A jackass in office

The Greek fable tells of an ass that is carrying a religious image and takes the homage of the crowd as being paid to him personally. When pride makes it refuse to go further, the driver beats it and declares that the world has not yet become so backward that men bow down to asses. The Latin title of the fable, Asinus portans mysteria (or its Greek equivalent, ονος αγων μυστήρια), was used proverbially of such human conceit and was recorded as such in the Adagia of Erasmus. [2]

The fable was revived in Renaissance times by Andrea Alciato in his Emblemata under the heading Non tibi sed religioni (not for your sake but religion's), and is placed in the context of the Egyptian cult of Isis. [3] No less than three English versions of Alciato's accompanying Latin poem were written in the next few decades. The most significant is that of Geoffrey Whitney in his Choice of Emblemes, which is more a paraphrase dwelling foremost on the meaning of the fable. It draws the human parallel with religious 'pastors', but also with ambassadors in the secular sphere, both of whom act as intermediaries of a higher power. [4]

None of these authors ascribed the fable to Aesop, but Christoph Murer mentioned "Aesop's Ass" in his book of emblems, XL emblemata miscella nova (1620), where it was likened to those who pursue ambition. [5] At this time also the Neo-Latin poet Pantaleon Candidus alluded to it in describing "those who aspire to great honours". [6] A contemporary English reference in The Conversations at Little Gidding (about 1630) also mentions ‘Aesops Asse interpreting the Prostrate Worship of the People that was offered to the Golden Image on his back as intended to his Beastliness’. [7] This, however, was in the context of making a distinction between a man and his religious office. George Herbert (who may have taken part in these conversations) again alluded to this matter in his poem “The Church Porch” (lines 265-8)

- When baseness is exalted, do not bate

- The place its honour for the person’s sake.

- The shrine is that which thou doest venerate,

- And not the beast that bears it on his back. [8]

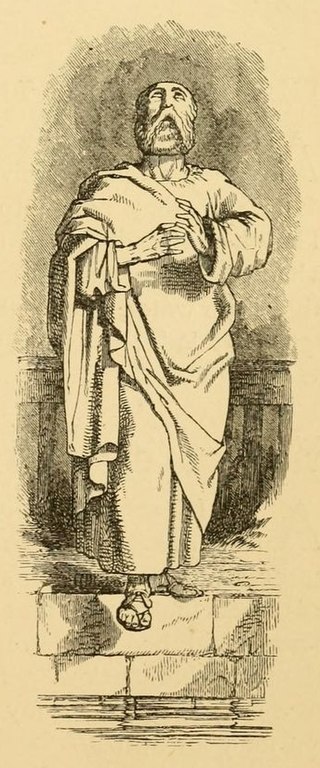

The story had another retelling in a Neo-Latin poem by Gabriele Faerno which, in its single-lined moral, draws the parallel with a magistrate who is only honoured for his office. [9] The story was eventually given a Catholic context in La Fontaine's Fables, where it was titled "The ass carrying relics". However, the ending limits the lesson to secular office, as does Faerno: 'As with a stupid magistrate, it's to the robe that you prostrate' (D’un magistrat ignorant/C’est la Robe qu’on salue). [10] Since then, illustrators of his Fables have often combined the fable and its lesson in the same picture, or even confined themselves to its worldly lesson alone.

Roger L'Estrange had similarly taken the fable, at much the same time as La Fontaine, as ‘a reproof to those men who take the honour and respect that is done to the character they sustain, to be paid to the person’. [11] But after his time, although there were subsequent inclusions in English fable collections, it appeared in none of the best known until Victorian times. The lesson was emphasised then by its being titled "The Jackass in Office", [12] in reference to the proverbial expression for a puffed up petty official, a jack in office.