Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The Cat and the Mice is a fable attributed to Aesop of which there are several variants. Sometimes a weasel is the predator; the prey can also be rats and chickens.

Zeus and the Tortoise appears among Aesop's Fables and explains how the tortoise got her shell. It is numbered 106 in the Perry Index. From it derives the proverbial sentiment that 'There's no place like home'.

The phrase out of the frying pan into the fire is used to describe the situation of moving or getting from a bad or difficult situation to a worse one, often as the result of trying to escape from the bad or difficult one. It was the subject of a 15th-century fable that eventually entered the Aesopic canon.

The Walnut Tree is one of Aesop's fables and numbered 250 in the Perry Index. It later served as a base for a misogynistic proverb, which encourages the violence against walnut trees, asses and women.

The Fox and the Lion is one of Aesop's Fables and represents a comedy of manners. It is number 10 in the Perry Index.

Speaking of The Snake and the Crab in Ancient Greece was the equivalent of the modern idiom, 'Pot calling the kettle black'. A fable attributed to Aesop was eventually created about the two creatures and later still yet another fable concerning a crab and its offspring was developed to make the same point.

The Crow or Raven and the Snake or Serpent is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 128 in the Perry Index. Alternative Greek versions exist and two of these were adopted during the European Renaissance. The fable is not to be confused with the story of this title in the Panchatantra, which is completely different.

The Travellers and the Plane Tree is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 175 in the Perry Index. It may be compared with The Walnut Tree as having for theme ingratitude for benefits received. In this story two travellers rest from the sun under a plane tree. One of them describes it as useless and the tree protests at this view when they are manifestly benefiting from its shade.

The Fox and the Woodman is a cautionary story against hypocrisy included among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 22 in the Perry Index. Although the same basic plot recurs, different versions have included a variety of participants.

The Ass and his Masters is a fable that has also gone by the alternative titles The ass and the gardener and Jupiter and the ass. Included among Aesop's Fables, it is numbered 179 in the Perry Index.

The Heron and the Fish is a situational fable constructed to illustrate the moral that one should not be over-fastidious in making choices since, as the ancient proverb proposes, 'He that will not when he may, when he will he shall have nay'. Of ancient but uncertain origin, it gained popularity after appearing among La Fontaine's Fables.

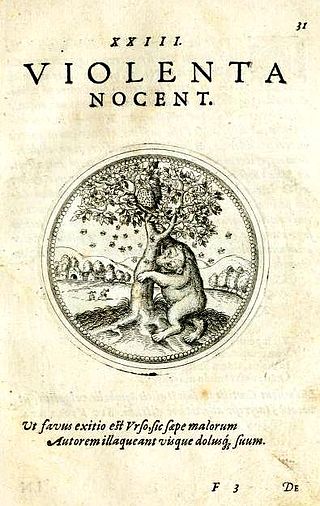

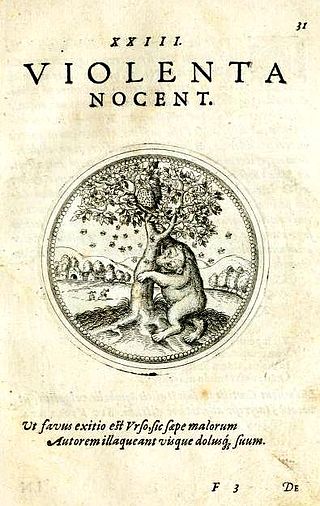

The Bear and the Bees is a fable of North Italian origin that became popular in other countries between the 16th - 19th centuries. There it has often been ascribed to Aesop's fables, although there is no evidence for this and it does not appear in the Perry Index. Various versions have been given different interpretations over time and artistic representations have been common.

There are no less than six fables concerning an impertinent insect, which is taken in general to refer to the kind of interfering person who makes himself out falsely to share in the enterprise of others or to be of greater importance than he is in reality. Some of these stories are included among Aesop's Fables, while others are of later origin, and from them have been derived idioms in several languages.

The classical legend that the swan sings at death was incorporated into one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 399 in the Perry Index. The fable also introduces the proverbial antithesis between the swan and the goose that gave rise to such sayings as ‘Every man thinks his own geese are swans’, in reference to blind partiality, and 'All his swans are turned to geese', referring to a reverse of fortune.

The story of the feud between the eagle and the beetle is one of Aesop's Fables and often referred to in Classical times. It is numbered 3 in the Perry Index and the episode became proverbial. Although different in detail, it can be compared to the fable of The Eagle and the Fox. In both cases the eagle believes itself safe from retribution for an act of violence and is punished by the destruction of its young.

"The Lion Grown Old" is counted among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 481 in the Perry Index. It is used in illustration of the insults given those who have fallen from power and has a similar moral to the fable of The dogs and the lion's skin. Parallel proverbs of similar meaning were later associated with it.

The Oxen and the Creaking Cart is a situational fable ascribed to Aesop and is numbered 45 in the Perry Index. Originally directed against complainers, it was later linked with the proverb 'the worst wheel always creaks most' and aimed emblematically at babblers of all sorts.

The fable of how the horse lost its liberty in the course of settling a petty conflict exists in two versions involving either a stag or a boar and is numbered 269 in the Perry Index. When the story is told in a political context, it warns against seeking a remedy that leaves one worse off than before. Where economic circumstances are involved, it teaches that independence is always better than compromised plenty.

The tale of the crab and the fox is of Greek origin and is counted as one of Aesop's fables; it is numbered 116 in the Perry Index. The moral is that one comes to grief through not sticking to one's allotted role in life