Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of diverse origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

A wolf in sheep's clothing is an idiom of Biblical origin used to describe those playing a role contrary to their real character with whom contact is dangerous, particularly false teachers. Much later, the idiom has been applied by zoologists to varying kinds of predatory behaviour. A fable based on it has been falsely credited to Aesop and is now numbered 451 in the Perry Index. The confusion has arisen from the similarity of the theme with fables of Aesop concerning wolves that are mistakenly trusted by shepherds; the moral drawn from these is that one's basic nature eventually shows through the disguise.

Zeus and the Tortoise appears among Aesop’s Fables and explains how the tortoise got her shell. It is numbered 106 in the Perry Index. From it derives the proverbial sentiment that ‘There’s no place like home’.

The Wolf and the Lamb is a well-known fable of Aesop and is numbered 155 in the Perry Index. There are several variant stories of tyrannical injustice in which a victim is falsely accused and killed despite a reasonable defence.

The Walnut Tree is one of Aesop's fables and numbered 250 in the Perry Index. It later served as a base for a misogynistic proverb, which encourages the violence against walnut trees, asses and women.

The Hawk and the Nightingale is one of the earliest fables recorded in Greek and there have been many variations on the story since Classical times. The original version is numbered 4 in the Perry Index and the later Aesop version, sometimes going under the title "The Hawk, the Nightingale and the Birdcatcher", is numbered 567. The stories began as a reflection on the arbitrary use of power and eventually shifted to being a lesson in the wise use of resources.

The Two Pots is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 378 in the Perry Index. The fable may stem from proverbial sources.

The Fox and the Lion is one of Aesop's Fables and represents a comedy of manners. It is number 10 in the Perry Index.

Speaking of The Snake and the Crab in Ancient Greece was the equivalent of the modern idiom, 'Pot calling the kettle black'. A fable attributed to Aesop was eventually created about the two creatures and later still yet another fable concerning a crab and its offspring was developed to make the same point.

The Crow or Raven and the Snake or Serpent is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 128 in the Perry Index. Alternative Greek versions exist and two of these were adopted during the European Renaissance. The fable is not to be confused with the story of this title in the Panchatantra, which is completely different.

The Dog and the Wolf is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 346 in the Perry Index. It has been popular since antiquity as an object lesson of how freedom should not be exchanged for comfort or financial gain. An alternative fable with the same moral concerning different animals is less well known.

The Fox and the Woodman is a cautionary story against hypocrisy included among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 22 in the Perry Index. Although the same basic plot recurs, different versions have included a variety of participants.

The cautionary tale of The Mouse and the Oyster is rarely mentioned in Classical literature but is counted as one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 454 in the Perry Index. It has been variously interpreted, either as a warning against gluttony or as a caution against unwary behaviour.

Developed by authors during Renaissance times, the story of an ass eating thistles was a late addition to collections of Aesop's Fables. Beginning as a condemnation of miserly behaviour, it eventually was taken to demonstrate how preferences differ.

The Ass Carrying an Image is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 182 in the Perry Index. It is directed against human conceit but at one period was also used to illustrate the argument in Canon Law that the sacramental act is not diminished by the priest's unworthiness.

Hercules and the Wagoner or Hercules and the Carter is a fable credited to Aesop. It is associated with the proverb "God helps those who help themselves", variations on which are found in other ancient Greek authors.

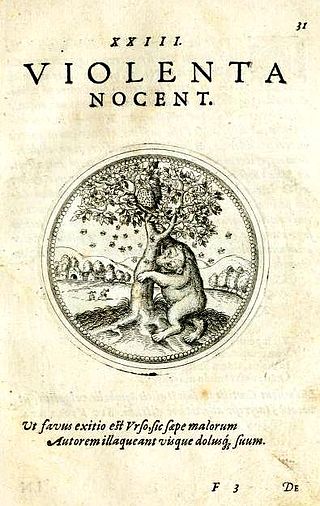

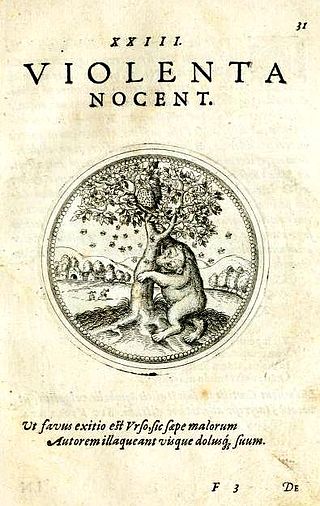

The Bear and the Bees is a fable of North Italian origin that became popular in other countries between the 16th - 19th centuries. There it has often been ascribed to Aesop's fables, although there is no evidence for this and it does not appear in the Perry Index. Various versions have been given different interpretations over time and artistic representations have been common.

The Old Woman and the Wine Jar is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 493 in the Perry Index. It has been applied to situations where an influence for good is lasting, such as the effect of education.

The story of the feud between the eagle and the beetle is one of Aesop's Fables and often referred to in Classical times. It is numbered 3 in the Perry Index and the episode became proverbial. Although different in detail, it can be compared to the fable of The Eagle and the Fox. In both cases the eagle believes itself safe from retribution for an act of violence and is punished by the destruction of its young.

The Oxen and the Creaking Cart is a situational fable ascribed to Aesop and is numbered 45 in the Perry Index. Originally directed against complainers, it was later linked with the proverb ‘the worst wheel always creaks most’ and aimed emblematically at babblers of all sorts.