Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

A miser is a person who is reluctant to spend money, sometimes to the point of forgoing even basic comforts and some necessities, in order to hoard money or other possessions. Although the word is sometimes used loosely to characterise anyone who is mean with their money, if such behaviour is not accompanied by taking delight in what is saved, it is not properly miserly.

The Fox and the Grapes is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 15 in the Perry Index. The narration is concise and subsequent retellings have often been equally so. The story concerns a fox that tries to eat grapes from a vine but cannot reach them. Rather than admit defeat, he states they are undesirable. The expression "sour grapes" originated from this fable.

The Frog and the Ox appears among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 376 in the Perry Index. The story concerns a frog that tries to inflate itself to the size of an ox, but bursts in the attempt. It has usually been applied to socio-economic relations.

The Ant and the Grasshopper, alternatively titled The Grasshopper and the Ant, is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 373 in the Perry Index. The fable describes how a hungry grasshopper begs for food from an ant when winter comes and is refused. The situation sums up moral lessons about the virtues of hard work and planning for the future.

The lion's share is an idiomatic expression which now refers to the major share of something. The phrase derives from the plot of a number of fables ascribed to Aesop and is used here as their generic title. There are two main types of story, which exist in several different versions. Other fables exist in the East that feature division of prey in such a way that the divider gains the greater part - or even the whole. In English the phrase used in the sense of nearly all only appeared at the end of the 18th century; the French equivalent, le partage du lion, is recorded from the start of that century, following La Fontaine's version of the fable.

The Frogs Who Desired a King is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 44 in the Perry Index. Throughout its history, the story has been given a political application.

The Dog and Its Reflection is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 133 in the Perry Index. The Greek language original was retold in Latin and in this way was spread across Europe, teaching the lesson to be contented with what one has and not to relinquish substance for shadow. There also exist Indian variants of the story. The morals at the end of the fable have provided both English and French with proverbs and the story has been applied to a variety of social situations.

Still waters run deep is a proverb of Latin origin now commonly taken to mean that a placid exterior hides a passionate or subtle nature. Formerly it also carried the warning that silent people are dangerous, as in Suffolk's comment on a fellow lord in William Shakespeare's play Henry VI part 2:

The drowned woman and her husband is a story found in Mediaeval jest-books that entered the fable tradition in the 16th century. It was occasionally included in collections of Aesop's Fables but never became established as such and has no number in the Perry Index. Folk variants in which a contrary wife is sought upstream by her husband after she drowns are catalogued under the Aarne-Thompson classification system as type 1365A.

The Man with Two Mistresses is one of Aesop's Fables that deals directly with human foibles. It is numbered 31 in the Perry Index.

The Fox and the Weasel is a title used to cover a complex of fables in which a number of other animals figure in a story with the same basic situation involving the unfortunate effects of greed. Of Greek origin, it is counted as one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 24 in the Perry Index.

The Fox and the Woodman is a cautionary story against hypocrisy included among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 22 in the Perry Index. Although the same basic plot recurs, different versions have included a variety of participants.

"The Astrologer who Fell into a Well" is a fable based on a Greek anecdote concerning the pre-Socratic philosopher Thales of Miletus. It was one of several ancient jokes that were absorbed into Aesop's Fables and is now numbered 40 in the Perry Index. During the scientific attack on astrology in the 16th–17th centuries, the story again became very popular.

The Ass and his Masters is a fable that has also gone by the alternative titles The ass and the gardener and Jupiter and the ass. Included among Aesop's Fables, it is numbered 179 in the Perry Index.

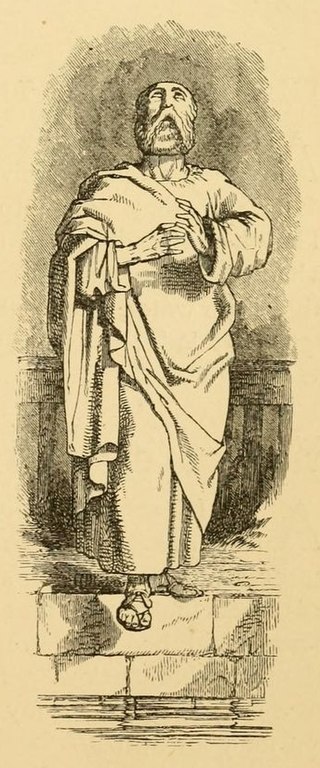

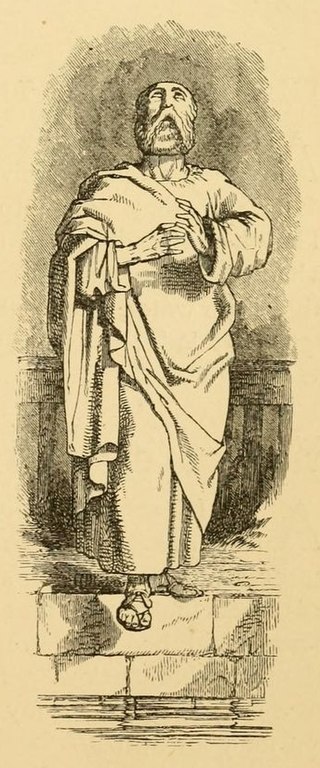

The Old Man and Death is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 60 in the Perry Index. Because this was one of the comparatively rare fables featuring humans, it was the subject of many paintings, especially in France, where Jean de la Fontaine's adaptation had made it popular.

The Ass Carrying an Image is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 182 in the Perry Index. It is directed against human conceit but at one period was also used to illustrate the argument in Canon Law that the sacramental act is not diminished by the priest's unworthiness.

The Farmer and his Sons is a story of Greek origin that is included among Aesop's Fables and is listed as 42 in the Perry Index. It illustrates both the value of hard work and the need to temper parental advice with practicality.

There are five fables of ancient Greek origin that deal with the statue of Hermes. All have been classed as burlesques that show disrespect to the god involved and some scepticism concerning the efficacy of religious statues as objects of worship. Statues of Hermes differed according to function and several are referenced in these stories. Only one fable became generally retold in later times, although two others also achieved some currency.

The Fly and the Ant is one of Aesop's Fables that appears in the form of a debate between the two insects. It is numbered 521 in the Perry Index.