The Antigonid dynasty was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the kingdom of Macedon during the Hellenistic period. Founded by Antigonus I Monophthalmus, a general and successor of Alexander the Great, the dynasty first came to power after the Battle of Salamis in 306 BC and ruled much of Hellenistic Greece from 294 until their defeat at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC, after which Macedon came under the control of the Roman Republic.

Year 306 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Tremulus and Arvina. The denomination 306 BC for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Nicomedes I, second king of Bithynia, was the eldest son of Zipoetes I, whom he succeeded on the throne in 278 BC.

Demetrius I Poliorcetes was a Macedonian Greek nobleman and military leader who became king of Asia between 306 and 301 BC, and king of Macedon between 294 and 288 BC. A member of the Antigonid dynasty, he was the son of its founder, Antigonus I Monophthalmus, and his wife Stratonice, as well as the first member of the family to rule Macedon in Hellenistic Greece.

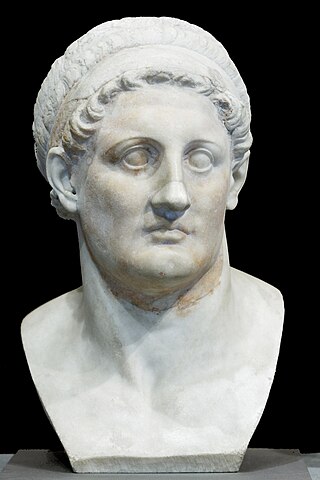

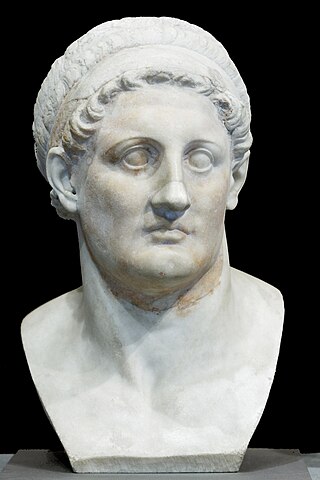

Ptolemy I Soter was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Ptolemy was basileus and pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt from 305/304 BC to his death in 282 BC, and his descendants continued to rule Egypt until 30 BC. During their rule, Egypt became a thriving bastion of Hellenistic civilization and Alexandria a great seat of Greek culture.

Antigonus I Monophthalmus was a Macedonian Greek general and successor of Alexander the Great. A prominent military leader in Alexander's army, he went on to control large parts of Alexander's former empire. He assumed the title of basileus (king) in 306 BC and reigned until his death. He was the founder of the Antigonid dynasty, which ruled over Macedonia until its conquest by the Roman Republic in 168 BC.

Pyrrhus was a Greek king and statesman of the Hellenistic period. He was king of the Molossians, of the royal Aeacid house, and later he became king of Epirus. He was one of the strongest opponents of early Rome, and had been regarded as one of the greatest generals of antiquity. Several of his victorious battles caused him unacceptably heavy losses, from which the phrase "Pyrrhic victory" was coined.

Lysimachus was a Thessalian officer and successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became king of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

The Battle of Ipsus was fought between some of the Diadochi in 301 BC near the town of Ipsus in Phrygia. Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the Macedonian ruler of large parts of Asia, and his son Demetrius were pitted against the coalition of three other successors of Alexander: Cassander, ruler of Macedon; Lysimachus, ruler of Thrace; and Seleucus I Nicator, ruler of Babylonia and Persia.

The Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of Alexander's Successors were a series of conflicts fought between the generals of Alexander the Great, known as the Diadochi, over who would rule his empire following his death. The fighting occurred between 322 and 281 BC.

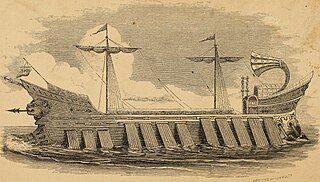

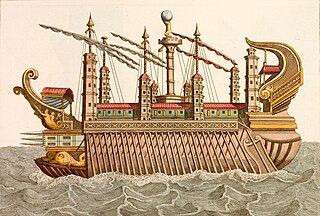

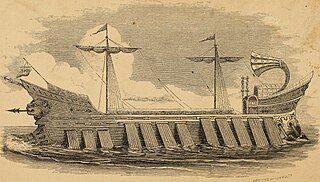

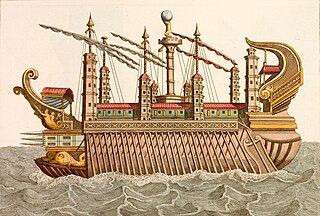

From the 4th century BC on, new types of oared warships appeared in the Mediterranean Sea, superseding the trireme and transforming naval warfare. Ships became increasingly large and heavy, including some of the largest wooden ships hitherto constructed. These developments were spearheaded in the Hellenistic Near East, but also to a large extent shared by the naval powers of the Western Mediterranean, specifically Carthage and the Roman Republic. While the wealthy successor kingdoms in the East built huge warships ("polyremes"), Carthage and Rome, in the intense naval antagonism during the Punic Wars, relied mostly on medium-sized vessels. At the same time, smaller naval powers employed an array of small and fast craft, which were also used by the ubiquitous pirates. Following the establishment of complete Roman hegemony in the Mediterranean after the Battle of Actium, the nascent Roman Empire faced no major naval threats. In the 1st century AD, the larger warships were retained only as flagships and were gradually supplanted by the light liburnians until, by Late Antiquity, the knowledge of their construction had been lost.

The naval Battle of Salamis in 306 BC took place off Salamis, Cyprus between the fleets of Ptolemy I of Egypt and Antigonus I Monophthalmus, two of the Diadochi, the generals who, after the death of Alexander the Great, fought each other for control of his empire.

Mithridates I Ctistes, also known as Mithridates III of Cius, was a Persian nobleman and the founder of the Kingdom of Pontus in Anatolia.

Ptolemaeus or Ptolemy was a nephew and general of Antigonus I Monophthalmus, one of the Successors of Alexander the Great. His father was also called Ptolemy and was a brother of Antigonus. Ptolemy, the nephew, was Antigonus's right-hand-man until his son Demetrius took on a more prominent role.

Aristodemus of Miletus was one of the oldest and most trusted friends of Antigonus Monophthalmus. He is described by Plutarch as an arch-flatterer of Antigonus. Antigonus frequently used him on important diplomatic missions and occasionally entrusted him with military commands as well.

Memnon of Heraclea was a Greek historical writer, probably a native of Heraclea Pontica. He described the history of that city in a large work, known only through the Excerpta of Photius, and describing especially the various tyrants who had at times ruled Heraclea.

Tessarakonteres, or simply "forty", was a very large catamaran galley reportedly built in the Hellenistic period by Ptolemy IV Philopator of Egypt. It was described by a number of ancient sources, including a lost work by Callixenus of Rhodes and surviving texts by Athenaeus and Plutarch. According to these descriptions, supported by modern research by Lionel Casson, the enormous size of the vessel made it impractical and it was built only as a prestige vessel, rather than an effective warship. The name "forty" refers not to the number of oars, but to the number of rowers on each column of oars that propelled it, and at the size described it would have been the largest ship constructed in antiquity, and probably the largest human-powered vessel ever built.

Syracusia was an ancient Greek ship sometimes claimed to be the largest transport ship of antiquity. She was reportedly too big for any port in Sicily, and thus only sailed once from Syracuse in Sicily to Alexandria in the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, whereupon she was given as a present to Ptolemy III Euergetes. The exact dimension of Syracusia is unknown; Michael Lahanas put it at 55 m long, 14 m wide, and 13 m high.

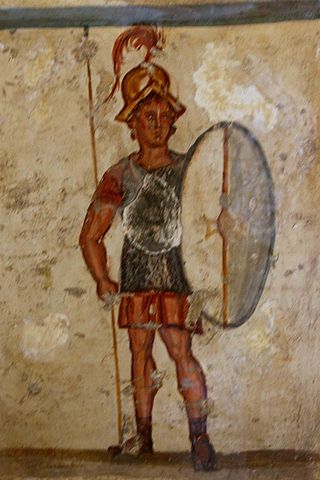

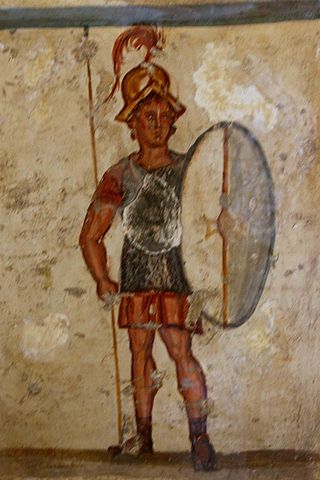

The Antigonid Macedonian army was the army that evolved from the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia in the period when it was ruled by the Antigonid dynasty from 276 BC to 168 BC. It was seen as one of the principal Hellenistic fighting forces until its ultimate defeat at Roman hands at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC. However, there was a brief resurgence in 150-148 during the revolt of Andriscus, a supposed heir to Perseus.

The Ptolemaic navy was the naval force of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and later empire from 305 to 30 BC. It was founded by King Ptolemy I. Its main naval bases were at Alexandria, Egypt and Nea Paphos in Cyprus. It operated in the East Mediterranean in the Aegean Sea, the Levantine Sea, but also on the river Nile and in the Red Sea towards the Indian Ocean.