In geography and geology, fluvial sediment processes or fluvial sediment transport are associated with rivers and streams and the deposits and landforms created by sediments. It can result in the formation of ripples and dunes, in fractal-shaped patterns of erosion, in complex patterns of natural river systems, and in the development of floodplains and the occurrence of flash floods. Sediment moved by water can be larger than sediment moved by air because water has both a higher density and viscosity. In typical rivers the largest carried sediment is of sand and gravel size, but larger floods can carry cobbles and even boulders. When the stream or rivers are associated with glaciers, ice sheets, or ice caps, the term glaciofluvial or fluvioglacial is used, as in periglacial flows and glacial lake outburst floods. Fluvial sediment processes include the motion of sediment and erosion or deposition on the river bed.

Shear stress is the component of stress coplanar with a material cross section. It arises from the shear force, the component of force vector parallel to the material cross section. Normal stress, on the other hand, arises from the force vector component perpendicular to the material cross section on which it acts.

Soil mechanics is a branch of soil physics and applied mechanics that describes the behavior of soils. It differs from fluid mechanics and solid mechanics in the sense that soils consist of a heterogeneous mixture of fluids and particles but soil may also contain organic solids and other matter. Along with rock mechanics, soil mechanics provides the theoretical basis for analysis in geotechnical engineering, a subdiscipline of civil engineering, and engineering geology, a subdiscipline of geology. Soil mechanics is used to analyze the deformations of and flow of fluids within natural and man-made structures that are supported on or made of soil, or structures that are buried in soils. Example applications are building and bridge foundations, retaining walls, dams, and buried pipeline systems. Principles of soil mechanics are also used in related disciplines such as geophysical engineering, coastal engineering, agricultural engineering, hydrology and soil physics.

Precipitation hardening, also called age hardening or particle hardening, is a heat treatment technique used to increase the yield strength of malleable materials, including most structural alloys of aluminium, magnesium, nickel, titanium, and some steels, stainless steels, and duplex stainless steel. In superalloys, it is known to cause yield strength anomaly providing excellent high-temperature strength.

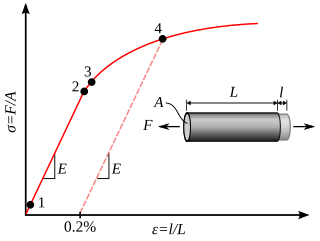

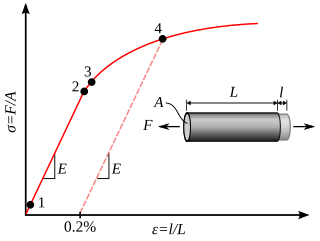

In materials science and engineering, the yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning of plastic behavior. Below the yield point, a material will deform elastically and will return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible and is known as plastic deformation.

The Exner equation is a statement of conservation of mass that applies to sediment in a fluvial system such as a river. It was developed by the Austrian meteorologist and sedimentologist Felix Maria Exner, from whom it derives its name.

Debris flows are geological phenomena in which water-laden masses of soil and fragmented rock rush down mountainsides, funnel into stream channels, entrain objects in their paths, and form thick, muddy deposits on valley floors. They generally have bulk densities comparable to those of rock avalanches and other types of landslides, but owing to widespread sediment liquefaction caused by high pore-fluid pressures, they can flow almost as fluidly as water. Debris flows descending steep channels commonly attain speeds that surpass 10 m/s (36 km/h), although some large flows can reach speeds that are much greater. Debris flows with volumes ranging up to about 100,000 cubic meters occur frequently in mountainous regions worldwide. The largest prehistoric flows have had volumes exceeding 1 billion cubic meters. As a result of their high sediment concentrations and mobility, debris flows can be very destructive.

Sediment transport is the movement of solid particles (sediment), typically due to a combination of gravity acting on the sediment, and the movement of the fluid in which the sediment is entrained. Sediment transport occurs in natural systems where the particles are clastic rocks, mud, or clay; the fluid is air, water, or ice; and the force of gravity acts to move the particles along the sloping surface on which they are resting. Sediment transport due to fluid motion occurs in rivers, oceans, lakes, seas, and other bodies of water due to currents and tides. Transport is also caused by glaciers as they flow, and on terrestrial surfaces under the influence of wind. Sediment transport due only to gravity can occur on sloping surfaces in general, including hillslopes, scarps, cliffs, and the continental shelf—continental slope boundary.

The suspended load of a flow of fluid, such as a river, is the portion of its sediment uplifted by the fluid's flow in the process of sediment transportation. It is kept suspended by the fluid's turbulence. The suspended load generally consists of smaller particles, like clay, silt, and fine sands.

Shear strength is a term used in soil mechanics to describe the magnitude of the shear stress that a soil can sustain. The shear resistance of soil is a result of friction and interlocking of particles, and possibly cementation or bonding of particle contacts. Due to interlocking, particulate material may expand or contract in volume as it is subject to shear strains. If soil expands its volume, the density of particles will decrease and the strength will decrease; in this case, the peak strength would be followed by a reduction of shear stress. The stress-strain relationship levels off when the material stops expanding or contracting, and when interparticle bonds are broken. The theoretical state at which the shear stress and density remain constant while the shear strain increases may be called the critical state, steady state, or residual strength.

In hydrology and geography, armor is the association of surface pebbles, rocks or boulders with stream beds or beaches. Most commonly hydrological armor occurs naturally; however, a man-made form is usually called riprap, when shorelines or stream banks are fortified for erosion protection with large boulders or sizable manufactured concrete objects. When armor is associated with beaches in the form of pebbles to medium-sized stones grading from two to 200 millimeters across, the resulting landform is often termed a shingle beach. Hydrological modeling indicates that stream armor typically persists in a flood stage environment.

Ice sheet dynamics describe the motion within large bodies of ice such as those currently on Greenland and Antarctica. Ice motion is dominated by the movement of glaciers, whose gravity-driven activity is controlled by two main variable factors: the temperature and the strength of their bases. A number of processes alter these two factors, resulting in cyclic surges of activity interspersed with longer periods of inactivity, on both hourly and centennial time scales. Ice-sheet dynamics are of interest in modelling future sea level rise.

Shear velocity, also called friction velocity, is a form by which a shear stress may be re-written in units of velocity. It is useful as a method in fluid mechanics to compare true velocities, such as the velocity of a flow in a stream, to a velocity that relates shear between layers of flow.

Stream power, originally derived by R. A. Bagnold in the 1960s, is the amount of energy the water in a river or stream is exerting on the sides and bottom of the river. Stream power is the result of multiplying the density of the water, the acceleration of the water due to gravity, the volume of water flowing through the river, and the slope of that water. There are many forms of the stream power formula with varying utilities, such as comparing rivers of various widths or quantifying the energy required to move sediment of a certain size. Stream power is closely related to other criteria such as stream competency and shear stress. Stream power is a valuable measurement for hydrologists and geomorphologists tackling sediment transport issues as well as for civil engineers, who use it in the planning and construction of roads, bridges, dams, and culverts.

Three components that are included in the load of a river system are the following: dissolved load, wash load and bed material load. The bed material load is the portion of the sediment that is transported by a stream that contains material derived from the bed. Bed material load typically consists of all of the bed load, and the proportion of the suspended load that is represented in the bed sediments. It generally consists of grains coarser than 0.062 mm with the principal source being the channel bed. Its importance lies in that its composition is that of the bed, and the material in transport can therefore be actively interchanged with the bed. For this reason, bed material load exerts a control on river channel morphology. Bed load and wash load together constitute the total load of sediment in a stream. The order in which the three components of load have been considered – dissolved, wash, bed material – can be thought of as progression: of increasingly slower transport velocities, so that the load peak lags further and further behind the flow peak during any event.

A bedrock river is a river that has little to no alluvium mantling the bedrock over which it flows. However, most bedrock rivers are not pure forms; they are a combination of a bedrock channel and an alluvial channel. The way one can distinguish between bedrock rivers and alluvial rivers is through the extent of sediment cover.

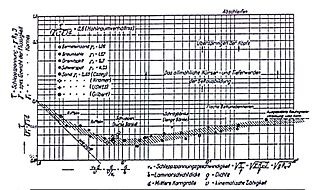

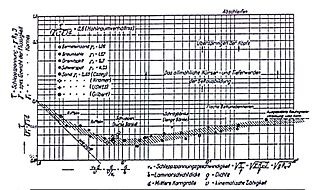

The Shields parameter, also called the Shields criterion or Shields number, is a nondimensional number used to calculate the initiation of motion of sediment in a fluid flow. It is a nondimensionalization of a shear stress, and is typically denoted or . This parameter has been developed by Albert F. Shields, and is called later Shields parameter. The Shields parameter is the main parameter of the Shields formula. It is given by:

In hydrology stream competency, also known as stream competence, is a measure of the maximum size of particles a stream can transport. The particles are made up of grain sizes ranging from large to small and include boulders, rocks, pebbles, sand, silt, and clay. These particles make up the bed load of the stream. Stream competence was originally simplified by the “sixth-power-law,” which states the mass of a particle that can be moved is proportional to the velocity of the river raised to the sixth power. This refers to the stream bed velocity which is difficult to measure or estimate due to the many factors that cause slight variances in stream velocities.

Erodability is the inherent yielding or nonresistance of soils and rocks to erosion. A high erodability implies that the same amount of work exerted by the erosion processes leads to a larger removal of material. Because the mechanics behind erosion depend upon the competence and coherence of the material, erodability is treated in different ways depending on the type of surface that eroded.

The Shields formula is a formula for the stability calculation of granular material in running water.