Volusia County is a county located in the east-central part of the U.S. state of Florida between the St. Johns River and the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2020 census, the county was home to 553,543 people, an increase of 11.9% from the 2010 census. It was founded on December 29, 1854, from part of Orange County, and was named for the community of Volusia, located in northwestern Volusia County. Its first county seat was Enterprise. Since 1887, its county seat has been DeLand.

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups of people collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of American Indians and Black Indians. It was part of a series of conflicts called the Seminole Wars. The Second Seminole War, often referred to as the Seminole War, is regarded as "the longest and most costly of the Indian conflicts of the United States". After the Treaty of Payne's Landing in 1832 that called for the Seminole's removal from Florida, tensions rose until fierce hostilities occurred in the Dade battle in 1835. This conflict started the war. The Seminoles and the U.S. forces engaged in mostly small engagements for more than six years. By 1842, only a few hundred native peoples remained in Florida. Although no peace treaty was ever signed, the war was declared over on August 14, 1842.

De Leon Springs State Park is a Florida State Park in Volusia County, Florida. It is located in DeLeon Springs, off CR 3.

Joseph Marion Hernández was a slave-owning American planter, politician and military officer. He was the first delegate from the Florida Territory and the first Hispanic American to serve in the United States Congress. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he served from September 1822 to March 1823.

The Battle of Wahoo Swamp was an extended military engagement of the Second Seminole War fought in November 1836 in the Wahoo Swamp, approximately 50 miles northeast of Fort Brooke in Tampa and 35 miles south of Fort King in Ocala in modern Sumter County, Florida. General Richard K. Call, the territorial governor of Florida, led a mixed force consisting of Florida militia, Tennessee volunteers, Creek mercenaries, and some troops of the US Army and Marines against Seminole forces led by chiefs Osuchee and Yaholooche.

Bulow Plantation Ruins Historic State Park is a Florida State Park in Flagler Beach, Florida. It is three miles west of Flagler Beach on CR 2001, south of SR 100, and contains the ruins of an ante-bellum plantation and its sugar mill, built of coquina, a fossiliferous sedimentary rock composed of shells. It was the largest plantation in East Florida, and was operated with the forced labor of enslaved Africans and African Americans.

Mosquito County is the historic name of an early county that once comprised most of the eastern part of Florida. Its land included all of present-day Volusia, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, Seminole, Osceola, Orange, Lake, Polk and Palm Beach counties.

The New Smyrna Sugar Mill Ruins is a historic site in New Smyrna Beach, Florida, at 600 Old Mission Road, one mile west of the Intracoastal Waterway. On August 12, 1970, it was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

Ximenez-Fatio House Museum is one of the best-preserved and most authentic Second Spanish Period (1783-1821) residential buildings in St. Augustine, Florida. In 1973, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. It was designated a Florida Heritage Landmark in 2012.

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek, also known as the Treaty with the Florida Tribes of Indians, was an agreement signed in 1823 between the government of the United States and the chiefs of several groups and bands of Indians living in the present-day state of Florida. The treaty established a reservation in the center of the Florida peninsula. It also ceded all coastal lands to the United States Government, as the U.S. wanted control of overseas trade between the Florida and the Caribbean.

Douglas Dummett (1806–1873) was an American planter, plantation owner, and politician. He served as a member of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida representing St. Johns County in 1843, and a member of the Florida House of Representatives representing Mosquito County in 1845. He was instrumental in developing the Indian River Citrus industry in Florida.

Ee-mat-la, also known as King Phillip, was a Seminole chief during the Second Seminole War.

Uchee Billy or Yuchi Billy was a chief of a Yuchi band in Florida during the first half of the 19th century. Uchee Billy's band was living near Lake Miccosukee when Andrew Jackson invaded Spanish Florida during the First Seminole War and attacked the villages in the area. Yuchi Billy and his band then moved to the St. Johns River. During the Second Seminole War, Uchee Billy was an ally of the Seminoles, and was one of the principal war chiefs who fought the U.S. Army.

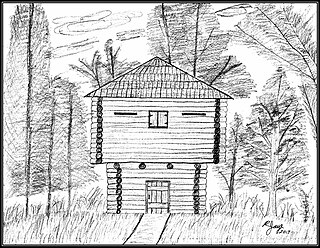

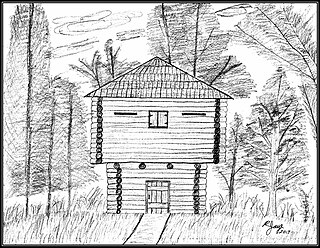

Fort Peyton was a stockaded fort built in August 1837 by the United States Army, one of a chain of military outposts created during the Second Seminole War for the protection of the St. Augustine area in Florida Territory. Established by Maj. Gen. Thomas Jesup, it was garrisoned by regular army troops.

Fort Caben was a Second Seminole War fort in Flagler County, Florida. In 1958, a report listing Flagler County historical sites, compiled for Florida Governor Thomas LeRoy Collins (1909–1991) and the State Park Board, stated, "'Fort Caben' was built for defense against the Indians – about 1834. No trace left. [It was] probably a wood building. Location: Section 38, Township 13 – South, Range 29 East, on Fish Hawk Point."

Fort Fulton was established on February 21, 1840, between Old Kings Road and Pellicer Creek in present-day Flagler County, Florida. A January 17, 1840 article in the Florida Herald of St. Augustine stated, "Can anyone inform us why the Mounted Volunteer Company, raised in this city, and now stationed at Hewlett’s [Hewitt’s] Mill, is weakened by a detail of ten men subject to the order of the city council, and kept in town idle." This article suggests that Fort Fulton was most likely manned with militia volunteers since it was the only military post in the general area of Hewitt's Mill. Hewitt's Mill was a sawmill built in 1768 by John Hewitt on his 1,000-acre plot of land in St. Johns County. This sawmill is known to have supplied many wooden building materials to the St. Augustine area and surrounding plantations.

The St. Joseph's Plantation was established in 1816 during the Second Spanish Rule (1783–1821) of Florida after Joseph Marion Hernandez purchased an 807.5-acre Spanish land grant. The forced-labor farm was located near the present-day intersection of Palm Coast Parkway and Old Kings Road in Palm Coast, Flagler County, Florida.

The Mosquito Roarers was an American militia company formed in Mosquito County, Florida. Called into service during the Fall of 1835, the militia became Company B of the Florida militia. They were involved in battles against the Seminole people.

Gad Humphreys was an officer in the United States Army and an Indian agent in Florida. He was appointed to his post in 1822. He was supportive of the Indians and tried to help them and protect them from encroachments by White settlers. He was accused of abusing his post by preventing or delaying the return to their owners of fugitive slaves that had taken refuge with the Indians. An investigation was conducted, but none of his accusers were willing to testify. Even so, he was removed from his post in 1830.