Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The Miser and his Gold is one of Aesop's Fables that deals directly with human weaknesses, in this case the wrong use of possessions. Since this is a story dealing only with humans, it allows the point to be made directly through the medium of speech rather than be surmised from the situation. It is numbered 225 in the Perry Index.

The Dog and Its Reflection is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 133 in the Perry Index. The Greek language original was retold in Latin and in this way was spread across Europe, teaching the lesson to be contented with what one has and not to relinquish substance for shadow. There also exist Indian variants of the story. The morals at the end of the fable have provided both English and French with proverbs and the story has been applied to a variety of social situations.

The Oak and the Reed is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 70 in the Perry Index. It appears in many versions: in some it is with many reeds that the oak converses and in a late rewritten version it disputes with a willow.

The drowned woman and her husband is a story found in Mediaeval jest-books that entered the fable tradition in the 16th century. It was occasionally included in collections of Aesop's Fables but never became established as such and has no number in the Perry Index. Folk variants in which a contrary wife is sought upstream by her husband after she drowns are catalogued under the Aarne-Thompson classification system as type 1365A.

The Two Pots is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 378 in the Perry Index. The fable may stem from proverbial sources.

The Fox and the Lion is one of Aesop's Fables and represents a comedy of manners. It is number 10 in the Perry Index.

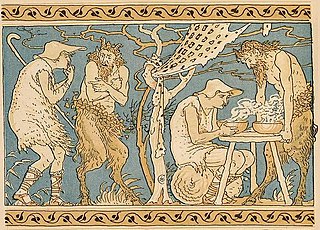

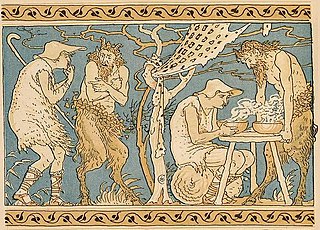

The Satyr and the Traveller is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 35 in the Perry Index. The popular idiom 'to blow hot and cold' is associated with it and the fable is read as a warning against duplicity.

The title of Shakespeare's Jest Book has been given to two quite different early Tudor period collections of humorous anecdotes, published within a few years of each other. The first was The Hundred Merry Tales, the only surviving complete edition of which was published in 1526. The other, published about 1530, was titled Merry Tales and Quick Answers and originally contained 113 stories. An augmented edition of 1564 contained 140.

The Crow or Raven and the Snake or Serpent is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 128 in the Perry Index. Alternative Greek versions exist and two of these were adopted during the European Renaissance. The fable is not to be confused with the story of this title in the Panchatantra, which is completely different.

"The Blind Man and the Lame" is a fable that recounts how two individuals collaborate in an effort to overcome their respective disabilities. The theme is first attested in Greek about the first century BCE. Stories with this feature occur in Asia, Europe and North America.

The Elm and the Vine were associated particularly by Latin authors. Because pruned elm trees acted as vine supports, this was taken as a symbol of marriage and imagery connected with their pairing also became common in Renaissance literature. Various fables were created out of their association in both Classical and later times. Although Aesop was not credited with these formerly, later fables hint at his authorship.

The Ass and his Masters is a fable that has also gone by the alternative titles The ass and the gardener and Jupiter and the ass. Included among Aesop's Fables, it is numbered 179 in the Perry Index.

The cautionary tale of The Mouse and the Oyster is rarely mentioned in Classical literature but is counted as one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 454 in the Perry Index. It has been variously interpreted, either as a warning against gluttony or as a caution against unwary behaviour.

Developed by authors during Renaissance times, the story of an ass eating thistles was a late addition to collections of Aesop's Fables. Beginning as a condemnation of miserly behaviour, it eventually was taken to demonstrate how preferences differ.

The Fowler and the Snake is a story of Greek origin that demonstrates the fate of predators. It was counted as one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 115 in the Perry Index.

The Fox and the Mask is one of Aesop's Fables, of which there are both Greek and Latin variants. It is numbered 27 in the Perry Index.

The Ass Carrying an Image is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 182 in the Perry Index. It is directed against human conceit but at one period was also used to illustrate the argument in Canon Law that the sacramental act is not diminished by the priest's unworthiness.

Hercules and the Wagoner or Hercules and the Carter is a fable credited to Aesop. It is associated with the proverb "God helps those who help themselves", variations on which are found in other ancient Greek authors.

The story of the feud between the eagle and the beetle is one of Aesop's Fables and often referred to in Classical times. It is numbered 3 in the Perry Index and the episode became proverbial. Although different in detail, it can be compared to the fable of The Eagle and the Fox. In both cases the eagle believes itself safe from retribution for an act of violence and is punished by the destruction of its young.