esbatement Moral (1578) and in German by Aegidius Sadeler as Theatrum Morum (1608). The last of these was retranslated into French by Trichet du Fresne, of which there were editions in 1659, 1689 and 1743. [12]

Meanwhile, it was the fable of the Crow and the Snake that had been chosen by Gabriele Faerno for his collection of a hundred fables in Neo-Latin verse, with the conclusion that often our gains turn into occasions for regret. [13] In the following decade, the French poet Jean Antoine de Baïf used it for the witty, verbally concentrated version in his Mimes, enseignemens et proverbes (1576):

- Crow found the snake asleep

- And, wanting her to eat,

- With his beak bit her awake:

- Waking up bitten,

- She gave the bite back,

- Her caress kissed him off. (I.432–438) [14]

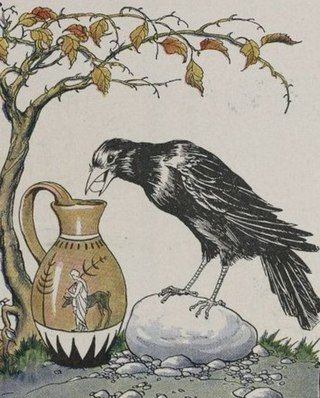

In England this version of the story first appeared in Roger L'Estrange's collection of Aesop's fables (1692), where he advised readers not to meddle with the unfamiliar. [15] For Samuel Croxall the story served as a warning against covetousness [16] and for Thomas Bewick it illustrated the danger of being ruled by brute appetite. [17] The latter interpretation had earlier been preferred by Guillaume La Perrière in his emblem book Le theatre des bons engins (1544). There the greedy crow is poisoned internally after swallowing the snake, "thinking it tasted good as sugar or venison". [18]