The Ass and his Masters is a fable that has also gone by the alternative titles The ass and the gardener and Jupiter and the ass. Included among Aesop's Fables, it is numbered 179 in the Perry Index. [1]

The Ass and his Masters is a fable that has also gone by the alternative titles The ass and the gardener and Jupiter and the ass. Included among Aesop's Fables, it is numbered 179 in the Perry Index. [1]

The fable only appears in Greek sources in classical times. In it, an ass in the employ of a gardener complains to the king of the gods that he is not fed adequately and asks for a change of master. He is transferred to a potter and prays for another change because the loads are so heavy. Now he passes to a tanner and regrets leaving his first employer. At a time when slavery was common, the fable was applied to the dissatisfaction felt by slaves. [2]

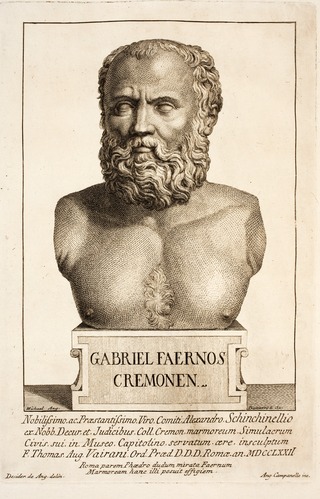

In Renaissance times two Neo-Latin poets contributed to making the story better known. Gabriele Faerno as Asinus dominus mutans, with the moral that a change of master only brings worse; [3] and Hieronymus Osius as Asinus et olitor (The ass and the gardener, the title by which it was known in Greece), [4] with the comment that habitual dissatisfaction always brings a desire for change. [5] Jean de la Fontaine also added the story to his Fables as L'ane et ses maitres (The ass and his masters, VI.11) with the even harsher comment that providence has better things to do than listen to those who are never satisfied. [6]

In Britain the fable was generally known under the title "The ass and Jupiter" and appears as such in the verse paraphrase of John Ogilby; [7] in the prose collections of Samuel Croxall [8] and Thomas Bewick; [9] and the poetical version of Brooke Boothby. [10] The Dutch painter Dirck Stoop also made an etching of the fable under that title in 1655. [11]

Laurentius Abstemius told a different version of the fable in his Hecatomythium (1490). In this the ass, tired of cold and only straw to eat, pines for the end of winter. In spring there is so much work that he wishes for summer, and then for autumn, under the burdens each season brings him, and in the end 'his last Prayer is for Winter again; and that he may but take up his Rest where he began his Complaint'. [12]

Phaedrus, who was a freed slave, did not record the fable about the discontented ass, but a similar moral appears at the end of his version of The Frogs Who Desired a King. The citizens of Athens are grumbling at their new ruler and Aesop advises them, after he has told the fable, 'hoc sustinete, maius ne veniat, malum (hang on to your present evil, lest it become worse). [13]

Some quite different stories exist with much the same moral as this, retaining certain aspects of the story-line of "The Ass and his Masters". These include a succession of three changes, each worse than before, followed by prayer for the preservation of the last.

An early Tudor jest book records a later Classical anecdote. In this an old lady prays for the continued well-being of the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse. On being asked by him why, she replies, [14]

Whan I was a mayde, we had a tyran raignynge ouer us, whose death I greatly desyred; whan he was slayne, there succided an other yet more cruell than he, out of whose gouernance to be also deliuered I thought it a hygh benifyte. The thyrde is thy selfe, that haste begon to raygne ouer vs more importunately than either of the other two. Thus, fearynge leest, whan thou arte gone, a worse shuld succede and reigne ouer vs, I praye God dayly to preserue the in helthe.

The story had earlier appeared in Thomas Aquinas' De Regimine Principum, in the context of a discussion of the drawbacks of resisting tyranny. [15]

Slightly earlier in the Middle Ages, Odo of Cheriton had drawn a similar lesson from a monastic situation. His light-hearted story concerns monks who pray for the death of their abbot. The first had given them three courses at a meal but not enough to satisfy their hunger; after his death he is succeeded by an abbot who allows them only two courses, and then on his death by one who allows only a single course. One of the monks then prays for the long life of this abbot for fear that they might starve altogether under a successor. [16]

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of diverse origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The Frog and the Ox appears among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 376 in the Perry Index. The story concerns a frog that tries to inflate itself to the size of an ox, but bursts in the attempt. It has usually been applied to socio-economic relations.

The Frogs Who Desired a King is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 44 in the Perry Index. Throughout its history, the story has been given a political application.

The Ass in the Lion's Skin is one of Aesop's Fables, of which there are two distinct versions. There are also several Eastern variants, and the story's interpretation varies accordingly.

The Ass and the Pig is one of Aesop's Fables that was never adopted in the West but has Eastern variants that remain popular. Their general teaching is that the easy life and seeming good fortune of others conceal a threat to their welfare.

The humanist scholar Gabriele Faerno, also known by his Latin name of Faernus Cremonensis, was born in Cremona about 1510 and died in Rome on 17 November 1561. He was a scrupulous textual editor and an elegant Latin poet who is best known now for his collection of Aesop's Fables in Latin verse.

The Fox and the Lion is one of Aesop's Fables and represents a comedy of manners. It is number 10 in the Perry Index.

The Horse and the Donkey is one of a number of ancient animal fables that illustrate the importance of helping others and the consequences of neglecting that duty.

The Dog and the Wolf is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 346 in the Perry Index. It has been popular since antiquity as an object lesson of how freedom should not be exchanged for comfort or financial gain. An alternative fable with the same moral concerning different animals is less well known.

The Man with Two Mistresses is one of Aesop's Fables that deals directly with human foibles. It is numbered 31 in the Perry Index.

The Ass Carrying an Image is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 182 in the Perry Index. It is directed against human conceit but at one period was also used to illustrate the argument in Canon Law that the sacramental act is not diminished by the priest's unworthiness.

Hercules and the Wagoner or Hercules and the Carter is a fable credited to Aesop. It is associated with the proverb "God helps those who help themselves", variations on which are found in other ancient Greek authors.

The Old Man and the Ass began as a fable with a political theme. Appearing among Aesop's Fables, it is numbered 476 in the Perry Index.

The Old Woman and the Wine Jar is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 493 in the Perry Index. It has been applied to situations where an influence for good is lasting, such as the effect of education.

There are no less than six fables concerning an impertinent insect, which is taken in general to refer to the kind of interfering person who makes himself out falsely to share in the enterprise of others or to be of greater importance than he is in reality. Some of these stories are included among Aesop's Fables, while others are of later origin, and from them have been derived idioms in several languages.

The Eagle and the Fox is a fable of friendship betrayed and avenged. Counted as one of Aesop’s Fables, it is numbered 1 in the Perry Index. The central situation concerns an eagle that seizes a fox’s cubs and bears them off to feed its young. There are then alternative endings to the story, in one of which the fox exacts restitution, while in the other it gains retribution for its injury.

"The Lion Grown Old" is counted among Aesop’s Fables and is numbered 481 in the Perry Index. It is used in illustration of the insults given those who have fallen from power and has a similar moral to the fable of The dogs and the lion's skin. Parallel proverbs of similar meaning were later associated with it.

The Kite and the Doves is a political fable ascribed to Aesop that is numbered 486 in the Perry Index. During the Middle Ages the fable was modified by the introduction of a hawk as an additional character, followed by a change in the moral drawn from it.

The fable of how the horse lost its liberty in the course of settling a petty conflict exists in two versions involving either a stag or a boar and is numbered 269 in the Perry Index. When the story is told in a political context, it warns against seeking a remedy that leaves one worse off than before. Where economic circumstances are involved, it teaches that independence is always better than compromised plenty.

The story of the bald man and the fly is found in the earliest collection of Aesop’s Fables and is numbered 525 in the Perry Index. Although it deals with the theme of just punishment, some later interpreters have used it as a counsel of restraint.