A miser is a person who is reluctant to spend money, sometimes to the point of forgoing even basic comforts and some necessities, in order to hoard money or other possessions. Although the word is sometimes used loosely to characterise anyone who is mean with their money, if such behaviour is not accompanied by taking delight in what is saved, it is not properly miserly.

The story and metaphor of The Dog in the Manger derives from an old Greek fable which has been transmitted in several different versions. Interpreted variously over the centuries, the metaphor is now used to speak of one who spitefully prevents others from having something for which one has no use. Although the story was ascribed to Aesop's Fables in the 15th century, there is no ancient source that does so.

The Miser and his Gold is one of Aesop's Fables that deals directly with human weaknesses, in this case the wrong use of possessions. Since this is a story dealing only with humans, it allows the point to be made directly through the medium of speech rather than be surmised from the situation. It is numbered 225 in the Perry Index.

The Monkey and the Cat is best known as a fable adapted by Jean de La Fontaine under the title Le Singe et le Chat that appeared in the second collection of his Fables in 1679 (IX.17). It is the source of popular idioms in both English and French, with the general meaning of being the dupe of another.

The Dog and Its Reflection is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 133 in the Perry Index. The Greek language original was retold in Latin and in this way was spread across Europe, teaching the lesson to be contented with what one has and not to relinquish substance for shadow. There also exist Indian variants of the story. The morals at the end of the fable have provided both English and French with proverbs and the story has been applied to a variety of social situations.

The Walnut Tree is one of Aesop's fables and numbered 250 in the Perry Index. It later served as a base for a misogynistic proverb, which encourages the violence against walnut trees, asses and women.

The Two Pots is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 378 in the Perry Index. The fable may stem from proverbial sources.

The Fox and the Lion is one of Aesop's Fables and represents a comedy of manners. It is number 10 in the Perry Index.

The Crow or Raven and the Snake or Serpent is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 128 in the Perry Index. Alternative Greek versions exist and two of these were adopted during the European Renaissance. The fable is not to be confused with the story of this title in the Panchatantra, which is completely different.

"The Astrologer who Fell into a Well" is a fable based on a Greek anecdote concerning the pre-Socratic philosopher Thales of Miletus. It was one of several ancient jokes that were absorbed into Aesop's Fables and is now numbered 40 in the Perry Index. During the scientific attack on astrology in the 16th–17th centuries, the story again became very popular.

The cautionary tale of The Mouse and the Oyster is rarely mentioned in Classical literature but is counted as one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 454 in the Perry Index. It has been variously interpreted, either as a warning against gluttony or as a caution against unwary behaviour.

The Fowler and the Snake is a story of Greek origin that demonstrates the fate of predators. It was counted as one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 115 in the Perry Index.

The Fox and the Mask is one of Aesop's Fables, of which there are both Greek and Latin variants. It is numbered 27 in the Perry Index.

The Ass Carrying an Image is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 182 in the Perry Index. It is directed against human conceit but at one period was also used to illustrate the argument in Canon Law that the sacramental act is not diminished by the priest's unworthiness.

The Frog and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables and exists in several versions. It is numbered 384 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern versions of uncertain origin which are classified as Aarne-Thompson type 278, concerning unnatural relationships. The stories make the point that the treacherous are destroyed by their own actions.

Hercules and the Wagoner or Hercules and the Carter is a fable credited to Aesop. It is associated with the proverb "God helps those who help themselves", variations on which are found in other ancient Greek authors.

In ancient times, the beaver was hunted for its testicles, which it was thought had medicinal qualities. The story that the animal would gnaw these off to save itself when hunted was preserved by some ancient Greek naturalists and perpetuated into the Middle Ages. It also appeared as a Greek fable ascribed to Aesop and is numbered 118 in the Perry Index.

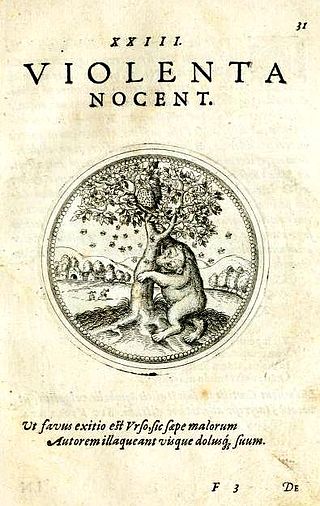

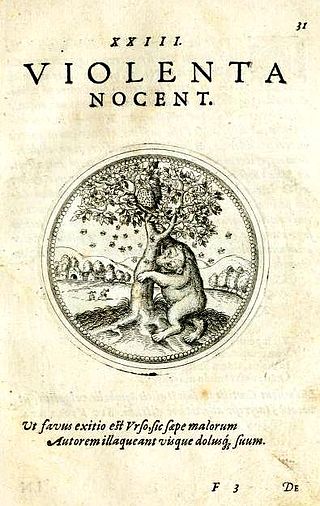

The Bear and the Bees is a fable of North Italian origin that became popular in other countries between the 16th - 19th centuries. There it has often been ascribed to Aesop's fables, although there is no evidence for this and it does not appear in the Perry Index. Various versions have been given different interpretations over time and artistic representations have been common.

"The Lion Grown Old" is counted among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 481 in the Perry Index. It is used in illustration of the insults given those who have fallen from power and has a similar moral to the fable of The dogs and the lion's skin. Parallel proverbs of similar meaning were later associated with it.

The Oxen and the Creaking Cart is a situational fable ascribed to Aesop and is numbered 45 in the Perry Index. Originally directed against complainers, it was later linked with the proverb 'the worst wheel always creaks most' and aimed emblematically at babblers of all sorts.