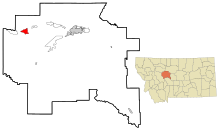

Hays is a census-designated place (CDP) in Blaine County, Montana, United States. The population was 843 at the 2010 census. The community lies within the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, near the reservation's southern end. The nearby community of Lodge Pole lies to the east.

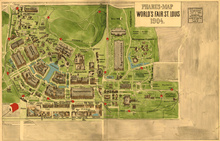

The 1904 Summer Olympics were an international multi-sport event held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from 29 August to 3 September 1904, as part of an extended sports program lasting from 1 July to 23 November 1904, located at what is now known as Francis Field on the campus of Washington University in St. Louis. This was the first time that the Olympic Games were held outside Europe.

Women's basketball is the team sport of basketball played by women. It began being played in 1892, one year after men's basketball, at Smith College in Massachusetts. It spread across the United States, in large part via women's college competitions, and has since spread globally. As of 2020, basketball is one of the most popular and fastest growing sports in the world.

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people, also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota, are a First Nations/Native American people originally from the Northern Great Plains of North America.

Nakota is the endonym used by those native peoples of North America who usually go by the name of Assiniboine, in the United States, and of Stoney, in Canada.

The Gros Ventre, also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in northcentral Montana. Today, the Gros Ventre people are enrolled in the Fort Belknap Indian Community of the Fort Belknap Reservation of Montana, a federally recognized tribe with 7,000 members, also including the Assiniboine people.

Fort Peck Community College (FPCC) is a public tribal land-grant community college in Poplar, Montana. The college is located on the Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Reservation in the northeast corner of Montana, which encompasses over two million acres. The college also has a satellite campus in Wolf Point.

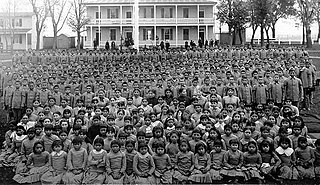

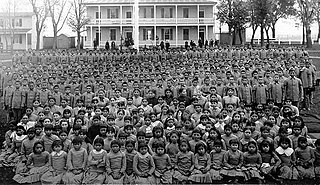

The United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, generally known as Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. It took over the historic Carlisle Barracks, which was transferred to the Department of Interior from the War Department. After the United States entry into World War I, the school was closed and this property was transferred back to the Department of Defense. All the property is now part of the U.S. Army War College.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was signed on September 17, 1851 between United States treaty commissioners and representatives of the Cheyenne, Sioux, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nations. Also known as Horse Creek Treaty, the treaty set forth traditional territorial claims of the tribes.

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation is the federally recognized Northern Cheyenne tribe. Located in southeastern Montana, the reservation is approximately 690 square miles (1,800 km2) in size and home to approximately 6,000 Cheyenne people. The tribal and government headquarters are located in Lame Deer, also the home of the annual Northern Cheyenne pow wow.

The Fort Peck Indian Reservation is located near Fort Peck, Montana, in the northeast part of the state. It is the home of several federally recognized bands of Assiniboine, Nakota, Lakota, and Dakota peoples of Native Americans.

The Fort Belknap Indian Reservation is shared by two Native American tribes, the A'aninin and the Nakoda (Assiniboine). The reservation covers 1,014 sq mi (2,630 km2), and is located in north-central Montana. The total area includes the main portion of their homeland and off-reservation trust land. The tribes reported 2,851 enrolled members in 2010. The capital and largest community is Fort Belknap Agency, at the reservation's north end, just south of the city of Harlem, Montana, across the Milk River.

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Native American children and youth into European American culture. In the process, these schools denigrated Native American culture and made children give up their languages and religion. At the same time the schools provided a basic Western education. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations. The missionaries were often approved by the federal government to start both missions and schools on reservations, especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries especially, the government paid religious orders to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations, and later established its own schools on reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also founded additional off-reservation boarding schools based on the assimilation model. These sometimes drew children from a variety of tribes. In addition, religious orders established off-reservation schools.

Fort Shaw was a United States Army fort located on the Sun River 24 miles west of Great Falls, Montana, in the United States. It was founded on June 30, 1867, and abandoned by the Army in July 1891. It later served as a school for Native American children from 1892 to 1910. Portions of the fort survive today as a small museum. The fort lent its name to the community of Fort Shaw, Montana, which grew up around it.

The St. Peter's Mission Church and Cemetery, also known as St. Peter's Mission and as St. Peter's-By-the-Rock is a historic Roman Catholic mission located on Mission Road 10.5 miles (16.9 km) west-northwest of the town of Cascade, Montana, United States. The historic site consists of a wooden church and "opera house" and a cemetery. Also on the site are the ruins of a stone parochial school for boys, a stone convent, and several outbuildings.

Herman Peter Hauser was a United States Native American football player. He played for the Haskell Indians football team from 1904 to 1905 and for the Carlisle Indians football team from 1906 to 1910 and was selected as a consensus first-team fullback on the 1907 College Football All-America Team. He was a multi-talented player who ran with the ball, handled place-kicking and punt returns, and has been credited as the first player in American football to throw a spiral pass.

The Olympic Games have been criticized as upholding the colonial policies and practices of some host nations and cities either in the name of the Olympics by associated parties or directly by official Olympic bodies, such as the International Olympic Committee, host organizing committees and official sponsors.

Dolly Akers was an Assiniboine woman who was the first Native American woman elected to the Montana Legislature with 100% of the Indian vote and the first woman elected to the Tribal Executive Board of the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation.

Gilbert Horn Sr. was an American military veteran who served as an Assiniboine code talker during World War II. Horn, a member of the Merrill's Marauders during the war, utilized the Assiniboine language to encode communications by the U.S. military in the Pacific theater. In 2014, Horn was named an honorary chief by the Fort Belknap Assiniboine Tribe, becoming the first person to be awarded the title since the 1890s.

William Standing, also known as Fire Bear was an American painter and illustrator. He was Assiniboine, and his work depicted the lives of Native Americans in the Northwestern United States.