Deism is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation of the natural world are exclusively logical, reliable, and sufficient to determine the existence of a Supreme Being as the creator of the universe. More simply stated, Deism is the belief in the existence of God, solely based on rational thought without any reliance on revealed religions or religious authority. Deism emphasizes the concept of natural theology—that is, God's existence is revealed through nature.

In religion and theology, revelation is the disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity (god) or other supernatural entity or entities.

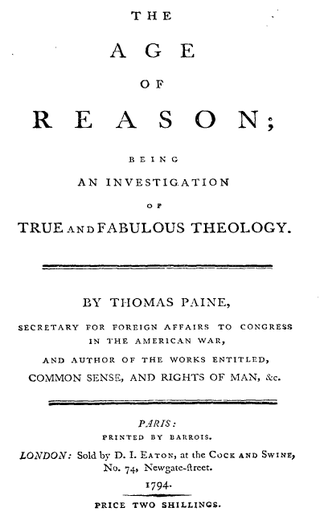

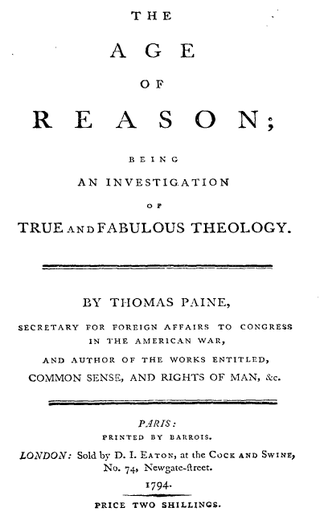

The Age of Reason; Being an Investigation of True and Fabulous Theology is a work by English and American political activist Thomas Paine, arguing for the philosophical position of deism. It follows in the tradition of 18th-century British deism, and challenges institutionalized religion and the legitimacy of the Bible. It was published in three parts in 1794, 1795, and 1807.

Matthew Tindal was an eminent English deist author. His works, highly influential at the dawn of the Enlightenment, caused great controversy and challenged the Christian consensus of his time.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Christian theology:

Cultural Christians are the nonreligious or non-practicing Christians who received Christian values and appreciate Christian culture. As such, these individuals usually identify themselves as culturally Christians, and are often seen by practicing believers as nominal Christians. This kind of identification may be due to various factors, such as family background, personal experiences, and the social and cultural environment in which they grew up.

Liberal Christianity, also known as liberal theology and historically as Christian Modernism, is a movement that interprets Christian teaching by taking into consideration modern knowledge, science and ethics. It emphasizes the importance of reason and experience over doctrinal authority. Liberal Christians view their theology as an alternative to both atheistic rationalism and theologies based on traditional interpretations of external authority, such as the Bible or sacred tradition.

A personal god, or personal goddess, is a deity who can be related to as a person, instead of as an impersonal force, such as the Absolute. In the scriptures of the Abrahamic religions, God is described as being a personal creator, speaking in the first person and showing emotion such as anger and pride, and sometimes appearing in anthropomorphic shape. In the Pentateuch, for example, God talks with and instructs his prophets and is conceived as possessing volition, emotions, intention, and other attributes characteristic of a human person. Personal relationships with God may be described in the same ways as human relationships, such as a Father, as in Christianity, or a Friend as in Sufism.

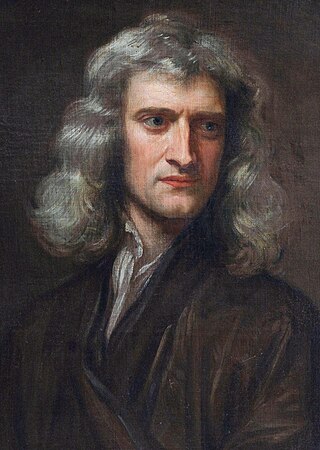

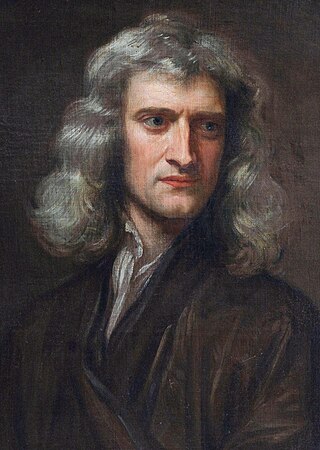

Isaac Newton was considered an insightful and erudite theologian by his Protestant contemporaries. He wrote many works that would now be classified as occult studies, and he wrote religious tracts that dealt with the literal interpretation of the Bible. He kept his heretical beliefs private.

Deistic evolution is a position in the origins debate which involves accepting the scientific evidence for evolution and age of the universe whilst advocating the view that a Deistic God created the universe but has not interfered since. The position is a counterpoint to theistic evolution and is endorsed by those who believe in Deism, and accept the scientific consensus on evolution. Various views on Deistic evolution:

The religious views of Thomas Jefferson diverged widely from the traditional Christianity of his era. Throughout his life, Jefferson was intensely interested in theology, religious studies, and morality. Jefferson was most comfortable with Deism, rational religion, theistic rationalism, and Unitarianism. He was sympathetic to and in general agreement with the moral precepts of Christianity. He considered the teachings of Jesus as having "the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man," yet he held that the pure teachings of Jesus appeared to have been appropriated by some of Jesus' early followers, resulting in a Bible that contained both "diamonds" of wisdom and the "dung" of ancient political agendas.

Atheism, as defined by the entry in Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, is "the opinion of those who deny the existence of a God in the world. The simple ignorance of God doesn't constitute atheism. To be charged with the odious title of atheism one must have the notion of God and reject it." In the period of the Enlightenment, avowed and open atheism was made possible by the advance of religious toleration, but was also far from encouraged.

Christian deism is a standpoint in the philosophy of religion stemming from Christianity and Deism. It refers to Deists who believe in the moral teachings—but not the divinity—of Jesus. Corbett and Corbett (1999) cite John Adams and Thomas Jefferson as exemplars.

Deism, the religious attitude typical of the Enlightenment, especially in France and England, holds that the only way the existence of God can be proven is to combine the application of reason with observation of the world. A Deist is defined as "One who believes in the existence of a God or Supreme Being but denies revealed religion, basing his belief on the light of nature and reason." Deism was often synonymous with so-called natural religion because its principles are drawn from nature and human reasoning. In contrast to Deism there are many cultural religions or revealed religions, such as Judaism, Trinitarian Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and others, which believe in supernatural intervention of God in the world; while Deism denies any supernatural intervention and emphasizes that the world is operated by natural laws of the Supreme Being.

The religious thought of Edmund Burke includes published works by Edmund Burke and commentary on the same. Burke's religious thought was grounded in his belief that religion is the foundation of civil society. He sharply criticized deism and atheism and emphasized Christianity as a vehicle of social progress. Born in Ireland to a Protestant father and Catholic mother, Burke vigorously defended the Church of England, but also demonstrated sensitivity to Catholic concerns. He linked the conservation of a state religion with the preservation of citizens’ constitutional liberties and highlighted Christianity’s benefits not only to the believer’s soul but also to political arrangements.

Although biological evolution has been vocally opposed by some religious groups, many other groups accept the scientific position, sometimes with additions to allow for theological considerations. The positions of such groups are described by terms including "theistic evolution", "theistic evolutionism" or "evolutionary creation". Of all the religious groups included on the chart, Buddhists are the most accepting of evolution. Theistic evolutionists believe that there is a God, that God is the creator of the material universe and all life within, and that biological evolution is a natural process within that creation. Evolution, according to this view, is simply a tool that God employed to develop human life. According to the American Scientific Affiliation, a Christian organization of scientists:

A theory of theistic evolution (TE) — also called evolutionary creation — proposes that God's method of creation was to cleverly design a universe in which everything would naturally evolve. Usually the "evolution" in "theistic evolution" means Total Evolution — astronomical evolution and geological evolution plus chemical evolution and biological evolution — but it can refer only to biological evolution.

A number of Christian writers have examined the concept of pandeism, and these have generally found it to be inconsistent with core principles of Christianity. The Roman Catholic Church, for example, condemned the Periphyseon of John Scotus Eriugena, later identified by physicist and philosopher Max Bernhard Weinstein as presenting a pandeistic theology, as appearing to obscure the separation of God and creation. The Church similarly condemned elements of the thought of Giordano Bruno which Weinstein and others determined to be pandeistic.

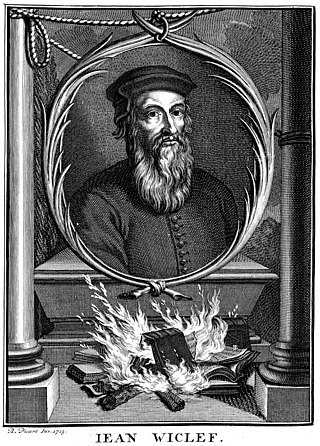

Proto-Protestantism, also called pre-Protestantism, refers to individuals and movements that propagated various ideas later associated with Protestantism before 1517, which historians usually regard as the starting year for the Reformation era. The relationship between medieval sects and Protestantism is an issue that has been debated by historians.